It will, I believe, be everywhere found, that as the clergy are, or are not what they ought to be, so are the rest of the nation.”—Edmund Bertram in Mansfield Park

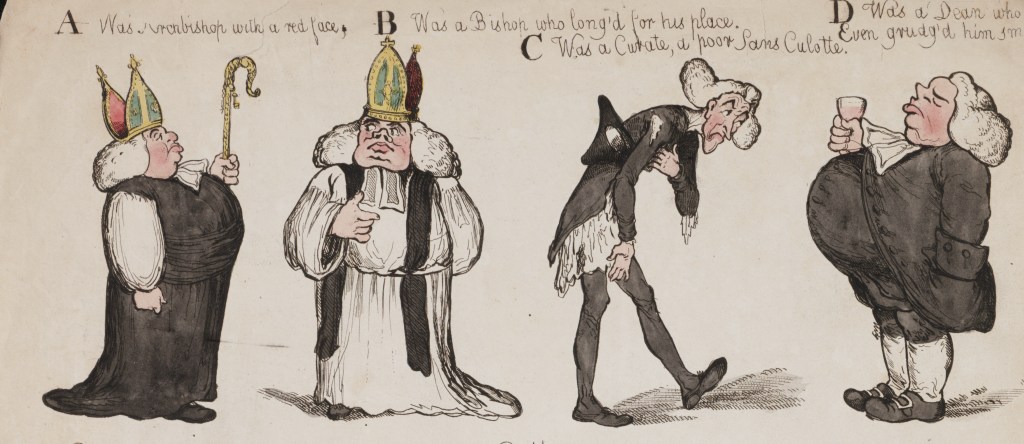

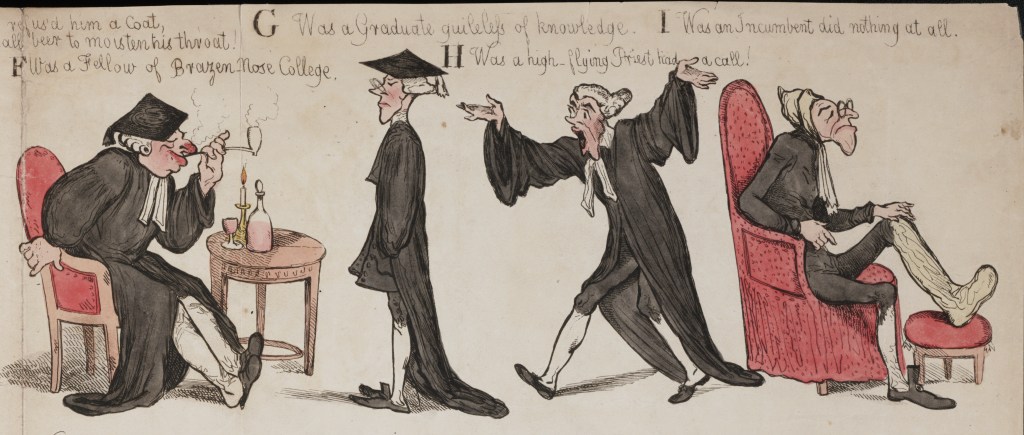

Richard Newton’s “Clerical Alphabet” satirizes the English clergy of Austen’s time. You may be familiar with cartoonists, or caricaturists, of the eighteenth century like Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray. Some of Rowlandson’s cartoons are based on Richard Newton’s work. Newton’s popular cartoons mocked the “establishment,” including fashions, politicians, the king, and even the church. Newton lived only 21 years. He died of typhus in 1798, shortly after he drew a satirical series on death!

Jane Austen herself wrote satirically, though much more gently, of the clergy. We laugh with her at foolish Mr. Collins, presumptuous Mr. Elton, and gluttonous Dr. Grant. It seems, though, that they performed their jobs as ministers adequately. In Emma, Miss Nash has copied down all the texts (Bible passages) Mr. Elton preached from since he came to Highbury. In Mansfield Park, Mary Crawford says Dr. Grant’s curate does much of his work. But at least Dr. Grant preaches good sermons, according to both Mary and Fanny Price.

Three of Jane Austen’s heroes, Edmund Bertram, Edward Ferrars, and Henry Tilney are conscientious clergymen. Sense and Sensibility tells us of Edward’s “ready discharge of his duties in every particular,” meaning that he willingly and eagerly did all that a clergyman was supposed to do. Henry Tilney employs a curate to do his duties while he is at Bath and Northanger Abbey. But Henry faithfully attends parish meetings, and I think he would have done his duties well once he was full-time at Woodston.

What were the clergy (church ministers or pastors) really like in Austen’s England? Many were good men, serving God and their communities. Jane’s father and brothers and her cousin Edward Cooper were faithful clergymen.

Mary Crawford of Mansfield Park, though, doesn’t think much of the clergy. “A clergyman is nothing,” she tells Edmund. Edmund and Fanny have much higher ideas of what the clergy can be, and should be.

Edmund says that the clergy “has the charge of all that is of the first importance to mankind, individually or collectively considered, temporally and eternally, . . . the guardianship of religion and morals, and consequently of the manners which result from their influence.” By “manners,” he explains that he means actions based on religious principles. He says the clergy have a huge influence on the people of their area.

Unfortunately, the church system in Austen’s day allowed anyone with a gentleman’s education and the right family and social connections to become a clergyman. Even an immoral man like Wickham could have been a clergyman, if he had not renounced his claim.

Newton’s cartoon shows us some of the major issues in Austen’s Church of England. Some of his clergymen are very fat and some are very thin. The church livings of Austen’s England were unevenly distributed. Some provided a high income, others a low income, and some were moderate. Let’s look in more detail at Newton’s criticisms of the Church of England in Jane Austen’s time, and how they connect to Austen’s novels.

The “Clerical Alphabet” begins:

A Was Archbishop with a red face,

B Was a Bishop who long’d for his place.

C Was a Curate, a poor Sans Culotte,

D Was a Dean who refus’d him a Coat

Even grudged him small beer to moisten his throat. (No picture for E, just a caption.)

A-B: In the Church of England, the king was the supreme authority of the church, and under him was the archbishop of Canterbury, then the archbishop of York. Each archbishop supervised a number of bishops, and the bishops supervised the more than 11,000 parish priests of England. Bishops and archbishops were wealthy men, with high incomes from the church. They were members of the House of Lords in Parliament. Mr. Collins says he is not worried that the archbishop or Lady Catherine will rebuke him for dancing. In reality, the archbishop would not know of Mr. Collins’s existence! Collins is exalting Lady Catherine by putting her at the same level as the highest church official.

C: Sans Culotte is French for “without pants” (more literally “without knee breeches”; the peasants wore long trousers instead of the knee breeches worn by upper classes). The “Sans Culotte” were the lower class French people who supported the French Revolution. In the English church, curates were the lowest rung of the clergy. Most lived on stipends of only £50 per year or less, barely enough for survival. They either assisted rectors and vicars, or led services in their place. In Persuasion, Mary Musgrove looks down on Charles Hayter as “nothing but a country curate.”

D-E: A dean was another wealthy church leader, the head clergyman overseeing a major church. In Mansfield Park, Mrs. Grant says they can move to London if someone commends “Dr. Grant to the deanery [the dean’s office] of Westminster or St. Paul’s.” Dr. Grant does get such a promotion at the end of the book. However, his gluttony kills him. No doubt this is Jane Austen’s own satire of wealthy clergymen!

Small beer was cheap beer with a low alcohol content. The church was not generous to the poor curates.

F Was a Fellow of Brazen-Nose College

G Was a Graduate guileless of knowledge

H Was a high-flying Priest had a call!

I Was an Incumbent did nothing at all.

F: Brazen-Nose College is a pun on Brasenose College of Oxford University. Fellows were the senior members of a college, usually clergymen. This one enjoys his pipe and his wine.

G: The graduate, without knowledge, is likely a member of the highest social classes. The nobility and others with wealth could graduate from Oxford or Cambridge University simply by being there for a certain amount of time. Students who were not as rich had to write essays in Latin and take exams. Clergymen followed the same course of study as any other gentlemen, plus they had to show up for one course on theology. Edward Ferrars says he was “properly idle” at Oxford.

H: The clergy was considered an occupation at this time, not usually a calling from God.

I: Once a man had a church living (a post as rector or vicar of a parish), he was the incumbent. He held the living until he died. In old age, or if he moved elsewhere, he would hire a curate to perform his duties. Although Dr. Grant gets a post at Westminster and moves to London, he still has the income from the parish of Mansfield Park (he is still the incumbent) until he dies. Then Edmund can take that parish.

(At this time, I and J were considered to be the same letter. So there is no J in this alphabet. That is also why the Jane Austen sampler has an I but no J.)

