by Brenda S. Cox

“I dread the idea of going to Bookham as much as you can do”—Jan. 9, 1799

“My scheme is to take Bookham in my way home for a few days . . . I have a most kind repetition of Mrs. Cooke’s two or three dozen invitations, with the offer of meeting me anywhere” –Nov. 3, 1813

We’ve been looking at some of Jane’s mother’s Leigh family. The Austens also corresponded regularly with the Cooke family in Great Bookham, who are often mentioned in Jane’s letters. Mrs. Cooke was Jane’s mother’s cousin. Her name was the same as Jane’s mother’s: Cassandra Leigh. She was the daughter of Jane’s uncle Theophilus Leigh, master of Balliol College at Oxford.

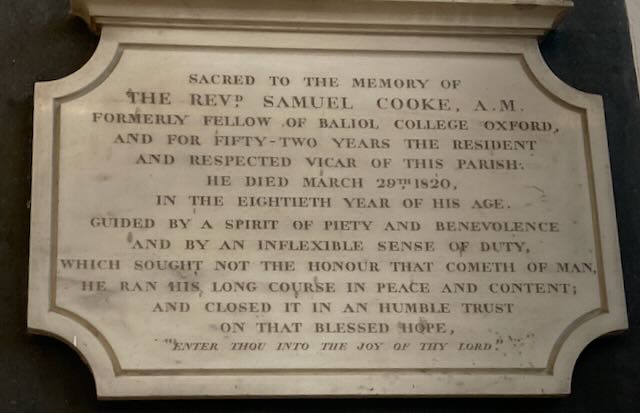

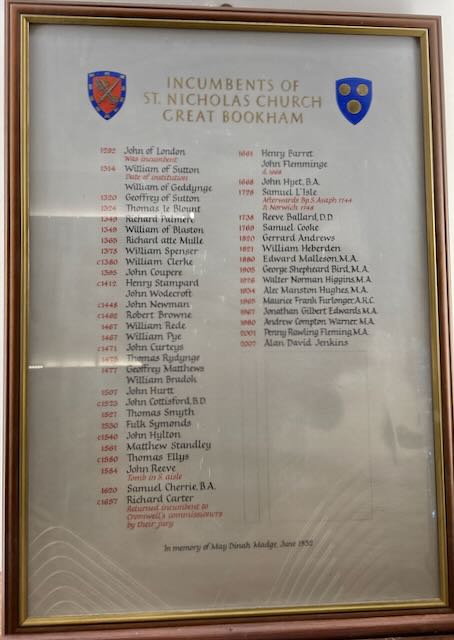

This cousin’s husband, Rev. Samuel Cooke, was Jane’s godfather. He was the vicar of St. Nicolas’, Great Bookham. He was also rector of Cottisford, Oxon, about 80 miles away, but he and his family lived in Great Bookham.

Godparents play an important role in Anglican families.They promise to pray for the child’s salvation, faith, and obedience, and, at the child’s baptism, they renounce the devil on the child’s behalf. A girl has one godfather and two godmothers.

Jane Austen visited the Cookes in Great Bookham, which is between Chawton and London, a number of times. We don’t know why she did not want to go there in 1799, but she visited from May 14 to June 2.

Great Bookham in Austen’s Novels

Jane made good use of her visit. In 1801, she started writing The Watsons. Its setting in “Stanton” was apparently based on West Humble (now Westhumble), a town near Great Bookham. It is three miles from Dorking, which Austen calls “the town of D. in Surrey.” Betchworth Castle is nearby, so it may be the basis for Osborne Castle in the novel.

After probably visiting several more times, in the summer of 1814, Austen decided to visit the Cookes again. On June 14, she wrote,

“The only Letter to day is from Mrs. Cooke to me. They . . . want me to come to them according to my promise.—And after considering everything, I have resolved on going. . . . In addition to their standing claims on me, they admire Mansfield Park exceedingly. Mr. Cooke says ‘it is the most sensible Novel he ever read’—and the manner in which I treat the Clergy, delights them very much.—Altogether I must go–& I want you [Cassandra] to join me there . . .”

One commentator (Chapmen) says the Cookes may have had Evangelical leanings and appreciated Mansfield Park’s protext against lax views of the duties of the clergy. Evangelical or not, Edmund Bertram of Mansfield Park does present a very high view of the clergy. He says, for example:

“I cannot call that situation [of clergyman] nothing which has the charge of all that is of the first importance to mankind, individually or collectively considered, temporally and eternally, which has the guardianship of religion and morals, and consequently of the manners which result from their influence. No one here can call the office nothing. . . . it will, I believe, be everywhere found, that as the clergy are, or are not what they ought to be, so are the rest of the nation.”

When Jane Austen visited in 1814, she was in the midst of writing Emma. She later told her nephew that Leatherhead, next to Great Bookham, was the model for Highbury. Box Hill, where Emma and her friends picnic, is nearby, and Great Bookham had an Old Crown Inn similar to the one in Highbury. (It was, however, demolished in 1930). There was also a Randalls Park, and other features similar to Highbury.

