For years, I’ve loved the Penguin Random House “Puffin in Bloom” editions of Anne of Green Gables, Heidi, Little Women, and A Little Princess. I typically purchase these gorgeous books as gifts for my bookish friends and their daughters.

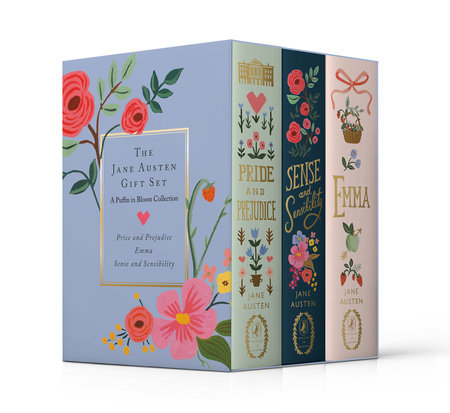

Now, the Puffin in Bloom line has expanded to include three of Jane Austen’s novels as well!

Delectable Classic Covers

The Puffin in Bloom line started with four classic, coming-of-age novels: Anne of Green Gables, Heidi, Little Women, and A Little Princess. These hardcover classics feature floral cover illustrations by Anna Bond, the creative director and artistic inspiration behind the global stationery phenomenon Rifle Paper Co. Puffin in Bloom became an instant success and the original foursome continues to fly off the shelves. Classics novels with such beautiful covers do not disappoint!

Each book can be purchased individually or as a boxed set in a beautiful keepsake box. These hardcover books don’t just boast a pretty cover; they look and feel great in your hands. They are just the right size and they read well. I am very particular about the feel of a book in my hands, and these are a joy to hold and read. You can easily slip them into a purse or tote to take with you, too!

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

To commemorate the 150th anniversary of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderful by Lewis Carroll, Puffin Books added to the Puffin in Bloom line and released a deluxe, hardcover gift edition of the famous novel. Once again, the talented Anna Bond created the cover illustration, and she also provided full-color illustrations inside. The result is exquisite!

“In this beautiful edition, Alice’s story comes to life for a whole new generation of readers through the colorful, whimsical artwork of Anna Bond, best known as the creative director and artistic inspiration behind the worldwide stationery and gift brand Rifle Paper Co.”

Jane Austen in Bloom

After years of waiting and wondering (and wishing), I was overjoyed when Penguin announced last year that they were planning to expand the Puffin in Bloom line to include other classics as well. Again, they chose Anna Bond to create new cover art with her signature style. But best of all, they chose our Jane’s cherished novels for this new endeavor!!

This first installment (I truly hope there will be more) includes Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, and Emma. Let’s take a closer look:

Pride and Prejudice

Though her sisters are keen on finding men to marry, Elizabeth Bennet would rather wait for someone she loves – certainly not someone like Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy, whom she finds to be smug and judgmental, in contrast to the charming George Wickham. But soon Elizabeth learns that her first impressions may not have been correct, and the quiet, genteel Mr. Darcy might be her true love after all. You can view and purchase HERE.

