Inquiring readers, Tony Grant, a blogger and contributor to this blog for a decade, has submitted this interesting post about Netley Abbey. He ties history, literature, poetry, and painting to Jane Austen’s fascination with the gothic novel, which led to her writing Northanger Abbey in her wonderfully satiric vein. Enjoy!

My Memories of Netley Abbey

When I was eight years old, I recall one of my grandmothers telling me about the ghosts that haunted Netley Abbey. Netley Abbey is four miles along Southampton Water from where I grew up. I lived in Woolston, a small industrial area of Southampton next to the Itchen River, which flows into Southampton Water at the cities docks. (See Google satellite map image below and Google map image alongside it.)

Google sattelite image

Google map image

Within walking distance of where I lived are extensive areas of woodland and farms that specialized in market gardening. Netley Abbey itself is set within woodland near the shore of Southampton Water, not far from The Hamble River and within view of the Isle of Wight.

Google street view: Entrance to Netley Castle

I remember my grandmother telling me about a White Lady, who has been seen on occasions wafting through the ruins of Netley. She reputedly had been incarcerated within a bricked up space within the Abbey. Quite a horrific thought. She told me also of the dark presence of a black clad monk that sometimes appeared in the ruined entrances to the cloisters within the Abbey’s precinct.

Netley Abbey’s ruined walls and pillars: Image Tony Grant

Another story tells of a builder at the beginning of the 18th century, when the Abbey’s stones and bricks were being recycled as building material, and how part of the arched window at the western end of the abbey church fell on him, fatally injuring him. Stories like this, imagined and real, were useful in keeping Netley Abbey in a substantial state. These stories became vivid images in the mind of a small boy.

Netley Abbey arches. Image Tony Grant

My friends and I would walk to Netley or take the green Hants and Dorset bus there. We clambered over the ruins of the Abbey in daylight, imagining what might happen at night, especially in the dim glow of a full moon and with the hooting of owls. Many trees around the Abbey have crows nests high up in their branches and the harsh echo of their shrieking almost always pervades the air around and above the Abbey ruins. I remember our young selves feeling scared and worried but drawn helplessly to this haunted place.

Early History of the Abbey

Netley Abbey is the most complete set of Cistercian monastic ruins in England. Peter de Roches, the Bishop of Winchester founded Netley in 1238. Unfortunately, he died soon after and before building work on the Abbey had begun. However, a group of monks from Beaulieu Abbey in The New Forest arrived in Netley a year later, in 1239, and probably lived in wooden huts while the Abbey was under construction. King Henry III (1216-1272) became the patron of Netley. On one of the remaining stone pillar bases inside the church ruins, a clear inscription shows Henry III’s name.

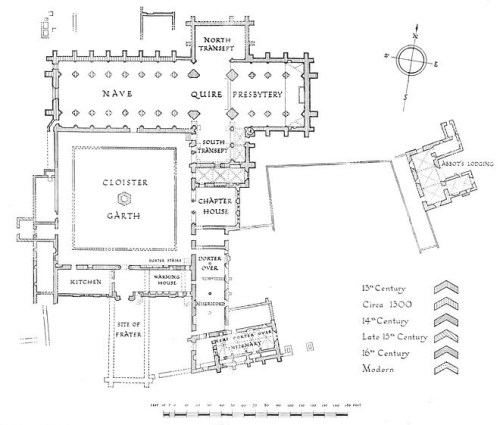

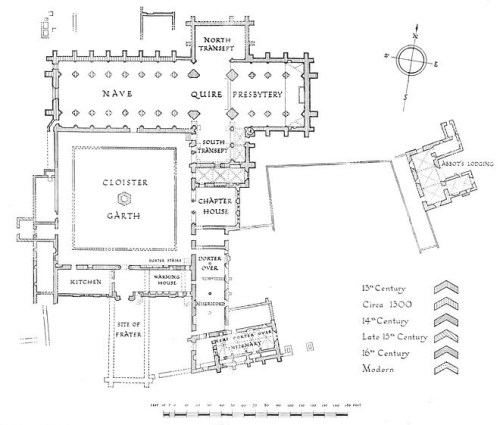

Map of Netley Abbey ca. 1300 – modern times

The Cistercians were an order founded by Robert Molesme in 1089. He was a Benedictine who felt that the Benedictines had abandoned the life of simplicity the rule of St Benedict stated. He set about rectifying this. The monks set up an Abbey at Citeaux in France that gave them their name, Cistercian. They returned to a life of manual work and prayer and dedicated themselves to the ideal of charity and self-sustenance. This is very much the lifestyle the monks at Netley followed.

Fifteen monks and thirty lay brothers lived at Netley, along with officials and servants. They provided sustenance and shelter to travelers and extensively farmed the land around Netley. Interestingly, only a few miles away St. Mary the Virgin, Hound Parish Church, at nearby Hamble le Rice on the Hamble River, was founded by Benedictines separately from the Cistercians at Netley. Bishop Giffard of Winchester had established a cell of Benedictine monks at Hamble Le Rice by the 12th century. These monks came from the Abbey of Tiron in France. (Images below by Tony Grant.)

Infirmary. Netley Abbey. Image Tony Grant.

Netley Abbey Ruins. Image Tony Grant

Archway. Netley Abbey. Image Tony Grant

In 1536 Henry VIII began the suppression of the monasteries in England. The destruction of the monasteries transformed the power and political structures in England. Henry had cut himself off from Rome and had made himself the head of the church in England. He destroyed the monastery system for the wealth they provided and also to suppress political opposition. The monasteries and the church had been a social and political force that in some ways had been more powerful than the monarchy itself. Church property in England had been home to 10,000 monks, nuns, friars and canons. Henry sold the land to landowners. Some of the buildings became churches of the church of England, such as Durham Cathedral. Many were left to ruin ,such as Tintern Abbey in the Wye Valley on the border of England and Wales. The monks who resisted were executed. The majority were pensioned off. Some of the funds Henry gathered were used to set up educational establishments, such as Trinity College Cambridge and Christ Church Oxford. One disastrous result from the dissolution of the monasteries was the destruction of entire monastic libraries, including the loss of many ancient music manuscripts.

The Abbey in the 18th and 19th centuries

Netley Abbey however, was not destroyed but given to Sir William Paulet as a reward for his loyal services. He’d held a number of high profile jobs, including the Treasurer to the Royal Household. Sir William turned the Abbey into a private mansion and reused many of the Abbeys existing buildings. The cloisters became a courtyard. He demolished the monk’s refectory and built an elaborate turreted entrance. The mansion remained inhabited until 1704 when the then owner started selling it off for building materials. The Tudor adaptations were mostly removed in the later 19th century, although sections of brickwork can be found within today’s remaining structure.

Netley Abbey. Image Tony Grant

The Tudors built with brick and these are the few remaining Tudor parts.

The Abbey’s Role in Gothic Revival Architecture

Horatio Walpole

Netley Abbey played an important role in the 18th and 19th century Gothic revival. Horace Walpole, the 4th earl of Orford, visited Netley Abbey on September 18th 1755. His original name was Horatio Walpole, (born Sept. 24, 1717, London—died March 2, 1797). He was the son of England’s first prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole. Horace Walpole was an English writer, connoisseur, and collector who was famous in his day for his medieval horror tale, The Castle of Otranto, published in 1764, which initiated the vogue for Gothic romances. He is remembered today as perhaps the most assiduous letter writer in the English language. Walpole wrote to his friend Richard Bentley. He had been staying with his friend, Chute, at The Vyne near Basingstoke. They had departed on a trip to visit Winchester and Southampton. While in Southampton they visited Netley Abbey. Walpole wrote:

“Mr Chute persuaded me to take a jaunt to Winchester and Netley Abbey with the latter of which he is very justly enchanted.”

In his letter, Walpole doesn’t seem to think much about Winchester, “it is a paltry town,” but he enthused about Netley Abbey.

