Dr Gillian Dooley, Photo @IASH-The University of Edinburgh

Inquiring Readers, In early March, I reviewed Gillian Dooley’s book, She played and sang: Jane Austen and music, published by Manchester University Press. While I knew some information about the Austen family’s collection of music books from the Internet Archive and several JASNA articles, none were as comprehensive as Dr. Dooley’s book. Her book now sits proudly on my library shelves in the Jane Austen section, where It will be used often as reference material. I still had a few questions, which Dr. Dooley was kind enough to answer.

Q & A With Dr Gillian Dooley:

Question #1:

First, I want to thank you for writing this highly informative book. Almost all of the information contained in it is new to me. It’s obvious in Austen’s letters and novels that she loved music. I’m not a musician and sing off key, but I do love listening to classical music, especially from the late 18th and early 19th centuries– Haydn, Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven– and attending music concerts. I’ve read that the Austen family, like so many of their peers, read books out loud to each other when families gathered in the evening. They also played music and sang at home, with Austen playing the piano for her younger nieces and nephews as they danced. In her day, what were the connections, if any, between the music Austen collected and the stories in her novels?

Dooley:

Thanks for your interest in my book! I do discuss some possible links between her music collection and her writings, specifically in the juvenilia – where she often parodies the sentimental love songs of the time – and in Sense and Sensibility, where the plot has some structural similarities with a ballad named ‘Colin and Lucy’, of which she owned a copy. I don’t think that there are many direct or obvious connections, though. She rarely refers to an identifiable piece of music – ‘Robin Adair’ in Emma is the only explicit allusion and there are interesting emblematic resonances between that song and the plot. There are some other allusions to song texts in the novels that her contemporary readers might have noticed, but most of those songs are not in her music collection. I think they would have been common knowledge at the time, but we don’t necessarily recognize them now.

On the other hand, it would be possible to take almost any love song and find parallels in her novels, mainly because the narrative of most love stories includes roughly the same series of events: a meeting, getting acquainted, facing difficulties, and finally the happy ending. I guess what I’m saying is that what’s enduring and engaging about Austen’s novels is not their plots, but her use of language, her narrative voice, and her depiction of character. And I do think these aspects might be influenced by the fact that she was a musician. The rhythm of her language can be very musical, and in the songs she sang she would often have been acting the part of a character, or, in a way, embodying a character who might be quite different to herself.

Question #2:

Can you describe some of the pieces she copied that were her favorites? I’m struck at how few of the composers in Appendix 2 are familiar to me.

Dooley:

Appendix 2 of my book lists the pieces of music that Austen copied herself by hand. She also owned some printed scores that she might have bought or been given. Her music collection includes both piano music and songs. I spend some time in my book surveying the handwritten pieces because it seems to make sense that, having invested the time in making copies, they might the ones she liked most. But that’s only a guess and isn’t supported by her niece Caroline’s memories of hearing her sing in her last years ‘when she had nearly left off singing’: only one of the four songs she mentions is among the manuscripts.

These four songs are all in their way love songs. Two are Scottish songs, ‘Their Groves of Sweet Myrtle’ – which has words by Robert Burns – and ‘The Yellow-Haired Laddie’. Another song, in French, tells a sad story about swallows being separated and dying of love. And the fourth is from the English theatre – quite a sardonic song in its way, about a wife whose husband is leaving her. So though they share a sense of drama, they are all different in mood and character, and the singer has to interpret the songs through the character.

And as you say, not many of the composers are well known today. I have discovered several new favourite composers in the course of my research, including Stephen Storace, Giovanni Paisiello, François Devienne, and James Hook.

Question #3

I attend performances monthly given by our local chamber orchestra. The next performance will include Mozart’s Violin Concerto No 1 in B-Flat Major K. 207 (1773), written before Austen’s birth. It is divided into three movements– Allegro moderato, Adagio, and Presto. I understand that these three tempos indicate mood and expression. I’m struck that Austen’s novels are written in three parts. How do the divisions in music tempo relate to the pacing of her stories, or am I off base?

Dooley:

That’s an interesting thought! Form is important in any work of art, and especially in that era, most artists worked within various standard forms. For example, in music there is the da capo aria, and sonata form (made up of exposition – development – recapitulation), or theme and variations, or rondo – and, as you say, on a more macro level the 3-movement concerto or sonata. In poetry there were various standard metres and verse forms, e.g. the sonnet. Novels were usually in three volumes.

The Romantic movement pushed against some of these forms but they were remarkably persistent for a long time. Mozart and Haydn wrote amazing and idiosyncratic music, but it stayed mostly within these constraints. And Austen worked mainly within the form of the comic novel. There’s a very interesting book by Robert K. Wallace, Jane Austen and Mozart: Classical Equilibrium in Fiction and Music (Georgia UP, 1983), that compares Austen’s novels and Mozart’s concertos in detail.