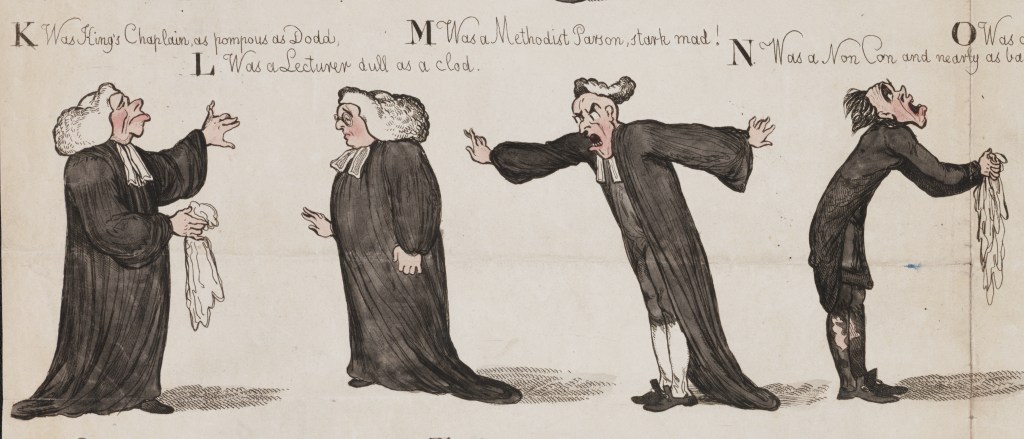

K Was King’s Chaplain as pompous as Dodd,

L Was a Lecturer dull as a clod.

M Was a Methodist Parson, stark mad!

N Was a NonCon and nearly as bad.

K: The king’s chaplain was the king’s personal priest for the Chapel Royal. William Dodd (1729-1777) was an extravagant clergyman who became chaplain to the King of England in 1763. To clear his debts, he forged a bond for £4200. He was convicted and hanged in 1777.

L: A lecturer was a preacher chosen and paid by the congregation who gave additional sermons (“lectures”) at a church, usually at afternoon or evening services.

M: The Methodists were part of the Church of England until around this time. They were known for their emotional enthusiasm and their focus on salvation by grace. Some Methodist preachers, including John Wesley, preached to large open-air meetings. According to Wesley’s Journal, listeners sometimes responded with “outcries, convulsions, visions, and trances.” More orthodox Anglicans considered this madness. When Edmund rebukes Mary Crawford, she ridicules him, saying, “when I hear of you next, it may be as a celebrated preacher in some great society of Methodists.” In the late 1700s, the Methodists separated from the Church of England and became Dissenters.

N: A NonCon was a Non-Conformist or Dissenter, a person who did not “conform” to the Church of England (or “dissented” from its statement of faith). These included Catholics, who faced major prejudices in Austen’s England. Baptists, Quakers, Independents, Unitarians, and others all fell into this category. They were usually from the middle and lower classes at this time. They could not get a degree from the universities, and were not supposed to hold public office. Mainstream Anglicans thought Nonconformists were enthusiasts (excessively emotional) like the Methodists.

O Was an Orator, stupid and sad.

P Was a Pluralist ever a-craving

Q A queer Parson at Pluralists raving!

O: An orator, as today, was a public speaker. In Mansfield Park, Edmund and Henry Crawford discuss how to best read the liturgy and preach in Church of England services. They agree that it was often done poorly. Edmund says that things have changed, and now, “It is felt that distinctness and energy may have weight in recommending the most solid truths.” Edmund is concerned with communicating truth. Henry, though, would like to speak well in order to be popular and admired.

P-Q: Pluralists held multiple church livings. They might live in one parish and serve as its minister and pay curates to serve the others, while they took most of the income from those parishes as well. They were not necessarily fat, though. Some livings were quite small and the clergyman needed a second one. Jane Austen’s father held two livings, at Steventon and Deane. They were close enough together that he could lead services at both churches on Sundays, and the income from each was low. Some pluralists, however, were extremely wealthy. In Mansfield Park, Sir Thomas Bertram says a clergyman should reside in his parish to set an example and care for the people of the parish. We don’t know what Edmund did once he had two parishes to care for, at Mansfield Park and Thornton Lacey.

R Was a Rector at Pray’rs went to sleep

S Was his Shepherd who fleec’d all his sheep.

T Was a Tutor, a dull Pedagogue

U Was an Usher delighted to flog.

R: Mr. Collins was quite proud of being a rector. The rector received all the tithes from the parish; a vicar like Mr. Elton only received a portion of the tithes.

S: This is a play on words. The clergyman was to be a shepherd, caring for his parishioners, his flock. However, he also had to collect tithes from them: one-tenth of their farm income, including crops, the young of animals, and even eggs from their poultry.

T: At Oxford, each student had a tutor responsible for his education. The tutor gave assignments and lectured. A pedagogue is a teacher, especially a pompous or strict one.

