by Brenda S. Cox

“Madam” Anne Lefroy

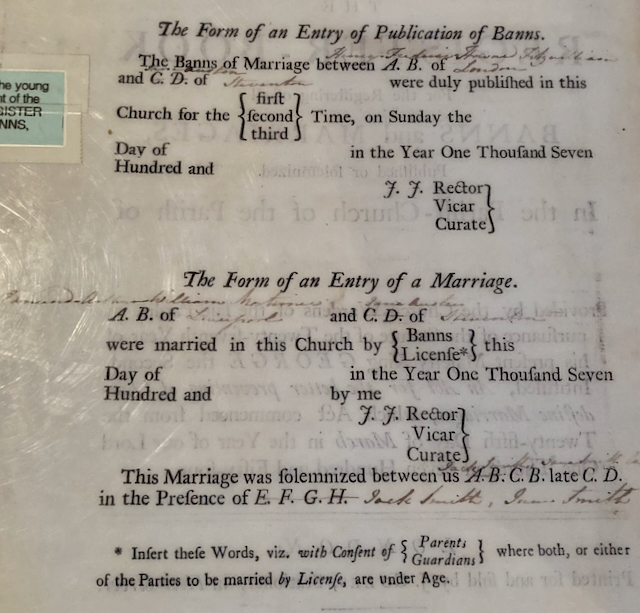

Anne Lefroy, a dear friend of young Jane Austen, lived about two and a half miles north of Steventon, in the village of Ashe. Wealthy Benjamin Langlois was patron of the parish church, and he gave the living of Ashe to his nephew, Reverend Isaac Peter George Lefroy (called George) in 1783, when Jane was eight years old. At that time the church was called St. Andrew’s, and Ashe was spelled Ash.

Rev. Lefroy’s wife was Anne Lefroy, cultured, educated, and hospitable. She wrote poetry, and had two witty poems published before her marriage. Because of her sophistication and hospitality, in the neighbourhood she was “known affectionately and respectfully” as Madam Lefroy. Mrs. Lefroy was 25 years older than Jane. So how did they become friends? According to information sheets at the church,

“Anne Lefroy and Jane Austen, despite their age difference, formed a close friendship that started when the Lefroys invited the 11-year-old Jane to play with their 7-year-old daughter. Due to a mutual love of literature, Anne and Jane are believed to have had long literary discussions. Jane was allowed access to the extensive library of the Ashe rectory. Jane may also have shared her writing with Anne who, some have suggested, acted as a surrogate parent. This must have acted as an important source of support for Jane in her early years of writing.”

This is speculative. But Mrs. Lefroy is often mentioned in Jane Austen’s letters. Jane frequently visited the Lefroys’ parsonage and attended dances and parties there and at the local squire’s house, Ashe Park.

Tom Lefroy

Famously, Jane danced and flirted with George Lefroy’s nephew from Ireland, Tom Lefroy, when he came for a visit in 1796. She wrote to Cassandra, “Imagine to yourself everything most profligate and shocking in the way of dancing and sitting down together” (Jan. 9, 1796). A week later, on January 15, she wrote, “At length the Day is come on which I am to flirt my last with Tom Lefroy. . . . My tears flow as I write, at the melancholy idea.” She immediately starts another topic and we don’t know if she was joking or serious. She may have hoped to marry Tom, but a proposal never came.

It’s been speculated that Rev. and Mrs. Lefroy sent him away, since he needed to marry someone with more money than the Austens had. Or Tom himself may have decided to leave, and the Lefroys were disappointed in him for flirting and not following through. Jane said Tom was “laughed at” at Ashe because of her, so it might have all been teasing, not serious. In any case, Jane does not seem to have held the outcome against Tom or against Mrs. Lefroy. After all, as she wrote in Pride and Prejudice, “Handsome young men must have something to live on as well as the plain.”

(Tom Lefroy, by the way, pursued a legal career and became a chief justice of Ireland. His son Jeffrey became a churchman, dean of Dromore Cathedral in Ireland, and Tom’s grandson George Alfred Lefroy became an Anglican clergyman and a missionary to India, then Bishop of Lahore and Calcutta. He is remembered for opposing western racism toward Indians.)

Mrs. Lefroy apparently tried to set Jane up later with another friend, the Reverend Samual Blackall, who Jane later called “a piece of . . . noisy perfection . . . which I always recollect with regard.” But nothing came of that, either.

Jane Austen’s Poem

The strongest testimony of Jane’s attachment to Mrs. Lefroy is a poem Jane wrote to her in 1808. Four years earlier, Mrs. Lefroy had been thrown from her horse and died on Jane’s birthday, December 16.

In the poem, Jane calls Mrs. Lefroy “beloved friend,” and says the reminder of her death is a “bitter pang of torturing Memory.” She describes her:

Angelic Woman! past my power to praise

In Language meet, thy Talents, Temper, Mind.