I think there is an enduring rhetorical significance in the number three. And if you think of the way a novel like Pride and Prejudice divides into three parts, an argument could probably be made that the moods and tempi of the classical musical forms map approximately onto the structure of the novel. But only approximately.

Thank you so much for this informative discussion! Please feel free to add any information you’d like our readers to know.

Dooley:

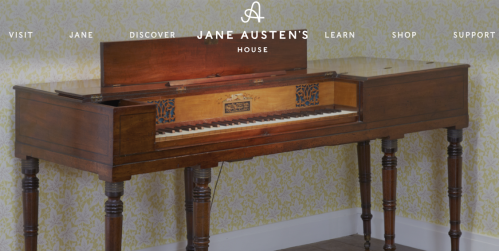

My book is based on the Austen Family Music Books, which is a collection of about 20 albums of music, printed and manuscript, that belonged to various members of the Austen family circle – all female – around the time of Jane Austen’s life, from her teacher, Ann Cawley, to some of her nieces. I concentrated mainly on the books that belonged to her, especially the ones in her own handwriting, but I also look at her relationships with the owners of the other books. They contain a variety of music, both instrumental and vocal, and give an interesting snapshot of the music that was popular at the time for playing at home. There’s more information, including links to collection online, plus some scores I have transcribed and some live recordings I’ve done over the years, at my Jane Austen’s Music website .

Additional information:

Flinders University: Find Dr Dooley’s university profile on this page.

The University of Edinburgh –

- Jane Austen and Scottish Music – “Jane Austen’s surviving music collection includes many songs that are either genuinely Scottish or reflect the fashion for Scottish music in England in her time. In this program a selection of these melodies is presented, either as songs or piano variations, and some links with her novels are suggested.” (Note: Tickets are on sale for a July 22 concert. Gillian Dooley (soprano) and Judith Gore (piano) present ‘Scotch’ and ‘Irish’ Airs from Jane Austen’s collection.)

Synopsis of project proposal:

In my forthcoming book “She Played and Sang: Jane Austen and Music” (Manchester University Press), I include a survey of British song in Austen’s surviving music collection, digitized by Southampton University Library, and in her fiction. So-called ‘Scotch airs’ were enormously popular during Austen’s lifetime. Given Austen’s well-known Jacobite sympathies, it is not surprising that she felt no impulse to resist this musical tide from the north. Her music collection shows that she was drawn to Scottish music, and two of the four songs her young relatives remember her singing in her later years were Scottish: ‘Their groves of sweet myrtle’ and ‘The yellow-haired laddie’ – the other two being respectively French, and English (by an Irish composer). Roger Fiske proposes that one of the reasons for the popularity of Scottish songs was ‘the piquancy of their Scots characteristics’. Other political or ideological reasons might be adduced, but these characteristics do set them apart from the common run of pastoral love songs and help to explain their attraction for Austen. – Enter the site to read the rest of the project description

Listen to/See the Music:

SOUNDCLOUD

Gillian Dooley: 75 tracks, that include:

Angels ever bright and fair – Handel

If grief has any power to kill – Henry Purcell

Colin and Lucy – Tommaso Giordani

Jane Austen – The French Connection

And more!

Gillian Dooley’s YouTube Channel

.

Their Groves of Sweet Myrtle

The Yellow Haired Laddie, instrumental

Book Reviews and the author’s published articles

Reviews of She Played and Sang

- Interlude: Review of She Played and Sang – Jane Austen and Music, By Gillian Dooley, Frances Wilson, March 7, 2024

- GoodReads Review – 5 stars

In Addition:

- The Edinburgh Companion to Jane Austen and the Arts, Edited by Joe Bray, Hannah Moss, Edinburgh University Press

In the introduction, author Gillian Dooley reveals her primary reason for writing a book about music in Austen’s life – that of exploring the “rhetorical link between writing and making music, especially given the musicality of her prose” (P 3). This statement reveals the book’s direction. She quotes Robert K. Wallace in

In the introduction, author Gillian Dooley reveals her primary reason for writing a book about music in Austen’s life – that of exploring the “rhetorical link between writing and making music, especially given the musicality of her prose” (P 3). This statement reveals the book’s direction. She quotes Robert K. Wallace in

This is the time when new books are published ahead of the spring and summer seasons. One offering from Manchester University Press particularly intrigued me. I also included in this post my responses to two books I recently purchased in preparation for a post about the Grand Tour.

This is the time when new books are published ahead of the spring and summer seasons. One offering from Manchester University Press particularly intrigued me. I also included in this post my responses to two books I recently purchased in preparation for a post about the Grand Tour. The Grand Tour of Europe

The Grand Tour of Europe Jane Austen’s Brother Abroad: The Grand Tour Journals of Edward Austen

Jane Austen’s Brother Abroad: The Grand Tour Journals of Edward Austen