“The ruins are vast, and retain fragments of beautiful fretted roofs pendent in the air, with all variety of Gothic patterns of windows wrapped round and round with ivy — many trees are sprouted up amongst the walls, and only want to be increased with cypresses! A hill rises above the abbey, encircled with wood: the fort, in which we would build a tower for habitation, remains with two small platforms. This little castle is buried from the abbey in a wood, in the very centre, on the edge of the hill: on each side breaks in the view of the Southampton sea, deep blue, glistering with silver and vessels; on one side terminated by Southampton, on the other by Calshot castle; and the Isle of Wight rising above the opposite hills. In short, they are not the ruins of Netley, but of Paradise.— Oh! the purple abbots, what a spot had they chosen to slumber in! The scene is so beautifully tranquil, yet so lively, that they seem only to have retired into the world.”

Thomas Gray, English Poet

Thomas Gray

Horace Walpole goes on to mention that his friend Thomas Gray had visited Netley previously. Gray had written a letter about his visit to Netley to the Rev. N. Nichols:

“Monday, 19th November 1764.

In the bosom of the woods (concealed from profane eyes) lie hid the ruins of Netley Abbey. There may be richer and greater houses of religion, but the abbot is content with his situation. See there, at the top of that hanging meadow under the shade of those old trees that bend into half a circle about it, he is walking slowly (good man!) and bidding his beads for the souls of his benefactors interred in that venerable pile that lies beneath him. Beyond it (the meadow still descending) nods a thicket of oaks, that mask the building and have excluded a view too garish and too luxuriant for a holy eye: only, on either hand, they leave an opening to the blue glittering sea. Did not you observe how, as that white sail shot by and was lost, he turned and crossed himself to drive the tempter from him that had thrown distraction in his way. I should tell you, that the ferryman who rowed me, a lusty young fellow, told me that he would not, for all the world, pass a night at the Abbey (there were such things seen near it), though there was a power of money hid there. From thence I went to Salisbury, Wilton, and Stonehenge; but of these things I say no more, they will be published at the University press.”

Thomas Gray (26 December 1716 – 30 July 1771) was an English poet, letter-writer, classical scholar, and professor at Pembroke College, Cambridge. He is widely known for his, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,”published in 1751.

Gray’s ,”Elegy written in a country churchyard,” was completed in 1750 and first published in 1751. The poem was completed when Gray was living near St Giles’ parish church at Stoke Poges. It was sent to his friend Horace Walpole, who popularised the poem among London literary circles. Here is an extract that might evoke the atmosphere of Netley.

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd wind slowly o’er the lea,

The plowman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

Now fades the glimm’ring landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds;

Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tow’r

The moping owl does to the moon complain

Of such, as wand’ring near her secret bow’r,

Molest her ancient solitary reign.

John Constable

John Constable

John Constable, 1776 – 1837, is famous for his landscapes, which are mostly of the Suffolk countryside, where he was born and lived. He made many open-air sketches, using these as a basis for his large exhibition paintings, which were worked up in the studio. His pictures are popular today, but they were not well received in England during his lifetime. His most famous pictures include ,”The Hay Wain,” and a series of paintings, sketches and drawings of Salisbury Cathedral from the water meadows. He painted many pictures in the area of East Bergholt, Suffolk, where he was born and brought up.

Constable and his wife visited Netley Abbey, Hampshire on their honeymoon in 1816. One of the drawings made on that occasion was the basis for this much later watercolour.

Constable Painting of Netley Abbey, Tate Gallery

It resembles the designs Constable painted in 1833 to illustrate an edition of Gray’s ‘Elegy.’

George Keate

George Keate, another visitor to Netley Abbey, was born on 30 November 1729 at Trowbridge in Wiltshire, where his father had property. He was educated by the Rev. Richard Wooddeson of Kingston upon Thames, together with Gilbert Wakefield, William Hayley, Francis Maseres, and others.

On leaving school, Keate was articled as clerk to Robert Palmer, steward to the Duke of Bedford. He entered the Inner Temple in 1751, was called to the bar in 1753, and in 1791 was made bencher of his inn, but never practised the law. In 1850, when his mother died, he inherited his family’s money. For some years he lived abroad, mainly at Geneva, where he knew Voltaire. By 1755 he was in Rome. After settling in England, Keate, began to write. He was in turn poet, naturalist, antiquary, and artist. A founder member of the Society of Artists in 1761, he left it for the Royal Academy in 1768. Keate was elected Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London and Fellow of the Royal Society in 1766. In 1764 he wrote this poem about Netley Abbey entitled,

“The Ruins of Netley Abbey. A Poem.” Here is an extract.