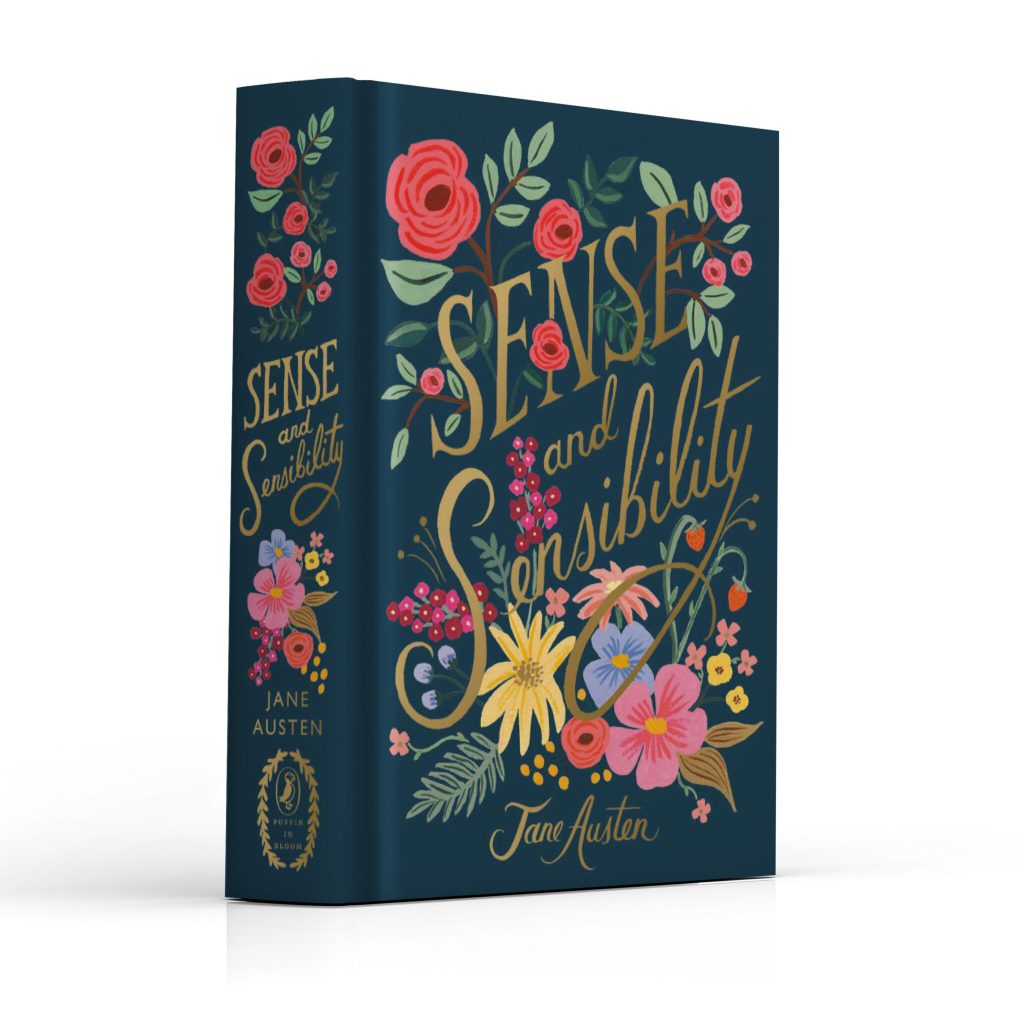

Sense and Sensibility

Book Description: “Marianne Dashwood wears her heart on her sleeve, and when she falls in love with the dashing but unsuitable John Willoughby, she ignores her sister Elinor‘s warning that her impulsive behavior leaves her open to gossip and innuendo. Meanwhile Elinor, always sensitive to social convention, is struggling to conceal her own romantic disappointment, even from those closest to her. Through their parallel experience of love– and its threatened loss–the sisters learn that sense must mix with sensibility if they are to find personal happiness in a society where status and money govern the rules of love.” You can view and purchase HERE.

Emma

Book Description: “Emma Woodhouse believes herself to be an excellent matchmaker, though she herself does not plan on marrying. But as she meddles in the relationships of others, she causes confusion and misunderstandings throughout the village, and she just may be overlooking a true love of her own.” You can view and purchase HERE.

Anna Bond

Anna Bond is co-founder and CCO of Rifle Paper Co., an international stationery and lifestyle brand with offices in Winter Park, Florida and New York City. Originally from Summit, New Jersey, Anna trained as a graphic designer and made her way to Florida to work as a senior art director at a media company at age 21. After a year of working in print design she left to pursue her passion in illustration. A number of gig posters and freelance work later, she re-discovered her lifelong love of stationery through wedding invitation design and the idea for a stationery collection was born.

Together with her husband Nathan, Anna launched Rifle Paper Co. based out of their apartment in November 2009 and the brand has quickly grown to become of the most notable brands in the industry. Every one of Rifle’s over 900 products are designed by Anna and feature her signature hand-painted illustrations, vibrant color palette, and whimsical tone which has helped propel the brand’s success. Rifle Paper Co. now employs over 200 people and is carried in over 5,000 stores around the world including Anthropologie, MoMA and Barnes & Noble. You can see more of Anna’s work HERE.

Collecting Austen Covers

With covers like these, who can resist “just one more” edition of Austen’s beloved novels? I know many of us have shelves with several pretty editions, plus a favorite, worn-in version that we keep close by for regular reading. Do you have several editions of Austen’s novels? Which books do you collect and how many do you have so far?

RACHEL DODGE teaches college English classes, gives talks at libraries, teas, and book clubs, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling author of The Little Women Devotional, The Anne of Green Gables Devotional and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. Now Available: The Secret Garden Devotional! You can visit Rachel online at www.RachelDodge.com.