U: An usher was an assistant to a schoolmaster. Schools were often run by clergymen. Flogging, or whipping, was a common punishment.

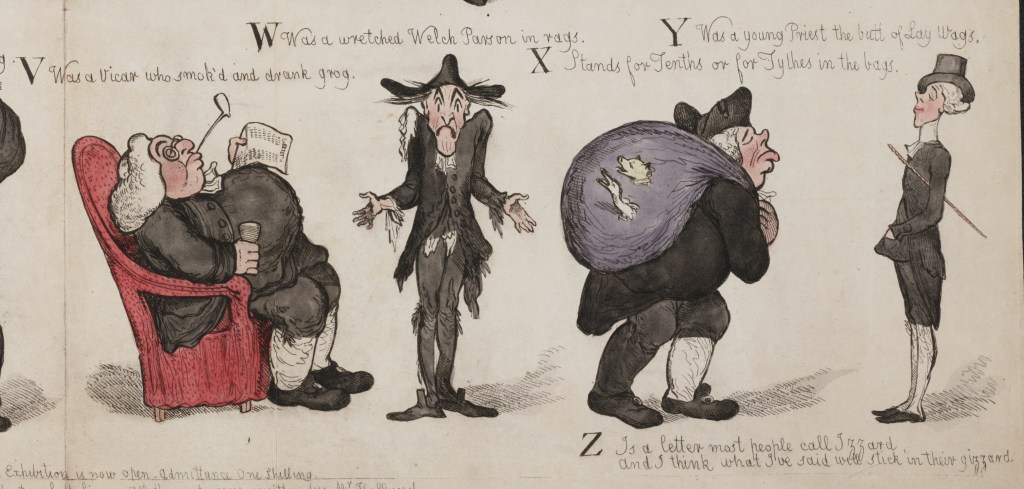

V Was a Vicar who smok’d and drank grog.

W Was a wretched Welch Parson in rags.

X Stands for Tenths or for Tythes in the bags.

Y Was a young Priest the butt of Lay Wags.

Z Is a letter most people call Izzard

And I think what I’ve said will stick in their gizzard. (No picture for Z.)

V: A vicar, like Mr. Elton, was a clergyman who only got about a quarter of the tithes for the parish; someone else, often the squire, received the rest. Drunkenness was a widespread issue in Austen’s England. Grog was an alcoholic drink, usually rum and water. It was usually associated with sailors.

W: The church in Wales was poor compared to the church in England.

X: The clergy’s main income came from tithes, collected from farmers in the parish (see S). People of the parish were legally required to pay tithes to the clergyman, even if they were Dissenters. This sometimes caused friction between clergymen and the people of the parish.

Y: Laymen, who were not clergy, made fun of this priest. Johnson’s Dictionary says a wag is anyone “ludicrously mischievous.” The cartoonist Newton himself was apparently one of these “lay wags” making fun of priests.

Z: Izzard is a dialectal word for z, first recorded about 1726. Newton wasn’t afraid to irritate his readers.

Do any of these clergymen remind you of characters in Austen’s novels? I think Dr. Grant might have become the fat dean if he had lived long enough. Mr. Collins might end up as the dozing rector. And Collins wanted to be a pluralist; he hoped for more livings from Lady Catherine.

This was obviously an exaggerated picture of the church in Austen’s England. Because of such clergymen who abused their positions, though, many people like Mary Crawford thought poorly of the church and the clergy. The cartoon points out some of the issues that later generations would correct.

About the author: Brenda S. Cox blogs on Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen, and is working on a book entitled Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England.

The British Museum www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG40122 offers brief information about Newton and a link to Newton’s many caricatures held by the British Museum. For more about Richard Newton and his life and cartoons, see Lambiek.

Inquiring readers,

Inquiring readers, ![1_P1040161_WINCHESTER_CATHEDRAL[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/1_p1040161_winchester_cathedral1.jpg)

![2_P1030843_nave[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2_p1030843_nave1.jpg)

![3_P1040022_grave_with_3_flowers[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/3_p1040022_grave_with_3_flowers1.jpg)

![4_P1040007_website_with_bust[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/4_p1040007_website_with_bust1.jpg)

![5_P1040041_website_signing_memory_book[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/5_p1040041_website_signing_memory_book1.jpg)

![6_P1040146_college_street[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/6_p1040146_college_street1.jpg)

![7_P1040139_website_nancy_at_front_door[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/7_p1040139_website_nancy_at_front_door1.jpg)

![8_P1040106_website_dog_close_up[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/8_p1040106_website_dog_close_up1.jpg)

![9_P1040124_website_film_crew[1]](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/9_p1040124_website_film_crew1.jpg)