Over a year ago I read a fabulous blog post on the Regency Redingote entitled Boy to Man: The Breeching Ceremony. The article is thorough and I was quite satisfied with its information until I ran into this quote, written by Jane Austen in 1801 to her sister Cassandra:

Mary has likewise a message: she will be much obliged to you if you can bring her the pattern of the jacket and trousers, or whatever it is that Elizabeth’s boys wear when they are first put into breeches; so if you could bring her an old suit itself, she would be very glad, but that I suppose is hardly done.”

This short passage told me much more about the topic and I decided to pursue it further.

Portrait of William Ellis Gosling, 1800 , Sir William Beechey, R.A. Image @Wikimedia Commons

During the 18th century boys and girls were dressed alike in baby clothes during their infancy and in petticoats as toddlers. In Beechey’s image, our modern eyes would not identify the infant as a boy unless he was labeled as such.

At some point, the boys** would be placed in skeleton suits or a form of pantaloons and a frilly tunic. Their hair was still worn long and they still lived in the nursery, if the household was wealthy enough, or were overseen by women – their mothers, older sisters, grandmothers, aunts, nursemaids, etc.

Fathers rarely stepped inside the nursery, the province of women. In this idealized scene, the infants are guided on leading strings and a special “cage” that enabled toddlers to learn to walk. Image, source unknown. (Does anyone know the provenance?)

Between the age of 4-6, they would have their hair shorn and graduate to wearing trousers. This important event was marked by a breeching ceremony, a significant milestone in a young boy’s life. I can liken it to my first communion at the age of six. It was an event so important and memorable that I can still vividly recall my pretty white dress and veil, and the details of receiving my first communion wafer and celebrating the occasion with close family and friends. I felt different after that day, and in that way can relate to the pride that 18th and 19th century boys must have felt as they changed into the clothes that marked their first step to manhood.

The modern eye would regard these two children as girls. Lydia Elizabeth Hoare (1786–1856), Lady Acland, with Her Two Sons, Thomas (1809–1898), Later 11th Bt, and Arthur (1811–1857)

by Thomas Lawrence

Date painted: 1814–1815. Image @National Trust Collection

The breeching ceremony had little to do with social status and was practiced across all class lines. The rich could afford any amount of new clothes for their children, made by tailors or seamstresses, no doubt, but at the start of the Industrial Revolution, the cost of clothing was still prohibitive for even the gentry, the class to which Jane Austen’s family belonged. As Jane Austen so often mentioned in her letters, clothes were generally remade and recycled rather than discarded. Ribbons, buttons, lace, or other embellishments were added to update a garment, and sleeves were reshaped or cut down to size, and hems raised or lengthened as current fashion required. If the garment was no longer suitable for one person, it could be cut down to size for someone who was smaller. The refashioned garment was worn and patched until it was given to the poor or used as rags.

Jane Austen’s comments about her sister-in-law’s request to Cassandra to bring back a pattern to share or an old suit for her boy’s breeching ceremony now makes sense. The women of the house sewed the clothes (for mass production of garments and textiles was still in the future), and shared patterns and borrowed sartorial ideas from each other. Hand me downs were de rigeur, I am sure, for most parents of that era with large families could scarcely afford new clothes for each of their many children.

Thomas Lawrence

English (Bristol, England 1769 – 1830 London, England)

Sir Walter James, Bt., and Charles Stewart Hardinge, 1829. Image @Harvard Art Museums

Regardless of social standing, all boys, even those from the lower sorts, would receive a new pair of breeches around the age of six (four to six, to be more precise). The breeching event provided a cause for private celebration, to which family and friends were invited. For the parents, this ceremony also acknowledged that their child had survived past infancy. In an age when so many children died before reaching their majority (almost a fourth of them would die before the age of 10), the breeching ceremony might well have been the only significant event in a young boy’s life. In addition, he received a set of brand new clothes – a milestone indeed!

To put a perspective on how a parent felt about this event, Samuel Taylor Coleridge proudly writes of his son Hartley’s breeching ceremony in 1801:

Hartley was breeched last Sunday — & looks far better than in his petticoats. He ran to & fro in a sort of dance to the Jingle of the Load of Money, that had been put in his breeches pockets; but he did [not] roll & tumble over and over in his old joyous way — No! it was an eager & solemn gladness, as if he felt it to be an awful aera in his Life. O bless him! bless him! bless him!” – Samuel Coleridge to Robert Southey, November 9, 1801

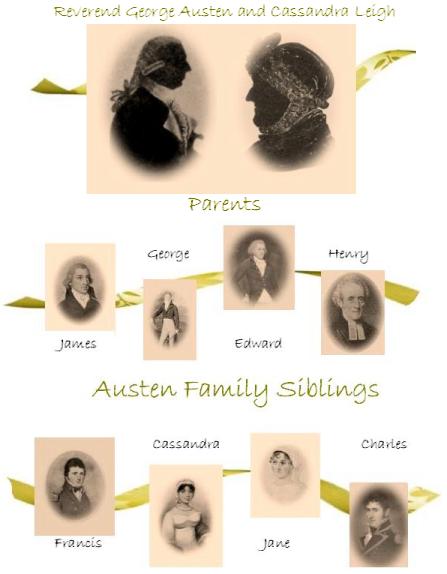

What a vivid description! Relatives and friends, including the godparents, showered the young boy with coins and gifts. This ceremony marked an important occasion in which the boy left the world of women (nursery). After this momentous event, his father would become more involved with his upbringing or he would be mentored by other men in his life. He might be placed in a nearby boarding school with the young sons of other gentry, such as the one that Rev. Austen ran, for example, or in a more prestigious school if his parents were richer. Opposed to a young boy of the same age, a little girl’s life remained essentially the same – she would learn the art of running a household and catching a suitable man, but her young male counterpart would learn the art of running an estate or, if he was a second son, the skills required to make his way in life. (Click here for a modern image of breeches.)

THE CHILDREN OF RICHARD CROFT, 6TH Bt.,c.1803, by John James Halls, R.A. In this image one can see the three stages of boyhood – petticoats, skeleton suit, and jacket, shirt, and trousers.

**The type of clothing that young boys wore after the breeching ceremony depended on the century. During the 17th century, children’s clothes looked like miniature versions of adults. Young boys wore waistcoats, shirts, breeches, stockings and leather shoes. But by the time Jane Austen and Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote their remarks in 1801, childhood was extended. Little boys wore skeleton suits until the age of nine, and then were graduated into more adult like clothing. Sons of the working class and poor did not wear skeleton suits, but wore clothing that resembled that of their farmer and laborer fathers.

More on the Topic:

- The Well-Dressed Regency Boy Wore a Skelton Suit on this blog

- Baby Jane Austen’s First Two Years on this blog

- The Conservation of Edward Austen Knight’s Childhood Suit: Chawton House Library on this blog

- Recommended reading: Boy to Man: The Breeching Ceremony

Other links and resources:

- What is Masculinity?, by John H. Arnold, Sean Brady, 2011

- Thicker Than Water: Siblings and Their Relations, 1780-1920, Leonore Davidoff, 2012

- Clothes and the Child: Handbook of Children’s Dress in England 1500-1900 by Anne Buck (Aug 27, 1996)

- Huck’s raft: a history of American childhood, By Steven Mintz