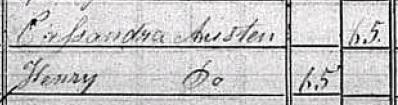

Inquiring Reader, This post is the second part of solving the mystery of Cassandra Austen’s age in the 1841 census, which reader Craig Piercey brought to my attention. A number of people became involved in the mystery of Cassandra’s age, which was 68 at the time the census was taken, but was listed as 65. To review the situation, click on this link and read the emails sent to explain the anomaly.

The first letter came from Laurel Ann of Austenprose, who had left a comment on the first post.

Vic, I have come across many discrepancies on census enumerations. The process is part of the problem. Families were asked to fill out their own sheets and then they gave them to the enumerator who transcribed them onto the sheets of record. The original family sheets do not survive. There is always the possibility of illegible handwriting, transcription error, the family did not understand the directions or people lied about their age! It is not considered a primary source document by the government or family historians. Cassandra’s christening record would serve as a legal record of her birth. Since her father filled this out, we can be pretty certain that it is correct. It is also confirmed in family letters. By her death in 1845 it was required to report deaths to the new Registrar and would have included a doctor’s verification. That is the best explanation I can offer. The government was primarily interested in numbers. They used the data for general ranges like the number of children under 10 or men of military age etc. The fact that exact ages are listed from 1851 onward is a bonus to family historians now, but not so much for the government then. Census records are not an exact science. I am glad you had so much interest in this puzzle. The discrepancy does appear odd to one who has not done family research. I hope this is helpful. LA

Laurel Ann was not the first person to point out that the Census taker would use a general number that could be divided by five. Before I received her answer, I had written to Ray Moseley, Fundraising Administrator of Chawton House. He replied promptly:

Dear Vic,

Sarah Parry our education officer at Chawton House has replied as below. I do hope that this helps. If we can of any further help please don’t hesitate to contact me.

Ray

Hi Ray

I think that the following might be an explanation.

This is the web page for the 1841 census on the National Archive website: http://search.ancestry.co.uk/iexec/Default.aspx?htx=List&dbid=8978&ti=5538&r=5538&o_xid=24149&o_lid=24149&offerid=0%3a21318%3a0 It makes the point about how ages were recorded on this census and notes if over 15, the ages “were usually rounded down to the nearest 5 years”.

I also had a look at Deirdre le Faye’s A Chronology of Jane Austen and her Family (Cambridge University Press 2006). The entry referring to the 1841 census reads:

“June 6, Sunday

National census this year shows CEA [Cassandra Elizabeth Austen] living at Chawton Cottage, with three maids – Mary Butter, Emily Kemp, Jane Tidman – and one manservant, William Sharp. HTA [Henry Thomas Austen] and Eleanor Jackson are also there on census night.”Cassandra was born on 9 January 1773 and would have been 68 on the night of the census so it would have been correct, by the format of the 1841 census, to show her age as 65.

Henry would have celebrated his 70th birthday in 1841. He was born on 8 June 1771. The 1841 census was taken on 6 June – just two days before his 70th birthday. So the figures are correct as Henry would have been 69 on the night of the census so again, by the format of how to record ages in the 1841, census it would therefore have been quite correct to show his age as 65. Henry’s surname isn’t shown on the census because the mark below the “Austen” of Cassandra’s name and alongside Henry’s Christian name is the equivalent of ditto marks.

Hope this helps.

Best

Sarah

Sarah’s explanation dovetails in with other speculations, but because she works for Chawton House as an education officer, I will take hers as the last word on the subject.

Tony Grant, London Calling, wrote Louise West at the Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton about the same time that I wrote Chawton House, and her reply, while supportive, did not include additional information.

Hi Vic,

I just received this today from Louise West at Chawton Cottage. Remember our exciting foray into working out Cassandra’s age? … Here you are. – TonyDear Tony

Many thanks for sharing with me this interesting correspondence. I really admire all the effort that has gone into trying to solve the mystery and wish I could offer anything more illuminating but I’m afraid I’m as much in the dark as you are. If you uncover anything definite I would be very interested to hear.

Best wishes

Louise West

Collections and Education Manager

Jane Austen’s House Museum

Chawton

Alton

So, gentle reader. This is the end of our research into this topic. I hope others have found this journey into uncovering a mystery as interesting as I have. Thank you for stopping by, and thanks to all who have answered our emails and helped, especially Laurel Ann, whose initial comments and follow-up email unlocked the mystery first.