More welcome far the Shades of this wild Wood

Skirting with cheerful Green the seabeat Sands,

Where NETLEY, near the Margin of the Flood

In lone Magnificence a Ruin stands.

How chang’d alas! from that rever’d Abode

Which spread in ancient Days so wide a Fame,

When votive Monks these sacred Pavements trod,

And swell’d each Echo with JEHOVAH’S Name!

Now sunk, deserted, and with Weeds o’ergrown,

Yon aged Walls their better Years bewail;

Low on the Ground their loftiest Spires are thrown,

And ev’ry Stone points out a moral Tale.

Mark how the Ivy with Luxuriance bends

Its winding Foliage through the cloister’d Space,

O’er the green Window’s mould’ring Height ascends,

And seems to clasp it with a fond Embrace.—

Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding

In 1826 Copeley Fielding visited Netley Abbey and produced this water colour.

Copeley Fielding Painting of Netley Abbey, Tate Gallery

Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding (22 November 1787 – 3 March 1855), commonly called Copley Fielding, was an English painter born in Sowerby, near Halifax, and famous for his watercolour landscapes. At an early age Fielding became a pupil of John Varley. In 1810 he became an associate exhibitor in the Old Water-colour Society, in 1813 a full member, and in 1831 President of that body (later known as the Royal Society of Watercolours), until his death.

In 1824, Copley Fielding won a gold medal at the Paris Salon alongside Richard Parkes Bonington and John Constable. He also engaged largely in teaching the art. He later moved to Park Crescent in Worthing and died in the town in March 1855.

Origins of Gothic Novels

Netley Abbey: A Gothic novel by Richard Warner, 1795

John Mullins, in an article about ,”The Origins of the Gothic,” published in 2014 for the British Library, writes,

“Gothic fiction began as a sophisticated joke. Horace Walpole first applied the ,”Gothic,”to a novel in the subtitle-“A Gothic Story,” – or, “The Castle of Otranto,” published in 1764. Mullins writes that when Walpole used the word Gothic he meant ,”barbarous,” as well as, “deriving from the middle ages.

Anne Radcliffe, Wikipedia Commons

In the 1790s novelists rediscovered what Walpole had imagined. Anne Radcliffe wrote The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) She created a brooding aristocratic villain, Montoni, who threatens the resourceful heroine Emily with an unspeakable fate. Radcliffe’s fiction was the natural target for Jane Austen’s satire, Northanger Abbey. Catherine Morland imposes her ,”Gothic,” thoughts and ideas on the real world of the Tilneys.”

Reading novels and novels of the Gothic genre especially are one of Catherine Morland’s greatest pleasures. When meeting her new friend Isabella Thorpe in the Pump Room, Isabella enquires why Catherine is late.

”But my dearest Catherine what have you been doing with yourself all this morning? Have you gone on with Udolpho?”

Catherine had and they began to discuss the plot.

“… and when you have finished Udolpho, we will read the Italian together; and I have made out a list of ten or twelve more of the same kind for you.”

These ”same kind” included, Castle of Wolfenbebavch, Clermont, Mysterious Warnings, Necromancer of the Black Forest, Midnight Bell, Orphan of the Rhine and Horrid Mysteries. Actually the titles alone set a gloomy mysterious dark mood. The enthusiasm of Isabella and Catherine for these novels seem to be echoed by Jane Austen’s tense, breathlessness that emerges from her writing. Is there a tone of cynicism and ridicule too in their listing? Although Austen exaggerates the Gothic genre you can’t help thinking that she must have read all of these novels herself, how else would she know them? Her close mimicking of the genre in Northanger Abbey also points to the realization that she absorbed all the traits of the Gothic genre and was using those effects to her own great delight. I think Jane Austen loved the Gothic genre even as she seems to ridicule it. It was a guilty pleasure to her, perhaps.

