What can be more appropriate than to discuss body snatching on the very weekend of All Hallow’s Eve, when witches and goblins and ghosts wander throughout the night? This post will offer a variety of facts about grave robbers, resurrectionists, and sack-em-up gentlemen who haunted cemeteries, waiting for a fresh body to snatch.

Since the 15th century, British anatomists have been on the hunt for fresh cadavers to dissect and study. By the 18th century medical students were expected to gain practical knowledge of the human body through dissection as a pre-requisite for becoming licensed surgeons. It was the custom to study the corpses of criminals who had been executed for murder, but with the proliferation of medical schools, demand for anatomical specimens outpaced the supply. Medical students turned to stealing corpses for their own use, and thus, during this early period of body snatching, grave robbers belonged primarily to the class of ‘gentlemen’.

“By 1820 statutes defining crimes with capital punishments numbered over two hundred. In the words of barrister Charles Phillips, “We hanged for everything- for a shilling- for five shillings- for five pounds- for cattle- for coining- for forgery, even for witchcraft- for things that were and things that could not be”. An act of Parliament during 1752 further outraged the public by making hanging in chains or dissection of those condemned to death for murder mandatory. – Canadian Content

“The gruesome trade [of Resurrectionists] was driven by laws which only permitted the bodies of executed criminals to be used for medical science at the height of the Enlightenment. But with only about 50 executions being carried in London every year and a lack of refrigeration meaning that specimens rapidly putrefied, demand for about 500 bodies each year far outstripped supply.” – The Independent

The laws for grave robbing had not quite caught up with the times, for those who carried away an unclothed body could not be touched, but if they so much as took one sock or piece of clothing with it, they could be hung. The corpse was hastily stuffed in a sack, and hauled to the nearest medical school before the robbery was detected.

Medical students and their professors snatched bodies throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, but due to a lucrative business, an entirely new criminal element emerged: the resurrection men or gang of grave robbers. Many of these men made quite a tidy living. Resurrectionists were so efficient and became so indispensible to anatomists, that prominent physicians and surgeons would often exert their influence to keep them out of jail:

“Typically, a member of the gang, or his wife, would spend the day loitering in a likely graveyard waiting for a funeral…At night, two members of the gang would appear and, after carefully laying a sheet on the ground, would uncover the head portion of the grave, dumping the loose dirt on the sheet. The body would be pulled from the coffin head first with ropes, the shroud stuffed back in the grave, and the dirt carefully replaced.” – Body Snatching: A Grave Medical Problem, p 401

The business of selling bodies was such a good money maker that some people even kidnapped and murdered children in order to sell their bodies to the highest bidder. One such prolific grave robber was John Bishop, who was actually tried and convicted of murdering a 14 year old boy for the purposes of selling him to a surgeon. All together Bishop admitted to stealing between 500 and 1000 corpses and of murdering 3 people to sell their bodies, although that number could be higher. – Histatic blog

Look out posts in cemeteries were common, and relatives took turns watching the graves to protect their recently buried loved ones. “In the centre of the ancients have it all to themselves. Here we are in a bygone age. There is a thin iron standard with a lamp frame — a famous relic of the body-snatching days. They had no watch-house here, and so the relatives of the recently-interred lighted the lamp and sat by the graveside every night for the usual period.” – Mallusk Burying Ground

The families of the dead tried to purchase robber-proof coffins made with metal. There was a catch, however. Only the very rich owned the land in perpetuity in which they were buried. While their vaults could be secured and reinforced, ordinary people were buried in plots of land that were reused time and again. Thus, wrought iron and metal coffins designed to stave off grave robbers made the practice of recycling bodies in one plot impossible, and many cemeteries began to refuse such reinforced coffins.

“Opposition to the body-snatchers took many forms. Mourners often set spring guns and other booby traps over fresh graves to discourage the body-snatchers, and it was not uncommon for relatives to mount a night watch over a fresh grave for 2 or 3 weeks until the body had decomposed sufficiently to be useless for dissection.” – A Grave Medical Problem, p. 403

In Richmond, Virginia, 19th century Resurrectionists had only 10 days in which to procure a newly buried body. If the robbers waited longer, the body would be too putrid to be useful. The best months for grave robbing and dissection in Richmond were between October and March, when the weather was cool enough to slow down the rate of decomposition.