Thy solid Worth, thy captivating Grace! –

Thou friend and ornament of Humankind! –

She says Mrs. Lefroy was unequalled, angelic, “with all her smiles benign, Her looks of eager Love, her accents sweet.” She spoke with “sense, . . . Genius, Taste, & Tenderness of soul.”

Jane also praises Mrs. Lefroy’s religious principles:

“She speaks; ’tis Eloquence–that grace of Tongue

So rare, so lovely! – Never misapplied

By her to palliate Vice, or deck a Wrong,

She speaks and reasons but on Virtue’s side.Hers is the Energy of Soul sincere.

Her Christian Spirit, ignorant to feign,

Seeks but to comfort, heal, enlighten, chear,

Confer a pleasure, or prevent a pain. –Can ought enhance such Goodness? – Yes, to me,

Her partial favour from my earliest years

Consummates all. – Ah! Give me yet to see

Her smile of Love. – the Vision disappears.

And Jane says she hopes to meet her again in heaven.

Mrs. Lefroy as a Clergyman’s Wife

Interestingly, Jane’s tribute is similar to Mrs. Lefroy’s obituary. One section says:

“Her religion predominated over all her excellencies, and influenced and exalted every expression and action of her life. How amiable and angelic she was in the domestic duties of daughter, wife, mother, and sister, . . . She has left a chasm in society. . . . Above all, the poor will receive this afflicting dispensation of Providence with the keenest sorrow and lamentation: she fed, she cloathed, she instructed them, with daily and never-ceasing attention; in grief she soothed them by her conversation and her kind looks; and in sickness, she comforted them by medicines and advice. . . .”

Mrs. Lefroy was very attached to her children, as we see in her letters to her son Christopher Edward. They have been published by the Jane Austen Society. Mrs. Lefroy ran a school from her home. She said teaching other children helped her to not miss her own children so much when they were away at school. She taught poor children to read and write and gave them practical skills to help them support themselves.

Like most clergy wives, she was also involved in medicating her parish as needed, but she took that a huge step further. Smallpox was a great killer in those days. When Mrs. Lefroy learned about the brand-new system of vaccination, she investigated and determined it was beneficial. Then she learned to do it herself, and vaccinated her own family and over 800 poor people, giving them protection from smallpox. The obituary concludes, “Thus she seemed like a ministering Angel, going about to dispense unmingled good in the world.”

