Inquiring readers,

Today is Valentine’s day, a perfect time to revisit some of Jane Austen’s most romantic and memorable quotes.

I can listen no longer in silence. I must speak to you by such means as are within my reach. You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope. Tell me not that I am too late, that such precious feelings are gone forever. I offer myself to you again with a heart even more your own…I have loved none but you.” – Captain Wentworth, Persuasion

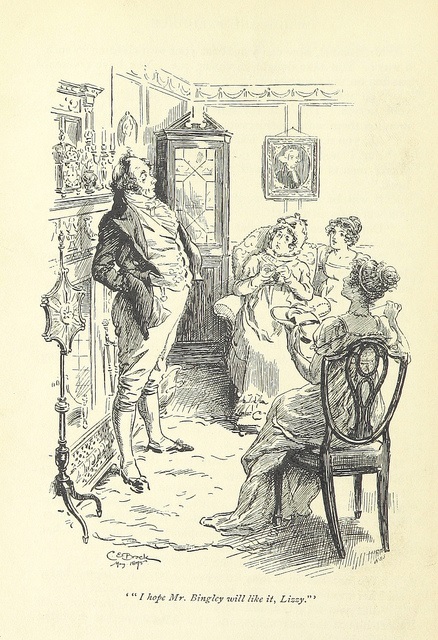

The driving force behind this quote was a talented and witty, yet ordinary-looking spinster. The sentiments expressed in her novels were remarkable given that Austen lived in an era when money and status were considered primary reasons for courtship and marriage.

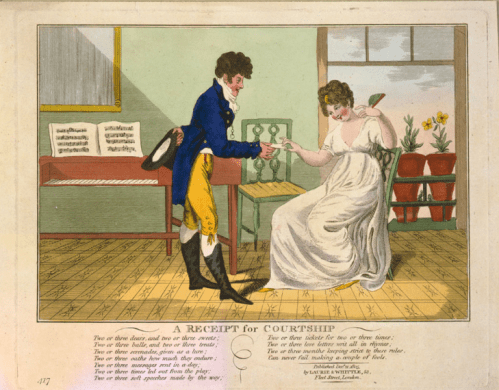

This caricature, created in 1805, poked fun at the era’s courtship conventions, much like Jane Austen did through characters like Mr. Elliot, Mr. Collins, and Henry Crawford, all of whom followed current courtship conventions but misread their heroines exceedingly.

Image in the public domain, U.S. Library of Congress

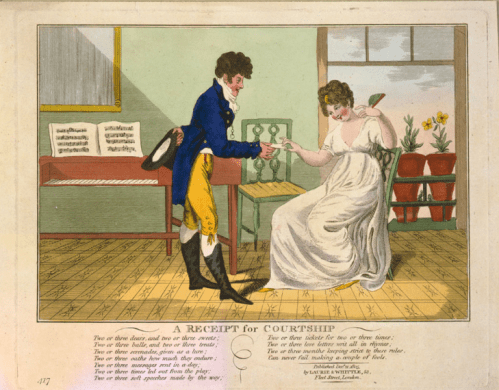

Receipt for Courtship – Text

Two or three dears, and two or three sweets;

Two or three balls, and two or three treats;

Two or three serenades, given as a lure;

Two or three oaths how much they endure;

Two or three messages sent in a day;

Two or three times led out from the play;

Two or three soft speeches made by the way;

Two or three tickets for two or three times;

Two or three love letters writ all in rhymes;

Two or three months keeping strict to those rules,

Can never fail making a couple of fools.

A lady’s imagination is very rapid; it jumps from admiration to love, from love to matrimony in a moment.” – Mr. Darcy’s sarcastic comment to Miss Bingley, Pride and Prejudice

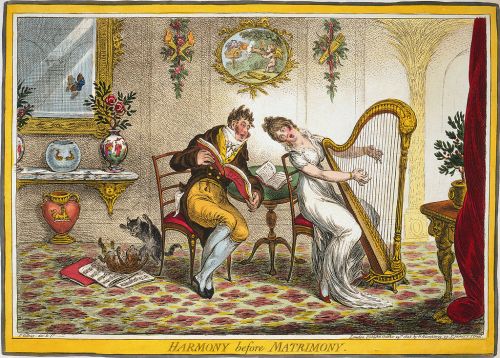

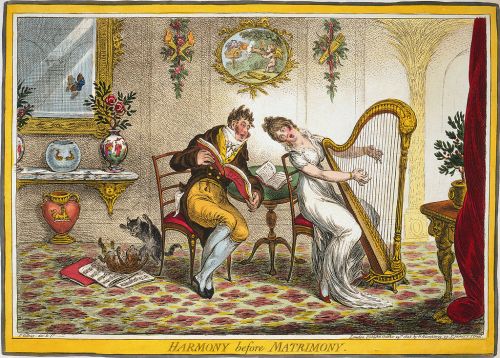

Image in the public domain, Wikimedia Commons

This 1805 caricature entitled “Harmony before Matrimony” of a courting couple would have the young lady assume that a proposal would soon be in the offing. The artist made sure that the viewer understood this through iconography: the cupid in the oval painting, which also shows two courting doves, the two roses in a vase featuring a Chinese couple, the two fish, the two playful cats, a wall sconce made of cupid’s arrows, the two flaming torches, and the butterfly reflected in the mirror making two. The couple sit on a carpet of roses, the music book, “Duets de L’Amour,” is held by the courting swain, while on the table lies an open copy of Ovid’s “Art of Love.” In this scene, all is harmonious, all is good, but those familiar with the caricatures of the engraver James Gillray know that not “all” is what it seems.

