Mutton

Gently stir and blow the fire,

Lay the mutton down to roast,

Dress it quickly, I desire,

In the dripping put a toast,

That I hunger may remove —

Mutton is the meat I love.

On the dresser see it lie;

Oh, the charming white and red;

Finer meat ne’er met the eye,

On the sweetest grass it fed:

Let the jack go swiftly round,

Let me have it nice and brown’d.

On the table spread the cloth,

Let the knives be sharp and clean,

Pickles get and salad both,

Let them each be fresh and green.

With small beer, good ale and wine,

Oh ye gods! how I shall dine.” — Jonathan Swift (1667 – 1745)

Inquiring readers: After reading Jonathan Swift’s poem, Mutton, I was reminded of the importance of pleasurable dining and the immense satisfaction a good meal gives us. While I understand much of the poem, which still feels fresh, some phrases and customs prompted me to look up the differences between dining customs in the mid-18th century and today.

While Jonathan Swift died 30 years before Jane Austen’s birth, his reputation as a writer, thinker and essayist must have been well known to her and her father, who most likely kept the author’s writings in his extensive library.

Annotations:

“Gently stir and blow the fire”:

Stirring the hot coals while blowing the fire with bellows increases the temperature to the desired heat for cooking the meat.

Image josephjenkinsantiques.co.uk

18th century elm and leather fireplace bellows

“Lay the mutton down to roast,

Dress it quickly, I desire,

In the dripping put a toast,

That I hunger may remove”

As the meat sizzles and browns, the drippings, or the fat rendered from roasting, are captured by a dish placed under the meat. The fat from beef is used to make yorkshire pudding: in this situation, mutton drippings are eaten with toast.

“Mutton is the meat I love.

On the dresser see it lie;”

“Although they looked much more like what we would call a sideboard, the earliest use of the word dresser dates to 16th-century England. Used in the kitchen and dining areas, these early incarnations provided extra space for serving and “dressing” meats headed to the dining table and were essentially side tables with a single row of drawers that rested atop tall legs.” – Dressers, Rau Antiques

“Oh, the charming white and red;

Finer meat ne’er met the eye,”

Swift’s description of red and white meat is shown in this 1762 Schaak image of a tavern interior.

Tavern Interior, John Schaak, 1762, Wikimedia

“On the sweetest grass it fed”

Swift describes sheep that were fed in pastures with fresh green grass. We are all familiar with the bucolic engravings and paintings of that era of shepherds and sheep dogs or border collies looking after the flocks and bringing them to new pastures. — Glossary of sheep husbandry – Wikipedia

“Let the jack go swiftly round,

Let me have it nice and brown’d.”

“Roasting jacks (or spit jacks) were used in the kitchen to facilitate grilling meat or other dishes on a spit in an open fire by rotating (or turning) the spit.” – Spit Jacks: See image in this link.

We have no way of knowing whether Jonathan Swift enjoyed his mutton at home or in a tavern, as in the Schaak image. The latter would have been quite common for a bachelor. Swift, however, was a successful man who could afford servants to cook and serve this meal at home or arrange for more private accommodations in an inn.

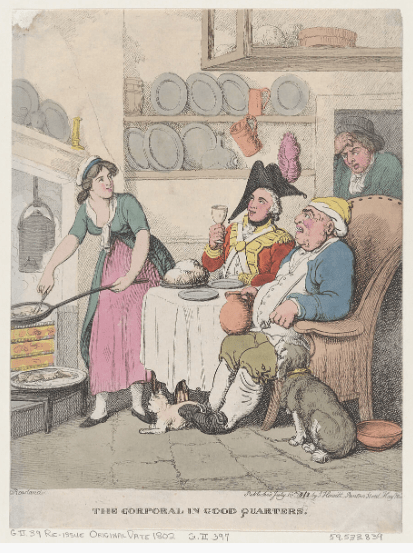

The Corporal in Good Quarters, Thomas Rowlandson, Met Museum, Public Domain

“On the table spread the cloth,”

Swift might have dined in a more intimate setting instead of a busy tavern room. This 1802 cartoon by Thomas Rowlanson demonstrates the white table cloth and cozy setting. The Corporal in Good Quarters, Met Museum, Public Domain, 1802

“Let the knives be sharp and clean,”

Image: European Eating Utensils, 16th-18th Century – Tailor & Arms

Image: European Eating Utensils, 16th-18th Century – Tailor & Arms

Eating utensils, interestingly enough, didn’t change much for the poorer citizens from the medieval period to the industrialisation. This replica set of eating utensils is modeled from originals found in the UK and was used during the 18th century.

Vegetables:

“Pickles get and salad both,

Let them each be fresh and green.”

Pickles:

“Pickles aren’t limited to the dill and cucumber variety. They can be sweet, sour, salty, hot or all of the above. Pickles can be made with cauliflower, radishes, onions, green beans, asparagus and a seemingly endless variety of other vegetables and fruits. When the English arrived in the New World, they brought their method for creating sweet pickles with vinegar, sugar and spiced syrup.” – History in a Jar: The Story of Pickles

Salad:

Salad during Swift’s time was known as salmagundi, a 17th-18th century form of a composed and layered salad that we know today as a chef’s salad. Components varied throughout the year according to the foods available. These salads were either made with fresh greens or with vegetables that were boiled. The links below lead to recipes used during this period.

Libations:

“With small beer, good ale and wine,”

Small Beer:

Throughout the middle ages, drinking water was unpleasant and unsafe to consume and milk was far too expensive for most people. Instead, a mildly alcoholic drink known as ‘small beer’ was brewed and consumed for its hydrating and nutritional properties in households, workplaces and even schools across Britain. Typically brewed to around 2.8% ABV (alcohol by volume), small beer became a staple of British daily life and was even cited in Shakespeare’s works. – What is Small Beer & When Was it Brewed?.

Difference Between Beer and Ale:

According to Wikipedia, “Ale is a type of beer brewed using a warm fermentation method, resulting in a sweet, full-bodied and fruity taste. Historically, the term referred to a drink brewed without hops.” Beer or lager combined hops with other ingredients.

“As hops began to pervade breweries … this distinction between beer and ale no longer applied. Brewers began to differentiate between beer and ale on the basis of where the yeast fermented in the cask: ale uses yeast that gathers on the top, and lager uses yeast that ferments on the bottom.” – What is the Difference Between Beer and Ale?

The Ale House Door, Henry Singleton, 1790, Wikimedia

The Ale House Door, Henry Singleton – Serving ale in a country setting, ca. 1790

At the start of the 18th century, increased taxes on malt and hops to finance war with France, induced brewers to move to brewing more beer. Their reasoning was simple: the tax on malt was more than that on hops. Ale used more of the former, beer more of the latter.” – Early 18th century British beer styles

The above article explains the difference between small beer and ale in both strength and color. Beer was made for immediate consumption, and ales were drunk as soon as they had “cleared” in three or four weeks.

Wine

Poor people tended to drink beer or gin, but a wider range of alcoholic drinks was available to the rich. These included wines such as French claret; fortified wines such as sherry, port or Madeira; and spirits such as brandy and rum. – Jane Austen’s World, Elder Wine, A Perfect Libation for a Regency Holiday

Madeira image from the George Washington Presidential Library @ Madeira · George Washington’s Mount Vernon

Final line of the poem:

“Oh ye gods! how I shall dine.”

Conclusion:

In April, 1768, Pastor Woodforde described a get together at Lower House with Mrs Farr, presumably the hostess. His description of the dances and food served gives us an intimate view of ordinary get togethers only decades after Swift’s death. Notice the mention of a roasted shoulder of mutton, the paltry serving of vegetables, and alcoholic drinks:

April 19. … We had some Country Dancing and Minuets at Lower House…We were very merry and no breaking up till 2 in morning. I gave Mrs. Farr a roasted Shoulder of Mutton and a plum Pudding for dinner — Veal Cutlets, Frill’d Potatoes, cold Tongue, Ham and cold roast Beef, and eggs in their shells. Punch, Wine, Beer and Cyder for drinking.” – The Diary of a Country Parson, the Reverend James Woodforde, full text Internet Archive

Food Poetry:

- A Receipt for a Pudding by Mrs. Austen

- I taste a liquor never brewed – Summary & Analysis by Emily Dickinson

More links to this topic:

Inside of a Country AlehouseDate: published March 1, 1797, William Ward (English, 1766-1826) after George Morland (English, 1763-1804) Art Institute of Chicago

- Beverages in the Georgian Era – Part 2 | The Historic Interpreter

- The Great British Pub, Historic UK

- A Most Wholesome Liquor: A Study of Beer and Brewing in 18th-Century England and Her Colonies | Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library

- Issue 30: Cooking for the Georgians — Jane Austen Literacy Foundation

- 18th Century Cookery Books and the British Housewife | Jane Austen’s World

- Turnspit dogs: Jane Austen’s World

Loved Swift’s poem – it made me feel hungry, as surely all written descriptions of food should! And Parson Woodforde’s diary has been part of my reading for so long; he tells us so much of everyday 18th century life and wonderful observations on his relatives – and often their shortcomings. He also describes for us what food was served at his Norfolk parsonage, and what everyday purchases of food and other items were made, adding so much to our knowledge of the social history of his times.

Awesome annotations, thanks Vic! The turnspit dogs were referenced in a Sayers novel I read recently, so I appreciate the explanation. Poor little fellows!

Dear Vic, I enjoyed this post so very much! Everything about it – the poem, the explanations, the links, especially the one on salads, which sounded so good I am tempted to try them…though things like sorrel and borage may not be easy to find. Anyway, thanks for this pleasure.

Reblogged this on Romance Writers of Atlantic Canada.

I have saved this post both for the interesting social information and for the recipes. I adore bread pudding and I found the use of the yolks of hard cooked eggs much more reasonable than raw yolks, Our fore-mothers knew good food! And they could cook it without microwaves, instant pots, air fryers and all the other paraphernalia we depend on today!

Fantastic post and wonderful deconstruction for explanation.

denise

Wonderful information, Vic. For those who live in NYC, Keen’s at 36th St has a mutton chop on offer, or it might be a slightly younger lamb offering.