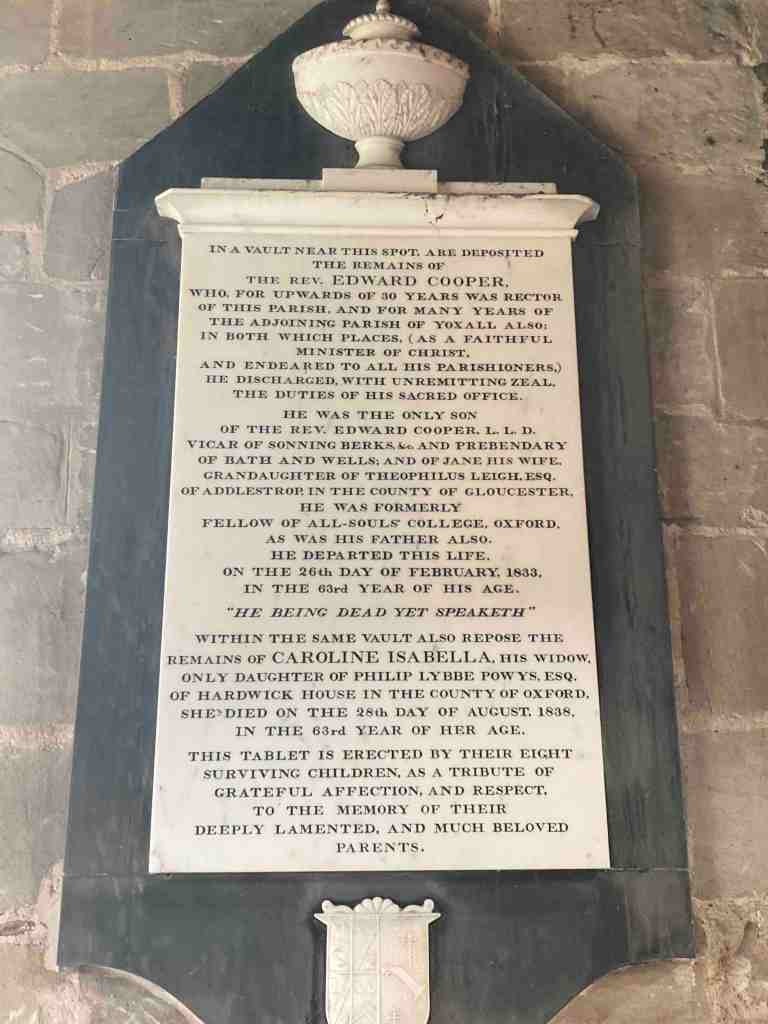

Ashe Church Memorials to the Lefroy Family

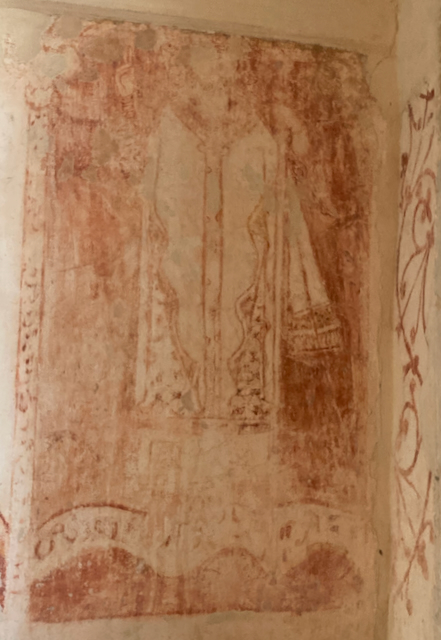

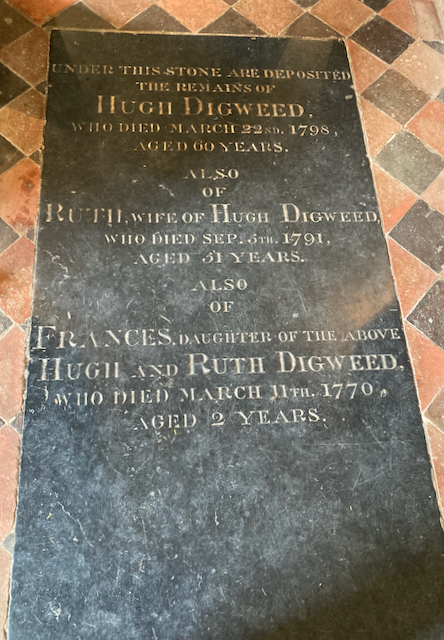

While most of the Ashe church is Victorian, a number of memorials remain from Austen’s time. Her Lefroy friends are all buried there.

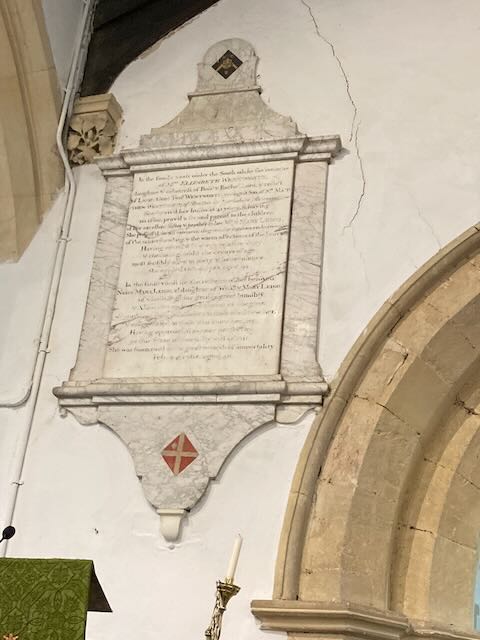

The memorial to George and Anne Lefroy is very hard to read now, but a page in the church gives the text. The facts of their deaths are followed by:

“Reader: The characters here recorded need no laboured panegyric; prompted by the elevate dictates of Christianity, of whose glorious truths they are most firm believers, they were alike exemplary in the performance of every duty, and amicable in every relationship of life; to their fervent piety their strict integrity, their active and comprehensive charity, and in short to the lovely and useful tenor of their whole lives and conversations those amongst us who they lived, and especially the inhabitants of this parish, will bear ample and ready testimony, after a union of 26 years, having been separated by death scarcely more than 12 months, their earthy remains are together deposited in peace near this marble. Together be raised. We humbly trust in glory when the grave shall give up her dead, and death itself be swallowed up in Victory

Rev. 14 v. 13

Blessed are the dead, which die in the Lord, even so saith the spirit for they rest from their labours.”

William Thomas Lefroy was only three years old when he “Died Alas!” as the plaque says. His brother Anthony Brydges Lefroy was fifteen when he died of an enlarged heart; they speculated it was the result of him falling from a horse two years earlier and not being bled by the doctor. Anne may have written the poem commemorating her son: “Such patient sweetness, such untainted youth, such early piety, and spotless truth; were lent a few short years to point the way; to heaven’s blessed courts, realms of endless day.” The plaque also commemorates their brother Christopher Edward, recipient of Anne’s letters, who lived to the ripe age of 71.

