Inquiring readers: I have no doubt you shall enjoy this review of Georgette Heyer’s The Masqueraders by my good friend, Lady Anne, an expert when it comes to the subject of this author. Lady Anne has read Georgette Heyer’s novels for most of her years upon this earth. Smart, sassy, fabulous, well tressed and well dressed, she has read every GH book backwards and forwards. There is not one tiny detail of Georgette’s novels that escapes Lady Anne’s attention or opinion. As to her review of The Masqueraders– please enjoy. For first-time readers: Spoiler alert.

Their infamous adventurer father has taught Prudence Tremaine and her brother Robin to be masters of disguise. Ending up on the wrong side of the Jacobite rebellion, brother and sister flee to London, Prudence pretending to be a dashing young buck, and Robin a lovely young lady…

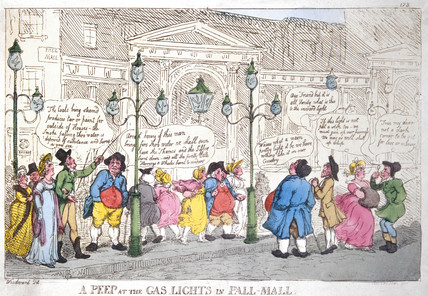

Although we know her as the queen of the Regency Romance, in fact, many of Georgette Heyer’s books take place a half-century or so earlier in Georgian times, with its gorgeous clothes, stylized social occasions, and convoluted intrigues. The Masqueraders could be set in no other time; it requires both the artifice and the intrigue to work.

We first meet the brother and sister, Robin and Prudence, in their elaborately contrived costumes; Robin disguised as the elegant and enchanting Kate Merriot, and Prudence, appearing as Kate’s equally elegant, if somewhat more retiring, brother Peter. They are on their way to London, to settle with a family friend and await the arrival of their father. The reason for the disguise is simple: Robin and his father backed the Stuarts in the 1745 uprising, and there is a price on each of their heads. But the reason they are indulging in this amazing masquerade of switched genders is due to their father, who has led them a precarious and wildly improper upbringing through most of the major cities of Europe. The old gentleman, as their not entirely dutiful children refer to him, married their mother, a farmer’s daughter, against his family’s wishes and left England without a backwards glance. But there is more mystery here, and the return to England in this fantastical make-believe plays into it.

In the opening chapter, the brother and sister meet an enchanting young lady who had wished for some excitement in her life ,but turned to the wrong person. Kate and Peter rescue her, and shortly after that delightful bit of playacting and sabotage, Sir Anthony Fanshawe, a close friend of Miss Letitia’s father, appears. Letitia becomes great friends with the lovely Kate, who in his real person is on his way to falling in love with the young lady. Sir Anthony also takes a shine to the attractive young man, who is so surprisingly worldly and well traveled, if slightly too smooth of cheek. We watch these circuitous wooings with delight; the young lady is all unaware, but what of Sir Anthony? He is a large man in his mid-30s, said by many to be sleepy, if not altogether dull, and slow to quarrel. But, large as he is, there is more to Tony Fanshawe than meets the eye. For several chapters, we wonder as Heyer walks a careful line; Sir Anthony is clearly interested in the young man, but before we start feeling any discomfort or seeing homoerotic overtones, we become aware that Fanshawe is not so sleepy, and he has ascertained the truth, not only behind Prudence’s masquerade, but also Robin’s, and perhaps as well, the mystery of the old gentleman. He asks if they had thought of what could have happened to Prudence had her identity been discovered by someone not in love with her. Such an occurrence had not been anticipated, and they wonder what had given her away:

“I should find it hard to tell you…some little things and the affection for her I discovered with myself. I wondered when I saw her tip wine down her arm at my card party, I confess.

My lord frowned, “Do you mean my daughter was clumsy?”

“By no means, sir. But I was watching her closer than she knew.”

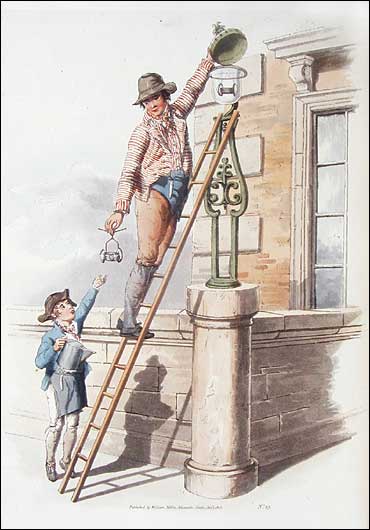

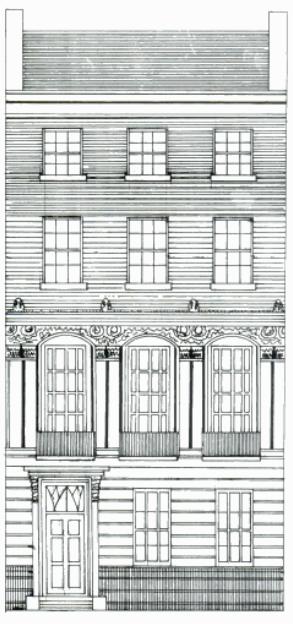

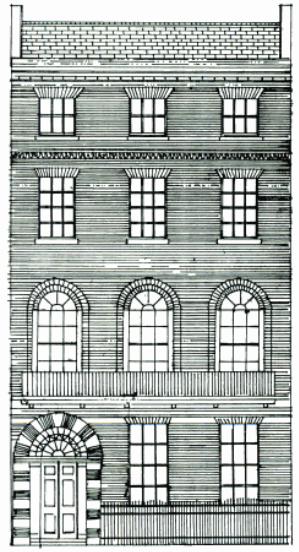

As the two romances work towards their happy conclusion, the larger story of the old gentleman, who he is really, and the place that he and his children will take in England plays out brilliantly. As is always the case in a Heyer historical novel, the times and the place are carefully laid out. The political fallout, the harsh measures taken against the Jacobites, and the dangers of living in London at that time all play their part in the plot, adding some weight, if not gravitas, to this fine caper. And too, there is great opportunity to enjoy several of Heyer’s delightful young gentlemen and their conversations among themselves. In fact, the stylized society that was so much of the mid-18th Century is what makes this plot work. Only in the elegant velvets and laces, the swordsticks and elaborate hairdos, long full petticoats, boots and full-skirted coats with fine gilt lacings could the brother and sister pull off their amazing disguises and the incredibly intricate plot unwind.

“I contrive,” said the old gentleman, and indeed he does. So too does his creator, in this charming tale of adventurers. The Masqueraders is a delightful romp from beginning to end, with one of the most romantic interludes, a ride in the moonlight, ever penned by this delightful and dependable author.

Other Georgette Heyer Book Reviews on this Site:

Gentle readers: Until Amazon.com stops strong arming publishers like McMillan about the pricing of their ebooks, I will not link to their site for book orders. Rather, I will link straight to the publisher’s site until the bullying tactics are resolved.