Box Hill

Box Hill is still a beautiful spot for picnics, hiking, walking, and cycling. The current rector of Great Bookham, Alan Jenkins, kindly took us to visit there. It includes a cycling trail. In the 2012 Olympics, cyclists made nine laps on this trail as part of their route.

The Parsonage

The Cookes’ parsonage, where Jane Austen stayed, was a large one. (A maid working there was named Elizabeth Bennet, by the way.) They had at least six children, but only three survived to adulthood. Their daughter Mary, who apparently did not marry, was a good friend of Jane’s, mentioned in her letters. Their son Theophilus Leigh Cooke (1778-1846) became a clergyman, a fellow of Magdalen College at Oxford, and holder of three church livings. His brother George Leigh Cooke (1779-1853) combined religion and science. He was a fellow of Corpus Christi College and earned a bachelor of divinity (a graduate degree). He also became a professor of Natural Philosophy (science) at Oxford, a keeper of the archives, and published an edition of Newton’s Principia Mathematica.

Until 1869, Great Bookham had vicars, not rectors. The patron of the parish (a person who changed over the years), took part of the tithes and the rest went to the vicar, along with income from the glebe farmland belonging to the living. It is speculated that some of the excommunications in the Vestry Books were for non-payment of tithes (from 1800: Great Bookham at the Time of Jane Austen).

The parsonage was removed in 1961. For early pictures, see here. The parish now has a rector; the term no longer refers to tithes. His rectory is a modern building.

St. Nicolas’ Church, Great Bookham, History

Jane Austen must have worshiped in this church, where her godfather was the vicar, a number of times on her visits to Great Bookham.

When Austen visited, the church was full of box pews with walls around them. Some were three feet high, some were four feet high. The box pews were replaced by regular pews in 1885.

Other Literary Connections at Great Bookham

Great Bookham has a number of literary connections, some of which Jane Austen would have known about.

Fanny Burney wrote of the Cookes, “the father is worthy, the mother is good, so deserving, so liberal and so infinitely kind, that the world certainly does not abound with people to compare them with. The eldest son is a remarkably pleasing young man. The young seems sulky, as the sister is haughty.” She also wrote of Rev. Cooke, “Our vicar is a very worthy man and goodish—though by no means a marvellously rapid preacher.”

She also wrote to her father, Dr. Burney, “Mr. Cooke tells me he longs for nothing so much as a conversation with you on the subject of Parish Psalm singing—he complains that the Methodists run away with the regular congregation from their superiority in vocal devotion.” The Methodists, led by John and Charles Wesley, had been leading a revival in the church. They attracted people with lively hymns. Country churches were mostly singing psalms, often quite poorly, at this time, though hymns were beginning to be introduced into some churches.

Playwright and politician Richard Sheridan (1751-1816), who wrote The Rivals and School for Scandal, owned several manors in the area around Great Bookham.

Later, teenaged C. S. Lewis lived in Great Bookham from 1914-1917, being educated by a private tutor, William T. Kirkpatrick.

St. Nicolas’ Church, Great Bookham, Today

St. Nicolas’ is a very active church, larger than the others we have “visited” so far. I was told the parish includes eleven to twelve thousand people. The electoral role of St. Nicolas’ lists about 250 members, and around 140 attend on Sundays. Three other ministers and five staff members assist the rector in serving the church. The church holds services every Sunday, Communion on Thursdays and Sundays, and several weekly prayer meetings. Members also meet in housegroups.

The area also includes Baptist, Catholic, and United Reformed churches, and St. Nicolas’ cooperates with them on projects like Alpha Courses, designed to address people’s questions about Christian faith.

A few years ago, the church removed the Victorian pews and substituted chairs. This gives them the flexibility to hold various kinds of services and to host community events.

Religious education and daily worship are required to be offered in British government schools (student participation is optional). The rector, Alan Jenkins, provides some of this in local schools, briefly sharing a Bible story, prayer, and sometimes a song. School groups also come into the church for harvest or Easter services, with programs organized by the teachers.

I hope you are enjoying learning about Jane Austen’s churches along with me. There is so much history at these old churches, as well as continuing community life and worship today.

All photos copyright Brenda S. Cox, 2024.

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.

Sources

1800: Great Bookham at the Time of Jane Austen, Fanny Burney, and R. B. Sheridan, published by the Parochial Council of St. Nicolas Great Bookham (booklet available at the church, funded by JASNA)

“The Original of Highbury,” Jane Austen Society Collected Reports II:60,

Church of St. Nicolas, official list entry

St. Nicolas, Great Bookham website and The History of the Building

Special thanks to Tony Grant for telling me that Box Hill was near Great Bookham, and to Rev. Alan Jenkins for taking us up to Box Hill!

Further Exploration

Jane Austen and Great Bookham, by Tony Grant

Box Hill in Jane Austen’s Emma, by Tony Grant (includes the geology, history, and literary connections of Box Hill)

Jane Austen’s Surrey, by Tony Grant (includes views Emma might have seen on her picnic)

Emma Woodhouse’s Surrey, by Tony Grant (includes views Emma might have seen on her picnic)

Other Churches Connected to Jane Austen

Hamstall Ridware and Austen’s cousin Edward Cooper