The cravat rose in popularity during an an age when cleaning dirty linen and ironing clothes presented an enormous challenge. Influenced by Beau Brummell’s penchant for wearing simple clothes and snowy- white cravats, these intricately-tied neckcloths became all the rage among the gentleman of the upper crust. The lower classes, for lack of servants and resources, wore a simpler version of the neckcloth in the form of a square folded and tied around the neck.

Men’s neckcloths hark back to ancient traditions in Egypt, China, and Rome where these pieces of cloth denoted a man’s social status. During the Elizabethan period a high ruffed neckline forced a stiff posture and confined movement, which only the leisure class could afford to adopt. Servants, tradesmen and laborers had to wear more functional clothing in order to perform their duties. During the mid-17th century the French adopted the fashion of neckerchiefs after seeing Croatian mercenaries wear them. The French courtiers began sporting neckcloths made of muslins or silk and decorated with lace or embroidery. These soft cloths were wrapped around the throat and loosely tied in front.

The cravat as seen in Regency portraits attained its distinctive appearance under Beau Brummell’s expert fingers and experimentation with his valet. Brummell’s philosopy of simple menswear was in stark contrast to the dandified Macaroni who pranced about in wigs, lace, and embroidered waistcoats. In Beau Brummell, His Life and Letters (p 50), Louis Melville writes:

“Brummell’s greates triumph was his neck-cloth. The neck-cloth was then a huge clinging wrap worn without stiffening of any kind and so bagging out in front. Brummell in a moment of inspiration decided to have his starched. The conception was, indeed, a stroke of genius. But genius in this case had to be backed by infinite pains. What labour must Brummell and his valet, Robinson – himself a character – have expended on experiment to discover the exact amount of stiffening that would produce the best result, and how many hours for how many days must they have worked together – in pivate – before disclosing the invention to the world of fashion. Even later, most morning could Robinson be seen coming out of the Beau’s dressing room with masses of rumpled linen on his arms – “Our failures” – he would say to the assembled company in the outer room.

Regency dandies who wore enormous cravats that prevented movement of their necks – similar to the effect Elizabethan ruffs had – were known as les incroyables or the “incredibles”. Can you spot them in the contemporary cartoon below? To learn about the social implication of extreme fashion in pre-Napoleonic France, click on this link and read Les Incroyables et Merveilleusses: Fashions as Anti-Rebellion.

- Regency Reproductions: Scroll down to read about neck cloths. Includes a free cravat pattern and illustrations of how to tie a neckcloth.

- Colonial Gentleman’s clothing: Glossary of Terms

- Francis Morris, “An Eighteenth Century Rabat”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Feb., 1927), pp. 51-55 (article consists of 5 pages)

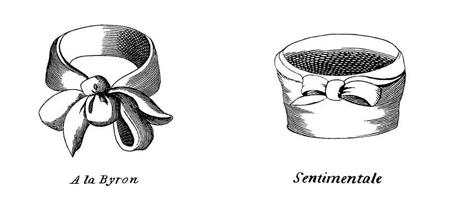

Middle illustration from H. Le Blanc’s The Art of Tying the Cravat.