By Brenda S. Cox

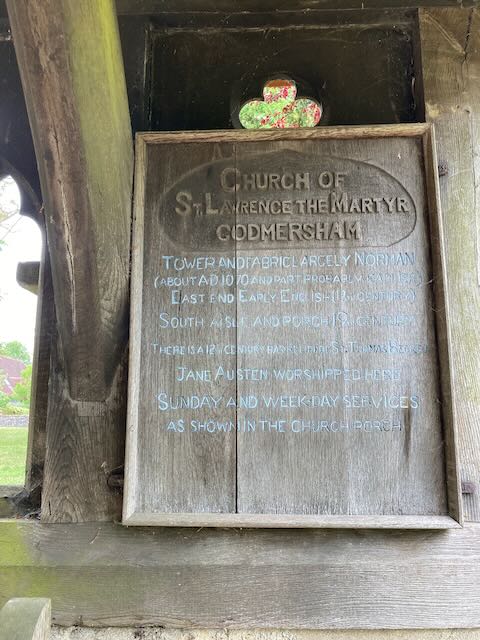

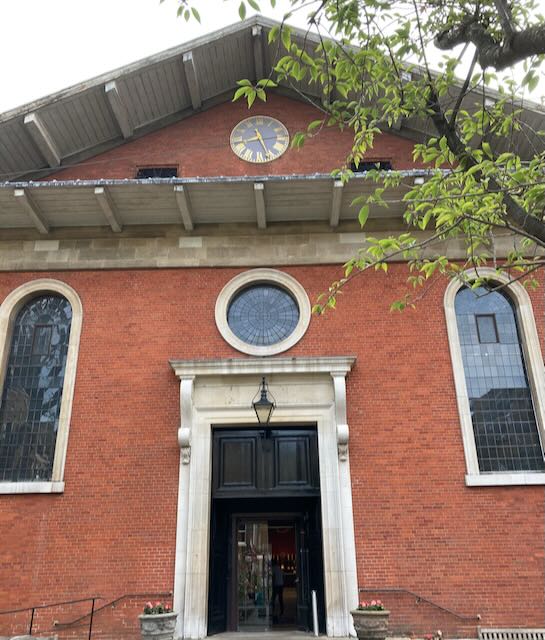

A few days ago we “visited” Godmersham, the estate of Jane Austen’s brother in Kent. Today we’ll continue that visit with the church she attended while she was there. Like so many English churches, it is named after a Christian saint.

St. Lawrence the Martyr: Who Was He?

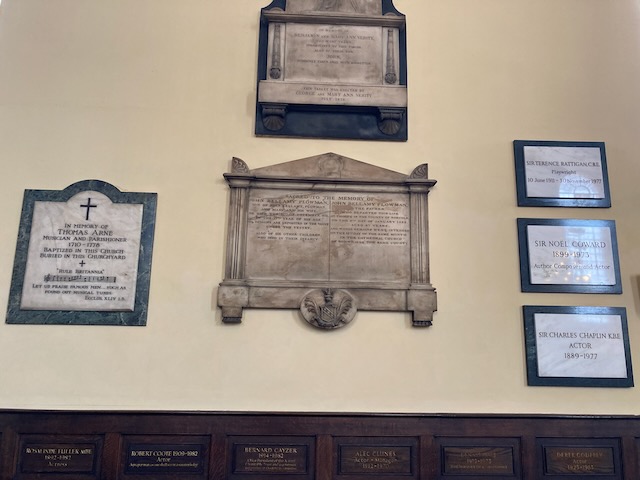

More than 200 churches in England are named after St. Lawrence. The church at Godmersham, where Jane Austen often visited her brother Edward, is one of them, as is the church at Alton, closest town to Austen’s village of Chawton.

The original St. Lawrence’s story is inspiring but rather grisly. He was a deacon in charge of the treasures of the church, and of distributing alms to the poor. When the Roman Emperor Valerian demanded that Christians sacrifice to the Roman gods or else be killed, they refused. Pope Sixtus II and his deacons were beheaded. Lawrence was told to hand over the church’s treasures. Instead of bringing gold, he brought in many of the poor and said they were the church’s treasure.

Valerian supposedly commanded that Lawrence be roasted on a gridiron, and Lawrence even made a joke as he was dying. (Some think he was actually beheaded and the gridiron is a transcription error; scroll down at this link.) He became the patron saint of comedians and poor people as well as those who work with open fires, such as bakers, and those who fear fires, such as librarians.

