Question: How do you think Charlotte Brontë would have felt being showcased on a blog for and about Jane Austen? It is well known that Charlotte had no love for Jane’s novels or writing style.

Syrie James: I think that Charlotte would be astonished to find herself showcased anywhere at all today! Trying to imagine her response to the worldwide adoration of her novel “Jane Eyre,” not to mention the computer and the internet, simply boggles the mind. Although Charlotte found Jane Austen’s novels lacking in passion and deeply felt emotion, she did admire Austen’s ability to construct a story, saying that Austen employed “an exquisite sense of means to an end.”

Question: What did you use as your sources for Charlotte Bronte’s life? Did you think that Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography was still relevant? I absolutely loved The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen — definitely one of my favorite Austen-inspired works. I felt you’d absolutely captured Austen’s “voice.” In writing a novel based on Bronte next, did you find it difficult to transition to a new narrator? Did Austen ever “slip” back into your writing?

Syrie James: It was thrilling to write in Charlotte’s voice! To prepare, I read all of Charlotte’s novels over and over, and more than 400 of her preserved letters. Then I just let the novel flow. The difficult part was to avoid Americanisms and anachronisms, which meant checking words throughout the text to be sure they existed and were employed in England in 1854. I found it easier to write in Charlotte’s voice than Jane Austen’s, because Charlotte was far more passionate! I have a shelf full of dozens of Brontë biographies which I used as sources (in addition to Charlotte’s voluminous preserved correspondence), but one of the best is “The Brontës” by Juliet Barker.

Although we know that Mrs. Gaskell was prejudiced in Charlotte’s favor (having been her dear friend), her biography is absolutely relevant and in fact remarkable, since she actually knew Charlotte, visited all the locations in the story herself, and personally interviewed many of the key people in Charlotte’s life.

Question: Besides the literary research, what other methods did you employ in helping to bring about the authenticity of the book? I really loved The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen.

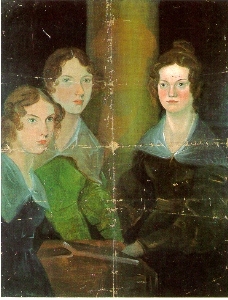

Syrie James: I am so glad you loved The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen and hope you enjoy The Secret Diaries of Charlotte Brontë just as much, for it was truly a work of my heart. In addition to reading dozens of Brontë biographies, everything I could find about Mr. Nicholls, all of Charlotte’s correspondence, most of the Brontë poetry (they wrote hundreds of poems), and all of the sisters’ novels, I also studied the art of the Brontës (Charlotte, Emily, and Anne were all accomplished artists). I spent two days visiting the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, England– which is the house where Charlotte and her family lived almost her entire life, and is filled with their possessions. I haunted the rooms where Charlotte lived and worked, walked the lanes that she walked, visited the church where her family is buried, and really soaked up the atmosphere of the place. I was also granted a private tour of Roe Head School (from attic to cellar!), a very influential school which Charlotte attended, and which you will read about in my novel. It was invaluable to have those images in my mind when I wrote the book. After that, I just imagined myself in Charlotte’s shoes, and did my best to channel her remarkable spirit while telling her story!

Question: My question is what was your original inspiration to go for the diary style of writing?

Syrie James: I decided to “go for the diary style of writing” with my first novel, The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen, because I the story I wanted to tell was so personal. I felt that readers would connect more to Jane if they could read the untold story of her love affair, and how it influenced her return to writing, in the first person point of view–as if from her own pen. The first book was so well-received, it seemed only natural to write my next novel in the same manner, this time relating the true story of the author of another one of my all-time favorite novels, “Jane Eyre”!

How did Charlotte Brontë come to write that novel, and all her other books? How much of her work was based on her life? Did she ever fall in love and marry? How is it that three sisters living in the wilds of Yorkshire came to become published authors at the exact same time, writing novels that are still so beloved and popular today? I wanted to write that story as if Charlotte was telling it herself.

Question: What inspires you to choose a topic/subject to write about? In your research, did you discover anything surprising about the Brontës?

Syrie James: For my first two books, I chose challenging topics which meant a great deal to me. I decided to “become” my favorite authors, so that I could not only tell their love stories, but also showcase their love of writing and their personal struggles on the road to becoming published authors–a subject I could truly relate to.

Syrie James: For my first two books, I chose challenging topics which meant a great deal to me. I decided to “become” my favorite authors, so that I could not only tell their love stories, but also showcase their love of writing and their personal struggles on the road to becoming published authors–a subject I could truly relate to.

You asked, “did you discover anything surprising about the Brontës?” Everything I learned surprised me, because when I started my research I knew nothing about them! I was astonished to discover the incredible volume of writing the Brontës did as children, and what wonderful artists and poets the sisters were. I was surprised to learn that Charlotte was secretly in love with a married man, and that he was the partial inspiration for many of the heroes in her novels. I was touched to learn that Mr. Nicholls was secretly in love with Charlotte for so many years, before he had the nerve to propose. It’s a remarkable story, and the Brontës were a complicated and fascinating family.

Question: My question is completely tongue in cheek…I recently visited Haworth and was blown away by those little tiny books that contained Charlotte and her siblings juvenelia. When you wrote the Secret Diaries, did you feel compelled to write it with pen and ink in a microscopic hand? Looking forward to reading this book–sounds absolutely terrific.

Syrie James: It’s funny that you should mention those tiny little books that Charlotte and her siblings wrote as children. My husband and I actually got to hold one of those microscopic books and read it (it was about 1 inch x 2 inches), when we were granted a private viewing at the Brontë Parsonage library. How they ever wrote in such a tiny hand is beyond me.

Question: I have not read a Jane Austen book but have watch the movies. I love them. I am just beginning to read books from the Regency-era. Do you have any other authors you recommend? Which book should I begin with that has been written by Jane Austen? Why?

Syrie James: I always recommend that newcomers to Jane Austen begin with Pride and Prejudice. It’s a classic story, extremely well-written, perfectly plotted, has unforgettable characters, and it pulls you in from the very first chapter.

Thank you for taking the time to answer these questions, Syrie. Look for my review of The Secret Diaries of Charlotte Brontë this weekend.

In December 1859, Florence Nightingale wrote this letter of recommendation to Parthenope Verney:

In December 1859, Florence Nightingale wrote this letter of recommendation to Parthenope Verney: