Inquiring Readers: This is the fourth and final post in honor of Pride and Prejudice Without Zombies, Austenprose’s in-depth reading of Pride and Prejudice, which is winding up this week.. My first post discussed Dressing for the Netherfield Ball, the second talked about the dances, and the third showcased the suppers that might have been served. This post discusses the music that was popular during Jane Austen’s era and that she personally liked. Some of her preferences are vastly different than those shown in film and tv productions.

“Yes, yes, we will have a pianoforte, as good a one as can be got for 30 guineas, and I will practice country dances, that we may have some amusement for our nephews and nieces, when we have the pleasure of their company.” – Jane Austen to Cassandra, 1808

Georgiana Darcy at her pianoforte

Like many ladies of her era, Jane Austen was an accomplished musician. And so were her characters. In Pride and Prejudice, Mary Bennet, Elizabeth Bennet, the Bingley sisters and Georgiana Darcy could all play instruments with skill. Lady Catherine de Bourgh would have been a proficient, as would her daughter Anne, had she learned and practiced. Before the age of electricity and cable the world was largely silent musically speaking, save for the music played by family members, local musicians, or more famous musicians who were paid to play for the rich.

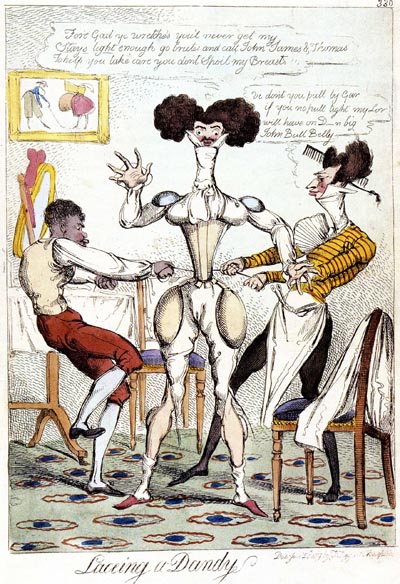

Street Music, 1789

Musicians wandered the land, and London streets offered a pandemonium of sounds, much of it derived from musical instruments. The only music available in the home was that which amateur or professional performers could produce on the spot, so that the ability to play music well was crucial for all walks of life. From childhood on, young ladies were expected to play a musical instrument and study with music masters. Gentlemen sang as well and formed impromptu amateur groups that entertained in taverns and men’s clubs.

Farmer Giles and his wife showing off their daughter Betty to their neighbors on her return from school, Gillray, 1806

In Pride and Prejudice, Mary Bennet, while considered technically skilled, was pendantic compared to her sister Elizabeth, whose musical style was more lively and who could sing with more expression. An evening in the Regency era might consist of a family gathered in the drawing room, with the women preoccupied with a household task like sewing, the men reading, or a group playing games, and someone playing a musical instrument or singing a popular song. For larger gatherings, small ensembles would form, prompting others to push furniture aside, roll up the carpet, and dance a jig or a reel, as I imagine Lydia Bennet and her friends might have done at Colonel Forster’s home. Sometimes professionals mixed with amateurs. In 1811, Jane Austen wrote about a get together at her brother Henry’s house in London:

George Woodward. "Savoyards of Fashion -- or, the Musical Mania of 1799.

“Above 80 people are invited for next Tuesday evening, and there is to be some very good music — five professionals, three of them glee singers, besides amateurs. Fanny will listen to this. One of the hirelings is a Capital on the harp, from which I expect great pleasure.”

Marianne Dashwood sings and plays

Like Anne Elliot in Persuasion, Jane Austen frequently played the pianoforte for the enjoyment of her family. She practiced several hours every morning before others in her family began their day. Her niece Caroline recalled her aunt as having a natural taste in music. Natural or not, Jane studied for several years with Dr. Chard, an organist at Winchester Cathedral. It was said that her speaking voice was as sweet as her singing, and that she sang for her family only. A place in Chawton Cottage was reserved for the piano forte (Marianne Dashwood had her gift from Colonel Brandon placed in the drawing room in Barton Cottage), but some of the larger homes in the Regency era might have a room dedicated solely for music. Georgiana Darcy played so well that her brother had an entire room made over for her music. These rooms would contain a variety of instruments, including the harp, flute, violin and pianoforte.