And, guess what else? He’s apparently the patron saint of barbecues. On August 10, St. Lawrence’s Day in the church calendar, many churches like this one celebrate by having a community-wide barbecue. Okay, that’s the grisly part. Moving on . . .

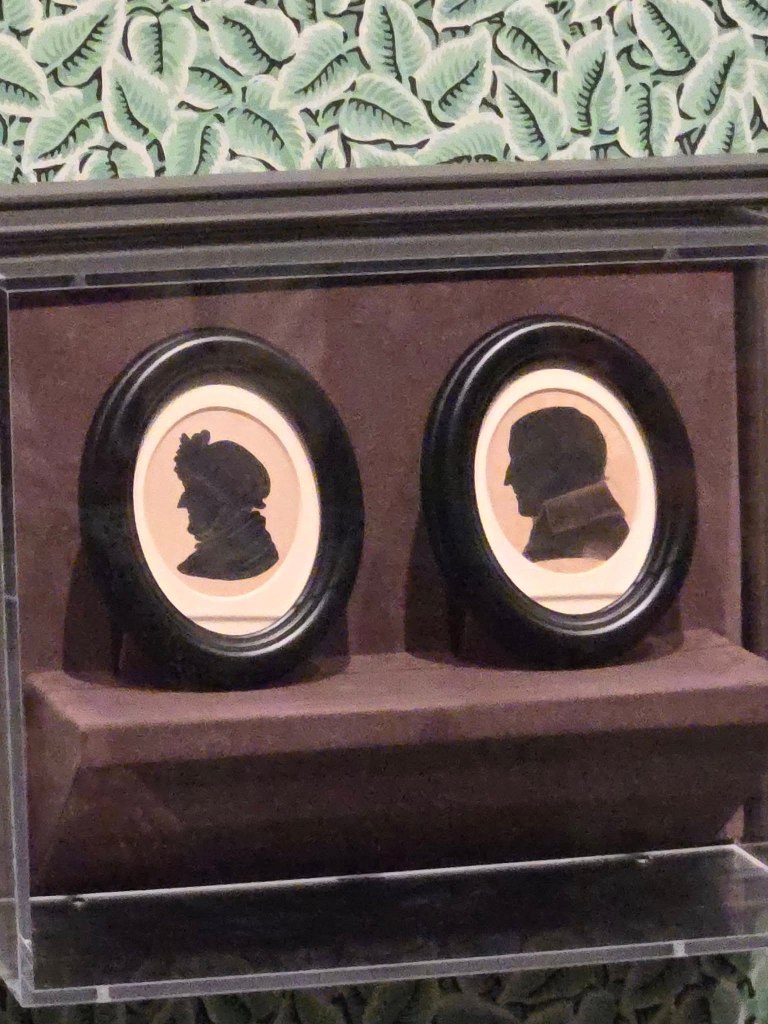

Godmersham Church and Jane Austen’s Family

Jane Austen, in a total of ten months staying at Godmersham, must have attended this church at least forty times. More likely eighty times, if they had morning and evening Sunday services as many churches did at the time. So she would have known it well.

