Today marks the start of a new series, in which I highlight several important events and details that happened in Jane Austen’s novels, letters, and lifetime during each month of the year.

We’ll kick off Jane Austen January (aka “Jane-uary”) by examining passages and situations in each of her novels that occur in January. While some of the novels have no mention of January, others do—with interesting results! Next, we’ll note where Austen was and what she was doing in January by checking her letters for January dates and details. Finally, we’ll highlight events and anniversaries that occurred in January that directed affected Jane Austen or her family.

All of this can help us better understand Austen’s life and times as we look at specific dates, events, and details in the context of months and seasons.

January in Regency Times

One of the highlights of January for Jane Austen’s family was surely Twelfth Night (also known as Epiphany), which falls on January 5th.

Maria Grace, in her article “Celebrating Twelfth Night–Jane in January and You,” explains its religious importance: “Epiphany or Twelfth Night … was the exciting climax of the Christmastide season… It was a feast day to mark the coming of the Magi bearing gifts to the Christ child, and as such was the traditional day to exchange gifts.”

She also explains the social side of Twelfth Night: “In Jane Austen’s day, the party of the year would generally be held on Twelfth Night.” (Austen Variations)

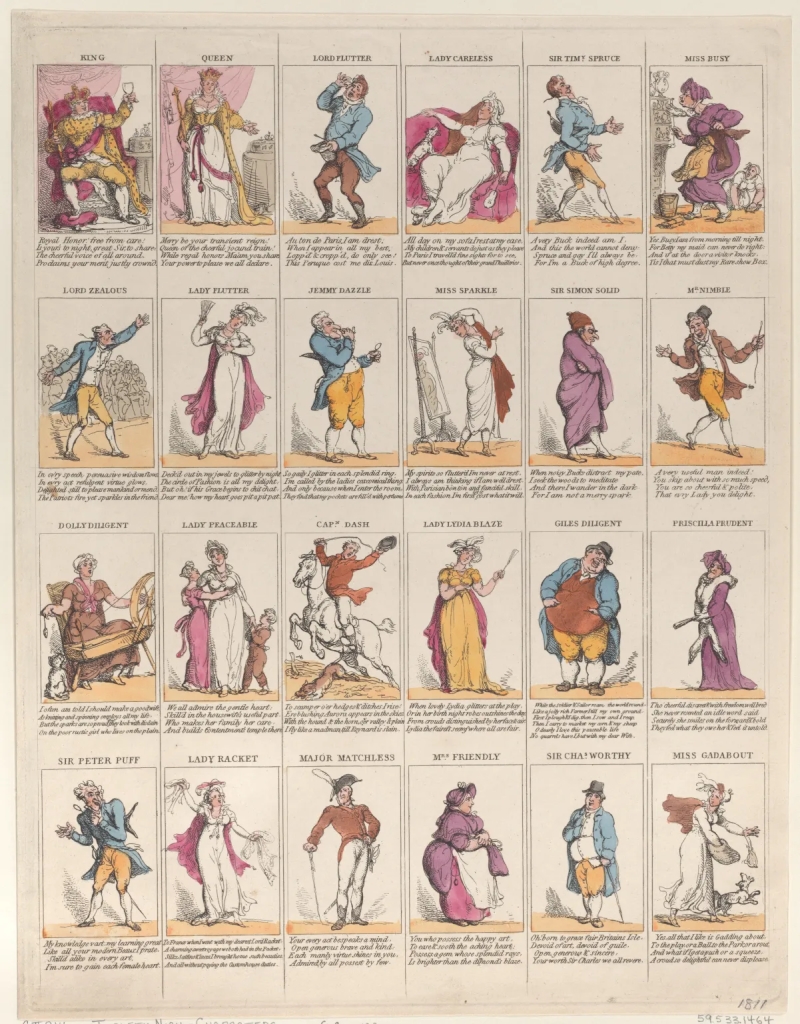

During the Regency Era, people hosted parties and balls to celebrate Christmas and especially the last day of the Christmas season. The entertainment often involved guests playing assigned parts for the evening, dressing up in costumes, eating “Twelfth Cake,” and eating and drinking.

In a letter to Cassandra on December 27, 1808, Austen writes about an upcoming ball between Christmas and “Twelfth-day” at Manydown:

I was happy to hear, chiefly for Anna’s sake, that a ball at Manydown was once more in agitation; it is called a child’s ball, and given by Mrs. Heathcote to Wm. Such was its beginning at least, but it will probably swell into something more. Edward was invited during his stay at Manydown, and it is to take place between this and Twelfth-day. Mrs. Hulbert has taken Anna a pair of white shoes on the occasion.

Austen’s Letters (December 27, 1808)

Later, on January 10, 1809, she writes, “The Manydown ball was a smaller thing than I expected, but it seems to have made Anna very happy. At her age it would not have done for me.”