Playing in Parts, James Gillray

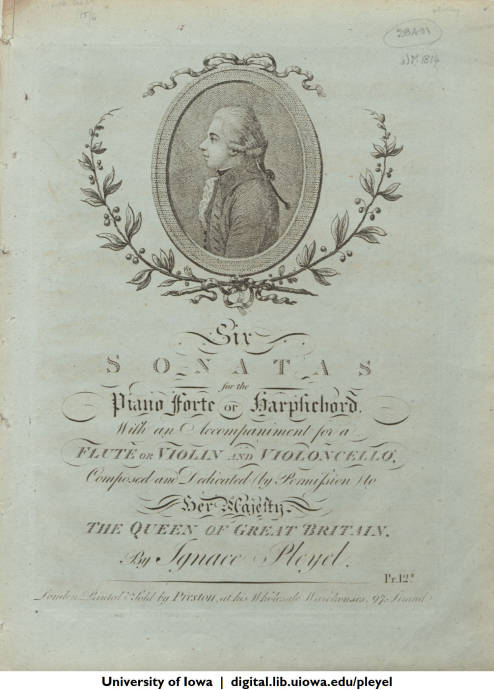

“Through most of the 19th century, the lines between ‘popular’ and classical music were much more blurred than they are today. A Regency musicale or parlor performance could include a traditional Irish air popularized by Thomas Moore, a piano sonata by Pleyel, a favorite song from a ballad opera, or a setting of a popular dance tune.” – Anthea Lawson

Jane’s musical preferences tended towards the songs and dances that were popular at the time. That some of yesteryear’s tunes have become today’s classical music (Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven) happened purely by chance, for many of the composers whose music and songs Jane Austen preferred have faded into obscurity. Jane favored Ignaz Pleyel over Haydn, and had included in her musical collection 14 of his sonatinas. She played folk songs, Scotch and Irish airs (many arranged by Haydn and Beethoven), and songs from the popular stage by such composers as Dibdin, Arne and Shiled. She also collected works from Piccinni, Sterkel, and J.C. Bach, and owned Steibelt’s ‘Grand Concerto, Haydn’s English Conzonets, glees music of John Wall Callcott, and Che Faro from Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice. ( Music: What Was Popular When Jane Austen Was Writing?)

A Little Music, Gillray, 1810

In Pride and Prejudice, Mary Bennet played a selection of Scotch and Irish airs, which were quite popular at the time. Jane Fairfax in Emma played Robin Adair, a tune by G. Kiallmark that Jane Austen must also have played, for there were several variations of the song in her folio collection of music.

Jane Austen's copy of Dibdins "The Soldiers Adieu." She altered soldier to sailor.

Purchasing music sheets was expensive during the Regency era. People would loan sheet music to each other,which they would then copy into notebooks. While Austen did not write the lyrics she sang, she did choose which music she wanted to play. After borrowing a piece, she painstakingly copied it into a notebook with pre-ruled paper, or assembled the pieces she purchased into albums. Today, The Chawton House Trust owns eight volumes of Jane Austen’s collection of sheet music, two of which were largely written in Jane’s hand. A third volume was also copied by someone’s hand, and “five volumes contain printed music of songs, keyboard works, and chamber music from a variety of sources.” – (The Gift of Music )

Pleyel sonatas for the pianoforte or harpsichord

About half of the music in Jane’s notebooks are for vocals, or folk songs that tell stories. A few are so comic and fun that it is logical that the author of Pride and Prejudice and The History of England would be attracted to them. Charles Dibdin a composer and performer much in the vein of Benny Hill, wrote “The Joys of the Country,” which Jane copied by hand. He also wrote more serious, sentimental, and patriotic songs, supporting the fact that Jane’s taste was eclectic. She copied out the Marseillaise as The Marseilles March, and owned 56 Scottish songs, like “O Waly Waly”. Jane compiled more than the eight music books that reside at the Chawton House Trust, but the additional books, once studied by scholars in the 1970s and 1980s, are no longer available for study. (- I burn with contempt for my foes – Jane Austen Music Collections .)

Robin Adair, Scots Melody, Caroline Keppel

“In the evening she would sometimes sing, to her own accompaniment, some simple old songs, the words and airs of which, now never heard, still linger in my memory.” (James Edward Austen Leigh Memoir 330)

Many of the songs that were popular during the Regency era were franker than the topics that ladies of the Regency were allowed to conduct in polite conversation. Scored for a soprano voice, these popular ditties spoke of love and pursuit, sexual invitation, and people declaring their love openly – “some sexually, some chastely, some sweetly, some comically, some sentimentally, some melodramatically–a wildly “forward” thing for ladies to do in speech but apparently not in song.” (- I burn with contempt for my foes – Jane Austen Music Collections .) Unmarried ladies sang songs in accents or impersonating Scottish girls. These musicales allowed them a freedom of expression and role playing that Jane Austen could have included in her novels. Many a chaste lady sang a bawdy song with an accent or impersonated a Scottish girl, with no one thinking the worst of her. (Jane Austen Music Collection.)

Ladies at the piano, early Regency period

The Turban’d Turk

“The London folks themselves beguile

And think they please in a capital stile

Yet let them ask as they cross the street

Of any young virgin they happen to meet

And I know she’ll say, from behind her Fan

That there’s none can love like an Irishman

Like an Irishman”

(The British Minstrel and National Melodist, p 265-266, Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper, 1827)

The Piano Lesson, Girard, 1810

Like record producers and composers today, music publishers issued thousands of new songs for vocal performance and music for dances per year. In 1790 Andrews and Birchall published sheet songs bearing their name. Besides these, the bulk of Andrews’s publications between 1804-1810 included a sseries of ” Five Favourite Dances,” folio, Numbers i to 39 (7, 8, and 9 dated 1805), and a small oblong volume for the flute ” The Gentleman’s Vade Mecum.” William Campbell published principally minor books dances, and include a series “Campbell’s Country Dances and Reels,” in oblong quarto. This runs to twenty seven books, and was re-issued, and probably continued from the 22nd up to this number by Robert Birchall. Werner was a dancing master and master of the ceremonies at Almack’s and the Festino Rooms. He lived at 6, Lower St. James’ Street, Golden Square, in 1782 and died in1787. Campbell, Fentum, Birchall, and Andrews, and others published his yearly books. When Jane traveled to London to visit her brother Henry, she haunted the shops, no doubt in search of new music as well as new fabrics, books, and gifts for the family.

Rowlandson, The Concert, Bath

During the 1790s the London concert life changed. Amateur orchestras in city taverns or in gentlemen’s clubs competedwith the professional concerts that began to sprout up in public places. (- The Rage for Music, Simon McVeigh) Local musicians would be hired for assembly balls in small towns. Musicians with a more professional background would be enlisted to play at more stylish events, like the Netherfield Ball. The lady asked to lead a set would choose the music and the steps, and relay her request to the Master of Ceremonies. As mentioned in my post about the dances at the Netherfield Ball, the musicians would play contemporary and lively music requested by the lady. Most of the marriageable young girls (think of the exuberance of Lydia and Kitty Bennet) preferred their version of modern music to the tunes of their elders. This means that many of the tunes chosen for the ball scenes in the Jane Austen film adaptations are entirely wrong! The early nineteenth century teen would have balked at dancing to a staid Mr. Beveridge’s Maggot, no matter how much today’s viewers like the scenes in which this tune is featured.

1817 Accidents in Quadrille Dancing

List of sources and examples:

Read Full Post »