Jane Austen – full circle from Netley and Southampton to Northanger Abbey

Jane Austen, watercolour by her sister Cassandra, National Portrait Gallery

In 1806, Jane Austen, her mother Cassandra, her sister Cassandra, her friend Martha Lloyd and her brother, Francis’s new bride, Mary Gibson moved into a house in Castle Square Southampton rented from Lord Landsdown. The previous year, 1805, George Austen her father had died in Bath. Her mother, herself and her sister were in straightened circumstances. They had to rely quite heavily on Jane’s brothers for support. Francis was to be away at sea and his new bride, Mary, was already pregnant. She needed the support of the women in the family. Francis was to sail from Portsmouth but being a naval port it was not entirely suitable for his new wife, and his mother and sisters. Southampton, nineteen miles along the coast, was far more genteel.

The Austens knew Southampton and the surrounding areas well. Jane had visited Southampton on a number of occasions before moving there again in 1806. The family would often take trips into the surrounding areas, going to Beaulieu in the New Forest or take boat trips to the Isle of Wight. They would also go by rowing boat from The Itchen Ferry to Netley. Jane writing to Cassandra from Castle Square on Tuesday 25th October 1808,

“ We had a little water party yesterday; I and my two nephews went from the Itchen Ferry up to Northam, where we landed, looked into the 74, and walked home, and it was so much enjoyed that I intend to take them to Netley today; the tide is just right for our going immediately after noonshine but I am afraid there will be rain.”

Edward and George, Jane’s brother Edward’s boys, were staying with Jane at Castle Square. Their mother had died and they were receiving letters from their father about what was to happen. Both boys were naturally upset and Jane took their wellbeing into hand. She appears to have been quite successful keeping the boys occupied with a series of adventures. Netley Abbey must have had an effect on Austen. The Abbey had influenced novelists, poets and artists. Horace Walpole, the originator of the Gothic form, had been impressed by it. We can surmise that her visit to Netley Abbey influenced Jane’s reading of the Gothic novels and so influenced her writing of Northanger Abbey. Or perhaps her fondness for reading Gothic novels influenced her visit to Netley Abbey. It was, after all, a well-known beauty spot.

Northanger Abbey/Persuasion title page, Wikipedia Commons

Northanger Abbey was ready for publication in 1803 but was not published until December 1817 after Jane’s death in July of that year. From the tone of the letter, we can gather Netley was a well-known place to the Austen family. Prior to 1806, Jane had previously lived or stayed in Southampton: In 1783, when Mrs Crawley moved her school to Southampton from Reading; and also in 1793 at the age of 17 to stay with a cousin, Elizabeth Butler Harris, née Austen. Jane celebrated her 18th birthday at a ball at the Dolphin Hotel in Southampton High Street. She may well have been introduced to Netley Abbey on either of those occasions.

Whether Netley Abbey had an influence on Jane’s writing of Northanger Abbey or not, it was a place that had an influence on those connected with the Gothic movement.

Here is a description of Catherine Moorland experiencing Northanger Abbey at night.

“The night was stormy; the wind had been rising at intervals the whole afternoon; and by the time the party broke up, it blew and rained violently. Catherine, as she crossed the hall, listened to the tempest with sensations of aw; and, when she heard it rage round a corner of the ancient building and close with sudden fury a distant door, felt for the firs time that she was really in an Abbey.- Yes, these were characteristic sounds;- they brought to her recollection a countless variety of dreadful situations and horrid scenes, which such buildings had witnessed….”

Bibliography:

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen, first published 1818, (Penguin Classic 2006.)

Jane Austen’s Letters New Edition) Collected and edited by Deirdre Le Faye Third Edition 1995 Oxford University Press.

Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding 1787–1855 biography TATE BRITAIN

John Constable 1776–1837 biography TATE BRITAIN

Horace Walpole TO RICHARD BENTLEY, ESQ. Strawberry Hill, September 18, 1755.

George Keate: Wikipaedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Keate

Netley Abbey English Heritage.

”The Origins of the Gothic,” John Mullins published in 2014 for the British Library.

Read Full Post »

BTW, I noticed on Susan’s sidebar a saying that I keep in my office. Sisters always have a way of finding each other!!

BTW, I noticed on Susan’s sidebar a saying that I keep in my office. Sisters always have a way of finding each other!!