January Travel in Jane Austen’s Novels

In Austen’s novels, January is primarily mentioned in the context of parties and travel. Anne Elliot goes to Bath for January and February, Miss Crawford is invited for “a long visit” to see her friend in London in January, Mrs. Jennings goes to her own house in London in January, and Mr. Bingley, Mr. Darcy, and Bingley’s sisters all go to London (when Bingley leaves Netherfield) and stay for the winter.

In Sense and Sensibility, Lucy Steele and her sister, Anne, go to “town” (London) in January to stay with relatives (and subsequently move from house to house throughout the season as socially advantageous opportunities become available):

I had quite depended upon meeting you there. Anne and me are to go the latter end of January to some relations who have been wanting us to visit them these several years! But I only go for the sake of seeing Edward. He will be there in February, otherwise London would have no charms for me; I have not spirits for it.

Sense and Sensibility

Mrs. Jennings, who “resided every winter in a house in one of the streets near Portman Square,” invites Elinor and Marianne to come with her to London in January when her thoughts begin to turn toward home after Christmas.

The London Season

So why do so many of Austen’s characters travel to London in January? Wouldn’t the weather make travel difficult? Wouldn’t they prefer to stay home (and inside) where it’s cozy?

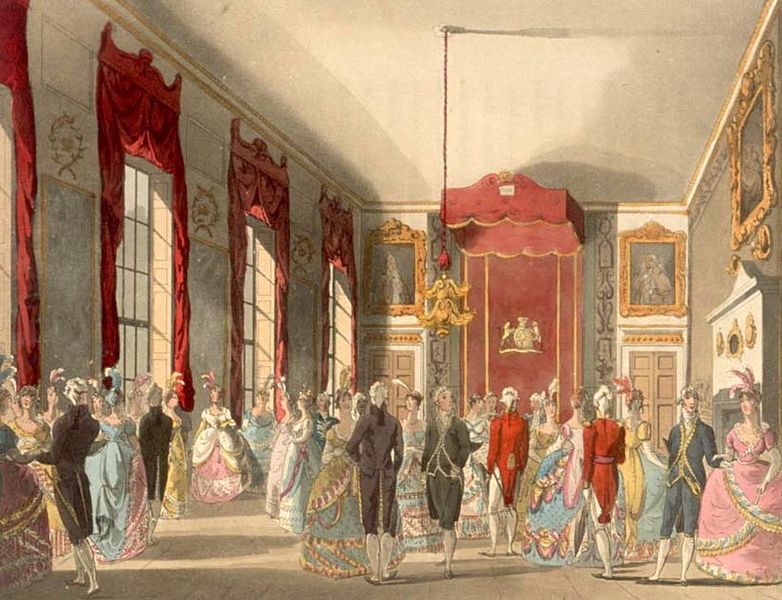

These are fair questions, but after Christmas, a large portion of the genteel class moved “to town” during the winter months for the London Season, which coincided with England’s political schedule, for entertainment and socializing. The Season had previously started in the fall, meaning most people went to London before the bad weather set in, but with the improvement of roads and travel during Austen’s day, the season slowly shifted later.

Here’s an explanation of the London Season from Jane Austen’s House Museum:

The London season coincided with the sitting of Parliament, beginning at some point after Christmas when fashionable families would move into their London houses. The men would attend Parliament, whilst the women shopped, visited, and found husbands for themselves or their daughters. It lasted until early summer, when the ‘beau monde’ would return to their country estates, escaping the city’s stifling heat and pungent smells.

The Season, Jane Austen’s House Museum

The season was a whirlwind of court balls and concerts, private balls and dances, parties and sporting events. On a typical day, ladies would rise early to go riding in Hyde Park, before returning home to breakfast and spending the day shopping, dealing with correspondence and paying calls.

Most villages had assemblies and balls during the winter, but all of the most important social occasions happened “in town.” In Pride and Prejudice, we’re told that the Bennet sisters have little to do “beyond the walks to Meryton” in January and February, when conditions are “sometimes dirty and sometimes cold” (Ch. 27). It makes sense that many young women longed to go to town in the winter, at the height of the London Season and “marriage market,” when the majority of the parties, balls, and social events were held.

January in Jane Austen’s Letters

January often brings rain, cold weather, and even snow to the various locations where Austen lived and traveled. Austen kept her spirits up, but January in England, especially in homes without central heating or today’s insulation, could not have been entirely comfortable. Balls and assemblies, visits and travel, kept Austen busy and content during the winter months.

Austen’s entries follow below and give us a glimpse into the miserable weather conditions during one particularly snowy and wet January:

17 January 1809 (Castle Square):

“Yes, we have got another fall of snow, and are very dreadful; everything seems to turn to snow this winter.”

24 January 1809 (Castle Square):

“This day three weeks you are to be in London, and I wish you better weather; not but that you may have worse, for we have now nothing but ceaseless snow or rain and insufferable dirt to complain of; no tempestuous winds nor severity of cold. Since I wrote last we have had something of each, but it is not genteel to rip up old grievances.”

