Book Review by Brenda S. Cox

“Loving Jane Austen, to me, is dependent on continuing to find something new to appreciate, mull over, research, or reconsider in her writings. What’s wild is that although her books don’t change, I do. . . . Reading, and loving, Austen’s fiction means something far different to me at fifty-seven than it did at seventeen.”—Wild for Austen, 262.

A few days ago we reviewed Living with Jane Austen by Janet Todd. Today we get a personal perspective from another Austen expert, Devoney Looser, giving her view of Jane Austen as ‘wild,’ in Wild for Austen.

Wild for Austen: A Rebellious, Subversive, and Untamed Jane, by Devoney Looser

Devoney (DEV-uh-nee) Looser takes pride in being rather ‘wild’ herself. She dedicates this book to people in “the international roller derby community,” saying: “You got me rolling, knocked me down, and lifted me up, not only as Stone Cold Jane Austen [Looser’s roller derby name] but as a stronger and more joyful teacher-scholar.”

Devoney’s goal is to demolish the “myth of Jane Austen as a quiet, bland spinster.” She finds ‘wildness’ in Austen’s novels, in the lives of Austen’s connections, and in Austen’s ‘afterlives.’

Looser says ‘wild’ is ‘a linchpin word in Austen’s fiction.’ In the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), we find examples from Jane Austen for the earliest uses of ‘wild’ to mean ‘passionately or excitedly desirous to do something’ (Mrs. Palmer is ‘wild to buy all’ in S&S; Elizabeth is ‘wild to be at home’ in P&P; the Musgrove girls are ‘wild for dancing’ in Persuasion). ‘Wild’ can also mean ‘elated, enthusiastic, raving’ (“The men are all wild after Miss Elliot.”). The OED also defines ‘wild’ as ‘artless, free, unconventional, fanciful, or romantic in style,’ which Looser says characterizes Austen’s novels.

Looser also argues against the myth of “Austen’s fiction having been largely forgotten until 1870. It wasn’t.” Austen’s novels were apparently widely read and familiar throughout the 1800s. Looser gives examples, from the years following Jane’s death, of the novels mentioned in magazines, poems, and a court case. Here’s an example I like: “Mansfield Park was said to be the secretly chosen favorite (on private slips of paper) of seven distinguished literary gentlemen in 1862.” Looser has also found clear imitations of Austen in other stories published in the 1800s.

Chapters in Wild for Austen

Part I: Wild Writings

- Introduction: Austen Gone Wild

- Fierce, Wild, and Ruthless: Austen’s Juvenilia

- The Controversial Case of Sophia Sentiment (a letter in her brothers’ periodical The Loiterer, possibly Jane’s first published work)

- Running Wild: The Winning Immorality of Lady Susan

- Wildest: Sense and Sensibility (1811)

- Almost Wild: Pride and Prejudice (1813)

- Bewildering Mansfield Park (1814)

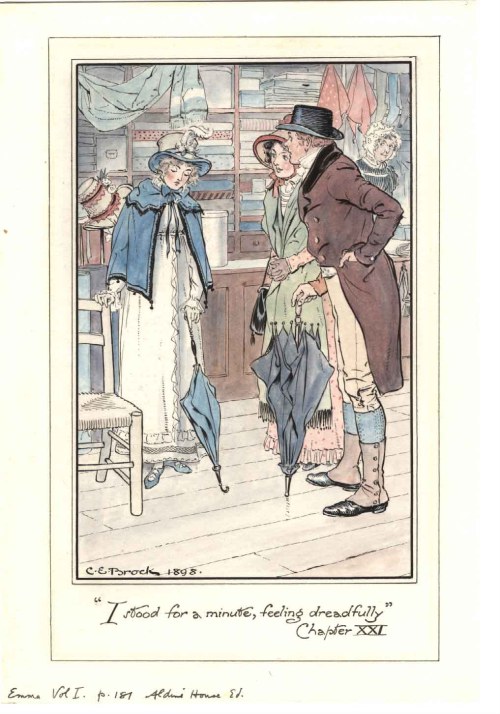

- Wild Speculation: Emma (1816)

- Wild to Know: Northanger Abbey (1818)

- The Young People Were All Wild: Persuasion (1818)

- Wild-Goose Chase: Unfinished Sanditon (111)

- Oh, Subjects Rebellious: The Watsons and Last Words

Part II: Fierce Family Ties (explores unexpected people and events among Austen’s family and acquaintances)

- Jane, the Wild Beast, and the Progressive Burdetts

- Cousin Eliza’s Statesman, Singer, and Spy (a lurid murder of Austen’s acquaintances)

- The Leighs as Learned Literary Ladies (authors among Austen’s relatives)

- The Sensational Shoplifting Trial of Aunt Jane Leigh Perrot

- Three Austen Brothers and the Abolition of Slavery (new evidence about Frank, Charles, and Henry)

- The Austen Family Legacy, Suffrage, and Anti-Suffrage (Austen descendants for and against the vote for women)

Part III: Shambolic Afterlives (how people have seen and adapted Austen since her death. ‘Shambolic’ means ‘chaotic.’)

- Seeing Jane Austen’s Ghost

- Sense and Sensibility Goes to Court (Quotes from S&S were used as evidence in an 1825 breach of promise suit, to support the idea that a woman would not fall in love with a much older man; counsel had obviously not read the whole book! Austen’s novels have also been cited in much more recent court cases.)

- Jane’s Imaginary Lover in Switzerland (Fake news in 1886 went viral.)

- Almost Pride and Prejudice: The Wild Films That Never Were

- Wild and Wanton: The Rise of Austen Erotica

- Loving (and Hating) Jane Austen

- Coda: Austen After 250

Personally, I found the first two sections the most interesting. I’m still not convinced that Austen’s novels are what I would call ‘wild,’ though the Juvenilia and Lady Susan certainly are! But Looser brought out many intriguing insights about each novel, looking at the use of ‘wild’ in the books.

For example, she shows Sense and Sensibility defying expectations of romance novels: “the doublings and triplings, twists and turns, and backstories and backstabbings keep readers constantly on their toes” (46). Marianne is the “wildest,” speaking to Willoughby in “the wildest anxiety.” But the point of the story, recognized by early readers, is that both men and women should have a balance of both sense and sensibility; they need “both finely tuned minds and warm, rebellious feelings.” The best books should also “embody the best of both qualities” (57).

Mansfield Park has the least ‘wild’ heroine of the six novels. However, in my own humble opinion, it has the largest cast of other ‘wild’ characters—Henry Crawford, who commits arguably the worst action of the villains by eloping with a married woman, breaking up Maria’s marriage with no intention of marrying her; Mary Crawford, who makes a dirty joke and considers adultery ‘folly’; and Maria, who marries a man she hates and leaves him for a man she has already seen to be trifling and insincere. Julia, of course, elopes, which was also considered ‘wild.’ Tom Bertram not only convinces his household to put on a morally questionable play, but is so wild he drinks himself almost to death. Looser says Mansfield Park may have been “a jarring reading experience” for 1814 readers. She considers the wildest thing about it to be “its prompting of lively, difficult arguments and rousing debates” (76).

Wild for Austen, by Devoney Looser, may help you see Austen, her writings, and her connections in a new light. Or give you fodder for lively arguments. Enjoy Austen’s ‘wildness’! (UK link)

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.