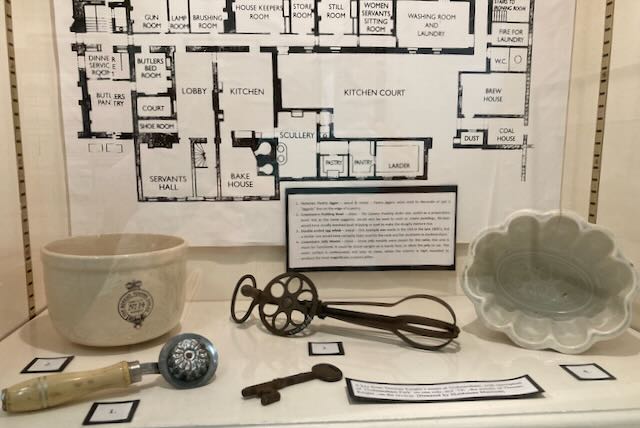

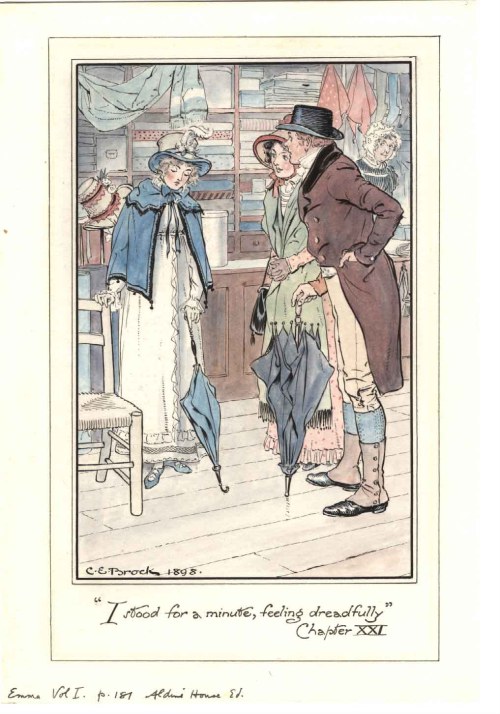

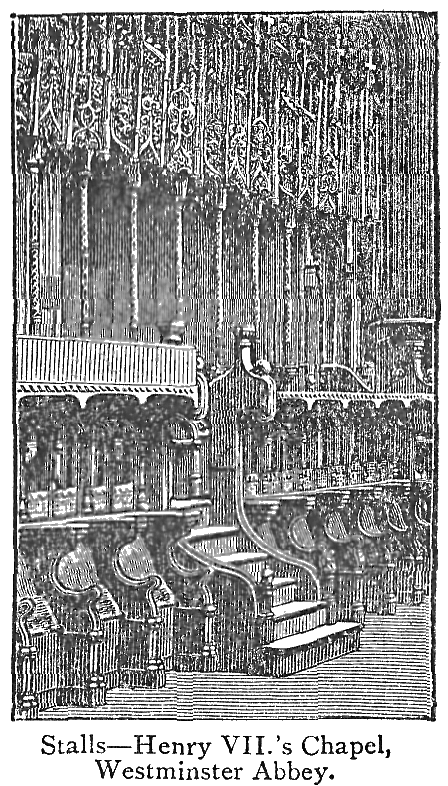

In her time, the chuch had a triple-decker pulpit: a high wooden pulpit with a sounding board over it (a wooden structure reflecting the sound forward), from which the vicar would preach. Below that was the vicar’s “prayer desk,” from which he would lead the service, reading prayers and Scriptures. And below that, the “parish clerk’s pew,” from which the church clerk would lead congregational responses. (These are the three “decks” of the pulpit.) (See another example here.)

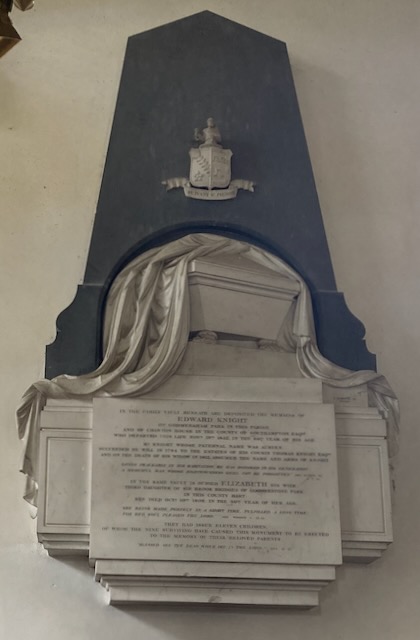

Across the church from this pulpit were two huge “box pews” for the major families of the parish. These were on top of burial vaults, so Austen would have walked up five steps and through an arched doorway to get to the Knight family’s “pew,” actually a separate room which enabled them to see over everyone’s heads to the top pulpit (See pages 70 and 73–pp. 26 and 29 of the pdf file– of The Parish Church of St Laurence). Quite a different experience than her tiny churches at Steventon and Chawton, where only the squire of the area and his family would have a box pew, on a much smaller scale.

Like so many of the Austen-era churches, the Godmersham church was remodeled and expanded in the 1860s. According to the “Souvenir Guide” for the church, at that time “The Georgian furnishings (triple-decker pulpit, parlour pews, western gallery and box pews) were swept away and the entire building restored and refurbished.”

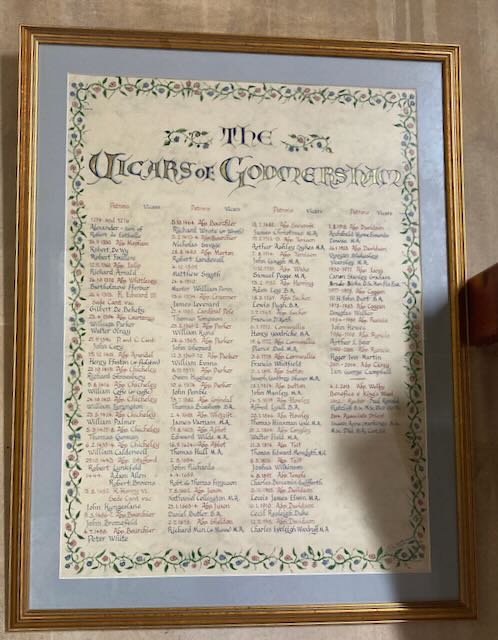

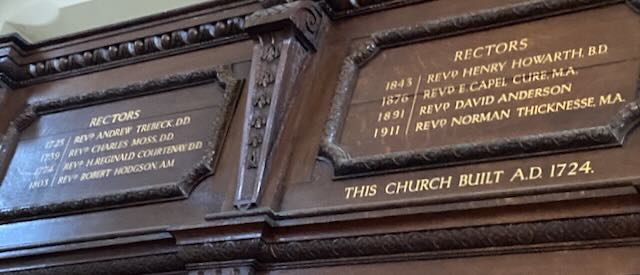

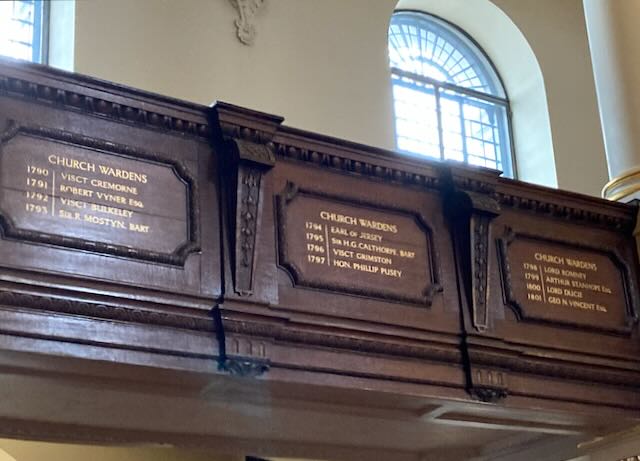

Vicars

The Godmersham church had vicars over the centuries. English churches traditionally either have rectors, who received all the tithes of the parish, or vicars, who received only part of the tithes. For a church with a vicar, a nominal rector elsewhere received the main tithes. The only vicar in Austen’s novels is Mr. Elton, who thus received a lower income and needed to marry money. (Tithes are ten percent of the income of the people of the parish; in Austen’s time, it was legally required that this be paid to the parish priest, in either cash or in agricultural produce. The system and these definitions have changed, of course, in modern times.)

The “rector” of the Godmersham church, who received most of the tithe money, was the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral, meaning the leaders of the Cathedral: the dean, canons, and prebendaries. Much of the parish income went to them, but some went to the vicar, who performed the daily responsibilities of the church and preached and led services. In Austen’s time, Francis Whitfield was vicar (1778-1811), then Joseph Godfrey Sherer (1811-1823). Jane visited Mrs. Sherer, and said in a letter that she liked Mr. Sherer very much (Sept. 23, 1813). She wrote to her brother Frank (Sept. 25, 1813):

“Mr. Sherer is quite a new Mr. Sherer to me; I heard him for the first time last Sunday, and he gave us an excellent Sermon—a little too eager sometimes in his delivery, but that is to me a better extreme than the want of animation, especially when it evidently comes from the heart, as in him. The Clerk is as much like you [Frank] as ever, I am always glad to see him on that account.”

Here we get a personal view of what Jane Austen liked in sermons: not too much emotion, but enough to show that the preacher is speaking from his heart. It reminds me of a section in her unfinished novel The Watsons, where Emma’s father, a clergyman, commends the sermon of the local minister (Emma’s love interest). Sermons were generally “read”:

“He [Mr. Howard] reads extremely well, with great propriety, and in a very impressive manner, and at the same time without any theatrical grimace or violence. I own I do not like much action in the pulpit; I do not like the studied air and artificial inflexions of voice which your very popular and most admired preachers generally have. A simple delivery is much better calculated to inspire devotion, and shows a much better taste. Mr. Howard read like a scholar and a gentleman.”

Austen continues in the same letter,

“But the Sherers are going away. He has a bad Curate at Westwell, whom he can eject only by residing there himself. He goes nominally for three years, and a Mr. Paget is to have the Curacy of Godmersham—a married man, with a very musical wife, which I hope may make her a desirable acquaintance to Fanny.”

A curate was an assistant or substitute clergyman, generally paid a low salary. Mr. Sherer will hold the office of vicar of Godmersham for life, unless he resigns it. But he can hire a curate to take his place while he resides in another parish for which he is presumably also rector or vicar.

Austen mentions several more visits by the Sherers until on Nov. 7 she says they are actually gone, although Mr. Paget has not yet come. As we often see in Austen’s novels, the clergyman was a central person in a country community.

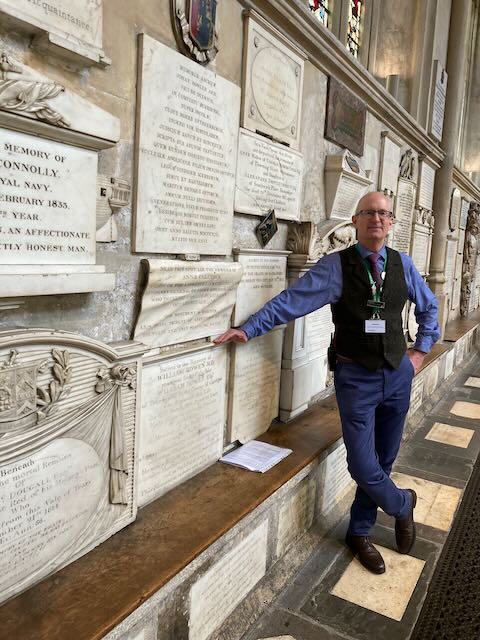

The Godmersham Church Today

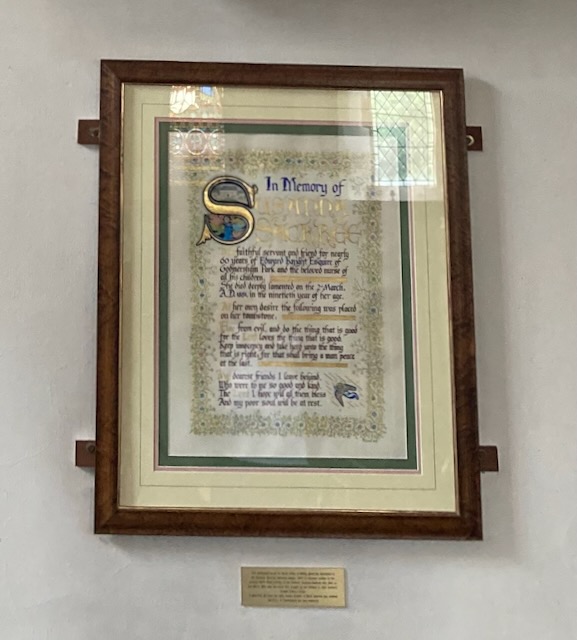

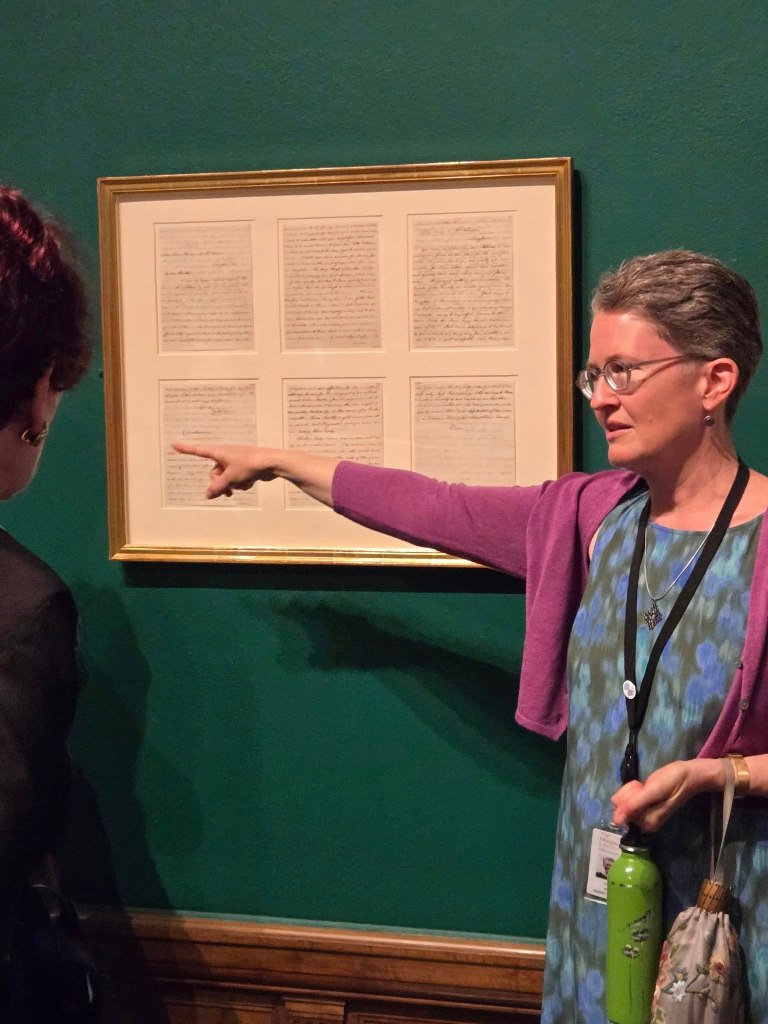

Like so many English churches today, the Godmersham church is now combined with several other churches in the area, and they take turns hosting services. Our guide estimated that there are about three hundred people in the parish, and only 15 or 20 show up for regular Sunday services. However, larger crowds show up for events such as weddings, funerals, baptisms, and church holy days. The church is blessed to have funding from wealthy former owners of Godmersham Park who left money for the church.

Our guide said he loves the peace and quiet of the church area, and enjoys the changes in the seasons, seeing the snowdrops, the daffodils, and the holly berries. The Pilgrim’s Way from Winchester to Canterbury brings modern-day pilgrims down a path next to the church, where they can enjoy it also.