In the same letter, Austen describes her writing:

“I am gratified by her having pleasure in what I write, but I wish the knowledge of my being exposed to her discerning criticism may not hurt my style, by inducing too great a solicitude. I begin already to weigh my words and sentences more than I did, and am looking about for a sentiment, an illustration, or a metaphor in every corner of the room. Could my ideas flow as fast as the rain in the store-closet, it would be charming.”

On the topic of the store-closet, she writes this:

“We have been in two or three dreadful states within the last week, from the melting of the snow, etc., and the contest between us and the closet has now ended in our defeat. I have been obliged to move almost everything out of it, and leave it to splash itself as it likes.”

30 January 1809 (Castle Square):

“Here is such a wet day as never was seen. I wish the poor little girls had better weather for their journey; they must amuse themselves with watching the raindrops down the windows. Sackree, I suppose, feels quite broken-hearted. I cannot have done with the weather without observing how delightfully mild it is; I am sure Fanny must enjoy it with us. Yesterday was a very blowing day; we got to church, however, which we had not been able to do for two Sundays before.”

And a final update on the flooded closet:

“The store-closet, I hope, will never do so again, for much of the evil is proved to have proceeded from the gutter being choked up, and we have had it cleared. We had reason to rejoice in the child’s absence at the time of the thaw, for the nursery was not habitable. We hear of similar disasters from almost everybody.”

If you’ve ever dealt with water damage or burst pipes due to cold weather, you know how awful and destructive it can be. Austen makes light, but one can imagine it caused quite a bit of damage.

January in Jane Austen’s Lifetime

And finally, let us turn our attention to some of the most important dates and events that happened (or were celebrated) during the first month of the year in Jane Austen’s lifetime. In December 1800, Reverend Austen decided to retire and remove his family to Bath. Austen’s letters in January 1801 prove an interesting read as she and the Austen family prepare to move later in the year:

3 January 1801 (Steventon):

Austen writes that her mother wants to keep two maids and quips about their plans to have “a steady cook and a young giddy housemaid, with a sedate, middle-aged man, who is to undertake the double office of husband to the former and sweetheart to the latter.”

Austen discusses three parts of Bath where they might live:

“Westgate Buildings, Charles Street, and some of the short streets leading from Laura Place or Pulteney Street.” She writes extensively about each neighborhood and several others, giving her opinion and hopes about each. She details which pictures, furniture, and beds they are choosing to keep or leave behind and asks Cassandra’s advice. And she shares plans for the family to travel to Bath a few weeks from then.

Austen shares own thoughts on their move to Bath:

“I get more and more reconciled to the idea of our removal. We have lived long enough in this neighborhood: the Basingstoke balls are certainly on the decline, there is something interesting in the bustle of going away, and the prospect of spending future summers by the sea or in Wales is very delightful. For a time we shall now possess many of the advantages which I have often thought of with envy in the wives of sailors or soldiers. It must not be generally known, however, that I am not sacrificing a great deal in quitting the country, or I can expect to inspire no tenderness, no interest, in those we leave behind…”

The letter is full of useful information and well-worth a read. You can access it HERE.

14 January 1801 (Steventon):

Austen speaks of the many visitors they’ve received in response to the news that Rev. Austen is retiring and the family is moving to Bath. She says, “Hardly a day passes in which we do not have some visitor or other: yesterday came Mrs. Bramstone, who is very sorry that she is to lose us, and afterwards Mr. Holder, who was shut up for an hour with my father and James in a most awful manner.”

January Dates of Importance

This brings us now to several dates that would have been quite important to Austen personally:

Celebrations/Birthdays:

9 January 1773: Jane Austen’s sister, Cassandra Elizabeth Austen, born.

23 January 1793: Edward Austen’s first child, Fanny, born.

Goodbyes/Sorrows:

January 1796: Tom Lefroy leaves Ashe for London (and never returns) and Tom Fowle (Cassandra’s fiancé) sets sail for the Indies, where he later dies.

21 January 1805: Rev. George Austen (Jane’s father) dies suddenly in Bath.

Writing:

28 January 1813: Pride and Prejudice was published, by Thomas Egerton (Whitehall, London).

21 January 1814: Austen begins writing Emma.

The Joys of Sleuthing

I hope you’ve enjoyed this first installment of our month-by-month exploration of Jane Austen’s world. I was pleasantly surprised to find that there was so much more to research and explore about the month of January than I anticipated. I enjoyed sleuthing around, following my nose, and discovering what I could uncover–just with the word “January.” If I’ve missed anything major related to January, or if you have ideas about what I might pursue for February, please share it in the comments. It takes a village with this type of research!

RACHEL DODGE teaches college English classes, gives talks at libraries, teas, and book clubs, and writes for Jane Austen’s World blog. She is the bestselling author of The Little Women Devotional, The Anne of Green Gables Devotional and Praying with Jane: 31 Days Through the Prayers of Jane Austen. Now Available: The Secret Garden Devotional! You can visit Rachel online at www.RachelDodge.com.