The second companion cartoon “Matrimonial Harmonics” depicts life after marriage: Cupid is dead in the funereal image, two parrots sit in their cage with their backs to each other, a dog barks at a hissing cat, the husband covers his ear as his baby screeches in the maid’s arms, and his wife sings alone at the piano forte. It is a scene of inharmonious conflict, one often described by Jane Austen (Mr. and Mrs. Bennet, John and Frances Dashwood, Charlotte and Mr. Collins, Mr. Wickham and wife Lydia).

If I loved you less, I might be able to talk about it more.” ― George Knightley, Emma

Jane’s Heroes were men of few words as this quote by Mr. Knightley attests. A number of Jane Austen’s heroes were men of few words, but Elinor Dashwood and Fanny Pricem two long-suffering heroines, also had difficulty expressing their emotions.

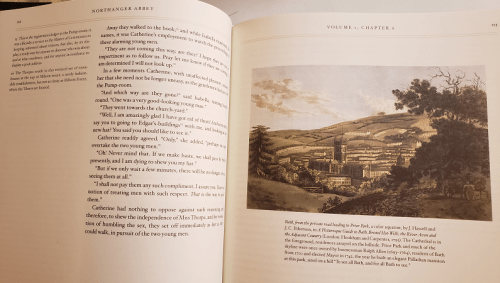

Image in the public domain, wikimedia commons.

This 1786 painting of The Rev. and Mrs. Thomas Gisborne, of Yoxhall Lodge, Leicestershire by Joseph Wright of Derby depicts a sober couple much in the vein of Elinor Dashwood and Edward Ferrars or Fanny Price and Edmund Bertrum. The year the portait was painted precedes Jane’s era, but the calmness of the scene and the sober mien of a couple who clearly come from the gentry class remind me very much of how I envisioned both couples. Neither seem to be the type to behave in in unseemly manner at an assembly ball.

In Jane’s novels, lovers who behaved badly often expressed good insights tinged with regret.

“Where the heart is really attached, I know very well how little one can be pleased with the attention of any body else. — Isabella, Northanger Abbey

and

Yes, I found myself, by insensible degrees, sincerely fond of her; and the happiest hours of my life were what I spent with her.— Mr. Willoughby, Sense and Sensibility

Thumbnail of Johan and Engelke Christian, 1797, by Jens Juel

Older sensible couples who weathered married life and its vicissitudes and remained happy together play prominent roles in Austen’s plots. One senses that Admiral and Mrs Croft who befriend Anne Ellito in Persuasion must have observed the kind attention that Caption Wentworth paid her when he thought no one was looking.

The sensible older couple in Pride and Prejudice are Mr & Mrs Gardiner. He is silly Mrs. Bennet’s brother and a relation over whom Elizabeth did not need to blush. Their calmness and common sense helped to unite Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth after many missed opportunities.

Romantic gestures change for many older couples. Over the years they are comfortable with each other. With age, often physical comfort and health have priority over more youthful pursuits. In her novels Jane Austen ignored the prurient, yet she lived in the Georgian age where social and political cartoons or satire were often graphic. Families took care of each other in sickness and health. They bathed their sick and tended to their every need. One wonders what was in Jane’s private letters to Cassandra regarding the more ordinary tasks of life.

The above image shows the sweetness of an older couple enjoying in tandem the latest fad in Baton-powered enemas. They seem happy and content and at ease with each other!

Jane, however, never found such a mate for life.

To you I shall say, as I have often said before, Do not be in a hurry, the right man will come at last.” – Jane Austen’s Letter to Fanny Knight

Following Jane’s advice, Fanny married for keeps. She bore 9 children to Sire Edward Knatchbull a baronet, to whom she was married for 26 years until his death.

Jane’s heroines were astute about pledging their love. Elizabeth Bennet failed to see through Wickham’s falsehoods at first, but common sense prevailed. Anne Elliot was never quite enamored of slimy William Elliot, for her heart belonged to the infinitely superior Caption Wentworth. One of Anne’s more memorable quotes is:

“My idea of good company, Mr. Elliot, is the company of clever, well-informed people, who have a great deal of conversation; that is what I call good company.” – Persuasion

One can only surmise that rather than settle for marriage to just any man, Jane Austen chose good company over a less than perfect union.

Jane’s heroes were equally steadfast and saw through foibles, insecurities, and prejudices of the women they loved, especially when their first impression was. They, like Mr. Darcy, waited patiently for the right moment to reveal their true feelings:

“My real purpose was to see you, and to judge, if I could, whether I might ever hope to make you love me.”— Darcy, Pride and Prejudice

In my opinion, none of Jane’s true heroes and heroines were ridiculous or maudlin. They chose well and understood the meaning of true love.

More on the topic:

Read Full Post »

Inquiring readers, It is confirmed!! Sanditon, Jane Austen’s last unfinished fragment of a novel has been adapted for television as an 8-episode mini-series by Andrew Davies, who adapted 1995’s Pride and Prejudice for the small screen. Mr. Davies uses his talents and knowledge of Jane Austen and British history to finish the novel that Jane laid aside months before her death. The mini-series includes nude bathing (an historically accurate touch) and, to paraphrase Mr. Davies, is somewhat “sexed up.” (Town and Country Magazine.)

Inquiring readers, It is confirmed!! Sanditon, Jane Austen’s last unfinished fragment of a novel has been adapted for television as an 8-episode mini-series by Andrew Davies, who adapted 1995’s Pride and Prejudice for the small screen. Mr. Davies uses his talents and knowledge of Jane Austen and British history to finish the novel that Jane laid aside months before her death. The mini-series includes nude bathing (an historically accurate touch) and, to paraphrase Mr. Davies, is somewhat “sexed up.” (Town and Country Magazine.)