This lovely, historic country church welcomes visitors, but be sure to make arrangements beforehand. And check on visiting hours for the Heritage Centre.

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.

All photos in this post ©Brenda S. Cox, 2026 (except for Deb Barnum’s photo, which is labeled).

For Further Exploration

St. Lawrence the Martyr church at Godmersham

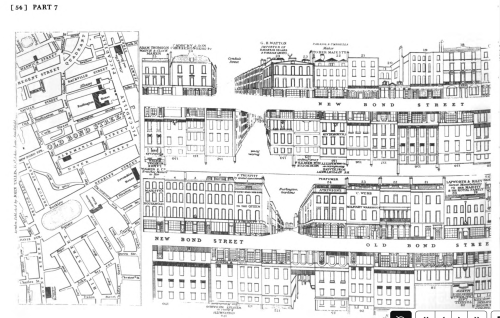

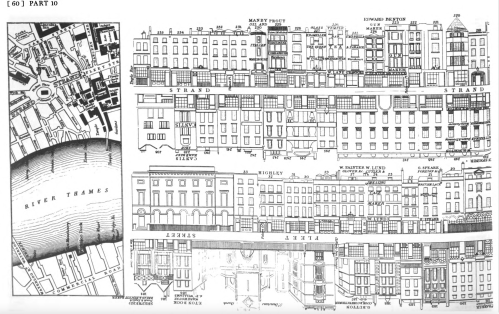

Detailed history of the Godmersham church (pp. 66-77, “The Church in Jane Austen’s Time” includes sketches of the church interior as Austen knew it. Note the huge box pews on p. 73. Austen would have sat in one of these when she was visiting her Knight relatives.)

The reference to Mr. Sherer’s church at Westwell may refer to this church in Kent.

See also Deborah Barnum’s post.

Other Austen Family Churches

Hamstall Ridware and Austen’s First Cousin, Edward Cooper

Adlestrop and the Leigh Family

Stoneleigh Abbey Chapel and Mansfield Park

Great Bookham and Austen’s Godfather, Rev. Samuel Cooke

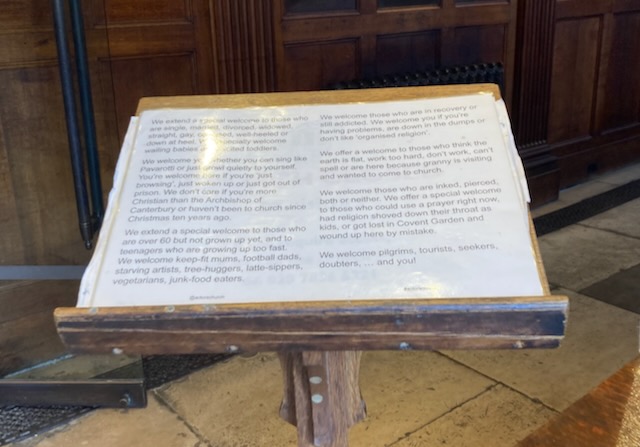

St. Paul’s Covent Garden (with links to other churches mentioned in Austen’s writings)