The memorial to their son John Henry, the next rector of Ashe, focuses a great deal on his parents, George and Anne, who apparently taught him well: [brackets added]

“Heir to the same glorious hopes, he pursued with undeviating fidelity the example of his parents, whose characters are recorded on the adjacent marble. Distrustful alike of clamourous profession [religious ‘enthusiasm’] and philosophical liberality [Deism], he daily sought, with anxious singleness of eye [focus], amidst the tumult of religious opinions, the narrow practical way of Christianity. Imbued from his infancy with the deepest reverence for the benignant [kind, good] character and divine authority of Christ, the spirit of Christianity pervaded his whole walk and conversation; in all the relations of son, brother, husband, father, as a minister, a magistrate, a man, his constant affection, his earnest benevolence, his scrupulous integrity were equally conspicuous; utterly rejecting at the same time, all presumptuous dependence on his own merits, his humble and only confidence in death, as through life, was in the one full perfect, and sufficient sacrifice of his saviour upon the cross, for the sins of the whole world. Having, thus, maintained through life, his parents character, and died in his parents faith, here, at the early age of forty one, he reposes in his parents grave, having left a widow and eleven children to cultivate the memory of his excellence, exert themselves to follow his footsteps, and deplore their irreparable loss.”

Wow! I don’t know who wrote that, but this was an impressive family.

John Henry’s brother Benjamin Lefroy married Jane’s beloved niece Anna Austen (daughter of Jane’s clergyman brother James). Benjamin followed John Henry as the next rector, for only four more years until he died in 1829, age 38. A poem recalling Christ’s resurrection commemorates Ben Lefroy’s life, and the life of his wife Anna, who died near Reading in 1872, age 79.

“When by a good man’s grave I muse alone,

Methinks an angel sits upon the stone;

Like those of old on that thrice-hallowed night.

Who sate and watched in raiment heavenly bright,

And, with a voice inspiring joy, not fear,

Says, pointing upward, that he is not here.”

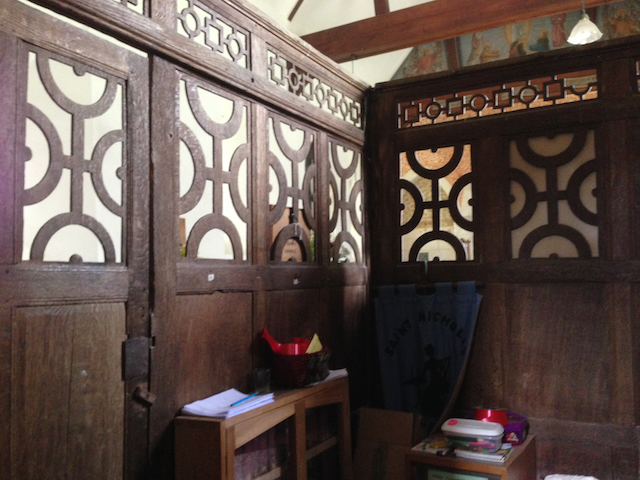

Holy Trinity and St. Andrew’s Church, Ashe, Today

There has been a church in Ashe since Norman times. In 1851, during the only Religious Census taken in England, the church had a seating capacity of 140. Their attendance at the morning service that Sunday was 98, and at the afternoon service, 120.

However, like many English rural parishes today, the area is now mostly farmland with only about 100 residents in the parish. About 10-15 people attend the church’s Sunday services twice a month. Of course they can attend other churches nearby on the alternate Sundays. Ashe is in a combined benefice with Steventon, Deane, and North Waltham, and they sometimes combine events with the adjoining benefice of Overton. Special services bring in more people; Ashe may fill the church with 140 worshipers at Christmas. They occasionally host weddings; special services, including one for blessing pets; and other events.

Fiona Price, our guide to the church, said she and her young grandson love the peace and tranquility of the place. Holy Trinity and St. Andrew’s Church at Ashe is an interesting church to visit, near Steventon. It would have been about an hour’s walk away for Jane Austen.

All images in this post ©Brenda S. Cox, 2024.

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.

The obituary is quoted from a “Provincial Newspaper” in a footnote to S.E. Bridges, “Lines to the Memory of Mrs. Lefroy,” in The Poetical Register, 1805 (London: Rivington, 1807): 67–68.

Further Resources

The Letters of Mrs. Lefroy, edited by Helen Lefroy and Gavin Turner, published by the Jane Austen Society (U.K.) This is hard to get hold of in the US, though I found it through Inter-Library Loan. I thought it gave the best insights into Mrs. Lefroy, her character, thoughts, and life.

Jane Austen’s Inspiration: Beloved Friend Anne Lefroy, by Judith Stove, explores Anne Lefroy’s life, writings, and family connections.

Posts on Other Austen Family Churches

Adlestrop and the Leigh Family