One assumes that the bodies were dead before they were delivered to anatomists. This was not always the case, as in this incident in 1816, when the subject delivered to Mr. Brooke’s Theatre of Anatomy was still very much warm and alive:

“October 21st Marlborough Street. It was stated yesterday that a most extraordinary affair happened at Mr Brooke’s The Theatre of Anatomy Blenheim Street. On Sunday evening a man, having been delivered there as a subject, a technical name for a dead man for dissection in a sack, who, when in the act of being rolled down the steps to the vaults, turned out to be alive, and was conveyed in a state of nudity to St James’s Watch house.

Curiosity had led many hundreds of persons to the watch house, and it was with difficulty the subject could be conveyed to this Office, where there was also a great assemblage. The Subject at length arrived. He stated his name to be Robert Morgan, by trade a smith. John Bottomley, a hackney Coachman, was charged also with having delivered Morgan tied up in the Sack. The Subject appeared in the sack in the same way in which he was taken, with this difference, that holes had been made to let his arms through.

The evidence of Mr Brookes afforded much merriment. He stated that on Sunday evenin,g soon after seven o clock, his servant informed him, through the medium of a pupil, that a coachman had called to inquire if he wanted a subject from Chapman, a notorious resurrection man. Mr B agreed to have i,t and in about five minutes afterwards a Coach was driven up to the door, and a man answering to the description of Bottomley brought Morgan in a sack as a dead body, laid him in the passage at the top of the kitchen stairs, and walked away without taking any further notice. On Harris witness’s servant taking hold of the subject’s feet, which protruded through the bottom of the sack, he felt them warm and that the subject was alive.

Here the prisoner Morgan, who seems to have enjoyed the narrative with others, burst out into a fit of laughter.

Mr Burrowes, the Magistrate – ” Is it usual, Mr Brookes, when you receive a subject, to have any conversation with the parties who deliver it?”

Mr Brookes – ” Sometimes, but dead bodies are frequently left, and I recompense the procurers at my leisure.”

Mr Brookes resumed his evidence, and stated that he put his foot upon the sack ,upon being called by his servant, and kicked it down two steps, when the subject called out: “I m alive,” and forcing half his naked body out of the sack threw the whole house into alarm. – Social England Under the Regency, Vol 2, John Ashton, 1816, p 114

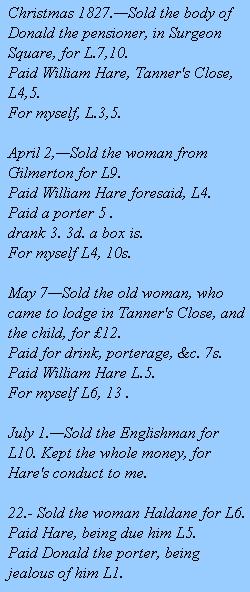

William Burke and William Hare, infamous body snatchers from Edinburgh, Scotland, delivered bodies that were remarkably fresh. It turns out that in their zeal to earn a quite comfortable living, they murdered at least 17 victims.

Over time, anatomists began to recognize the bodies the two men delivered but kept silent about their suspicions. Burke tempted fate one time too often. On Halloween night in 1827, he met Mrs. Docherty at a bar and persuaded her to drink with him at his lodgings. After much jollying and merriment, he killed the woman (his favorite method was suffocation, so as not to leave a mark).

But Burke was so drunk and addled that he was unable to dispose of her body in a timely manner. His landlady and neighbors discovered poor Mrs. Docherty’s body the following day, and Burke was made to stand trial. The public was incensed upon learning that Burke and Hare killed their subjects, and from then on the act of killing people to obtain biological specimens for anatomists was known as Burking.

Burke and Hare were arrested in 1828. Hare turned king’s evidence, and Burke was found guilty and hanged at the Lawnmarket, the Royal Mile, on the 28th January 1829. Burke’s body was publicly dissected at the Edinburgh Medical College and his skeleton, death mask, and items such as a leather wallet made from his tanned skin are now displayed at the Royal College of Surgeon’s museum. – Burke and Hare

The story is so fascinating, that it has been filmed and covered in the press repeatedly. Watch this preview of a film on Burke and Hare by John Landis that will make its debut in the UK first.

Over time, public outrage over body snatching and the abuses with the Royal College of Surgeons and the hospitals in relation to the resurrectionist trade became such that Parliament passed the Anatomy Act in 1832, which sanctioned the delivery of the corpses of any unclaimed dead to anatomy schools. During this period, hospitals were considered death houses, and all but the most desperately ill people avoided going to them. People also avoided dying in workhouses for fear of having their bodies claimed for dissection. While the practice of dissection was legitimized by this act, poor people were still fearful of having their bodies “snatched”, albeit legally.

More on the topic: