Book Review by Brenda S. Cox

“It’s an inspiring example [of growing older]—to be amazed, amused, and to laugh while choosing to wear just what you wanted.”—Janet Todd, in Living with Jane Austen, talks about Jane “writing little spoofs and funny letters to entertain her nieces and nephews,” in her late thirties, when she can dress for her own comfort rather than having to please others.

Many authors celebrated Austen’s 250th birthday with books giving their own slants on our beloved Jane Austen. Two university professors attracted my attention because of their high qualifications combined with reader-friendly writing. I knew Janet Todd’s name as the general editor of the authoritative Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jane Austen, the version I quote from for serious Austen articles. I knew Devoney Looser’s name as a vibrant speaker at JASNA AGMs. I enjoyed personally meeting and hearing both of them in September, one in England, one in Atlanta, Georgia. I enjoyed their talks so much that since then I’ve read both their books. Today I’ll review Todd’s book, and in a few days I’ll review Looser’s book.

Living with Jane Austen, by Janet Todd

Living with Jane Austen by Janet Todd is like a fun ramble in the countryside with the author. She explores words, ideas, themes, connections, and sidelights of Austen’s novels and letters. Her introduction examines connections between her life and Austen’s, and the meanings of ‘memory’ in the novels. The other chapters cover an extensive array of topics. I’ll give you a quote from each chapter as a little taste, to whet your appetite.

Chapters in Living with Jane Austen

The Brightness of Pemberley

(mostly on the significance and implications of country estates)

“In the novels published after Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen will give her heroines many comfortable homes, though none so grand as Pemberley. In the last, Persuasion, however, she lets her heroine be married with no home to go to at all. . . . In this novel, the distinction is clear at least between a house and a home: the sailors can make a home on a boat, or in a rental for a few months in Lyme Regis, but Anne’s father, the landowner Sir Walter, can’t make one anywhere. . . . Anne Elliot understands that people are more important than property, and that they are not at all the same thing” (37).

The Darkness of Darcy

(mostly on patriarchy, with some extensive comparisons with feminist Mary Wollstonecraft’s writings and life)

“Is Darcy not Patriarchy itself, with all its glittering, merciless, unequal glamour?” (53) “The fact that as readers we delight in what both Darcy and Elizabeth have gained through the great property is the smudge of darkness I find at the heart of this lightest and brightest of novels” (57).

“Sir Thomas [Bertram of MP] is another patriarch in a big house frightening the vitality out of his dependants. Could he be Mr. Darcy, grown older, if he’d been foolish enough to marry Caroline Bingley instead of Elizabeth Bennet?” (or, I would say, if he’d married Anne de Bourgh . . . )

Talking and Not Talking

(mostly about the right and the wrong words, class, and wit)

“I revere Emma but something disturbs me. . . . Anyone who fears she might be an interloper, the not-quite-proper arrival in a new place will understand. . . . Mrs. Elton dropped abruptly into Highbury; loud Mrs. Elton, not quite ‘a lady’” (59). Ooh, can we relate to Mrs. Elton, of all people? Moving right along . . .

“As aware of rank as snobbish Emma, Elizabeth takes an opposite tack: where Emma disparages those beneath her—the Martins, Coleses and Eltons—Elizabeth mocks the ranks above her” (79).

Making Patterns

(patterns and connections that bring us deeper; includes comparisons of Northanger Abbey and Sanditon, Austen’s first and last written novels.)

“Austen’s late revising of Northanger Abbey possibly triggered the whole project of ‘Sanditon’. In which case, she’d be reversing the sexes: using the Henry Tilney—Catherine Morland dynamic to create (in the absence of Sydney Parker) the sober-minded Charlotte and fiction-addled, quixotic Sir Edward. Unlikely though it sounds, perhaps, after the gentleman has been chastened and reformed rather than the lady, these two might make a match. We’ll never know.”

Poor Nerves

(connections of mind and body; mental stress causing physical symptoms)

“Yes, the sun was hot, yes, Fanny [Price] had a headache. But it’s difficult for the reader not to see other factors at work. Fanny forgets to lock the spare room in the parsonage. We wouldn’t expect her to be so careless. Was she . . . already letting jealousy infect her mind because Edmund was away with Mary Crawford?” (115)

The Unruly Body

(illness, nursing, the skin, teeth, and headaches in Austen’s life and novels)

“If you want advice about teeth from Jane Austen, there it is: stay away from dentists” (147).

Into Nature

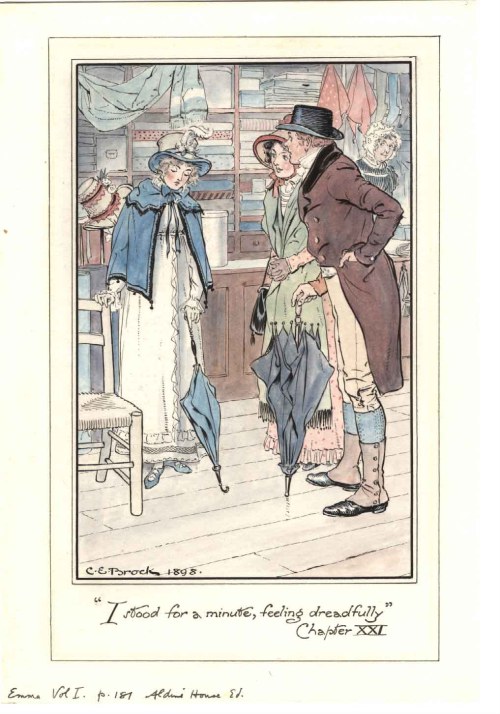

(weather, umbrellas, estate improvements, long walks)

“Dramatised in the novels, the Church of England becomes a matter of sermons and parsonages, ordination and tithes, but in the letters, underneath the worldly concerns, the Church emerges as a way of life, of experiencing life, like noting when Spring arrives, Autumn fades or Christmas approaches. It’s a very ‘moderate’ seasonal English way of being religious” (165).

Giving and Taking Advice

(advice from conduct books; advice in love; guidebook advice; writing advice)

Virginia Woolf wrote that ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction,’ but Austen’s experience was different. Based on Austen:

“If you intend to write anything, best not follow Virginia Woolf and wait for your own room and money and certainly not depend on inspiration, but do avoid much housekeeping” (185).

Being in the Moment

(moments of stillness in Austen, Wollstonecraft, Wordsworth, Cowper; comfortable moments with good food)

“In the finished novels, there are moments when the heroines step aside. . . Without being overtly religious, these moments, prayerful and cloistered, resemble a stoical Christian meditative state in which the mind becomes stilled. Perhaps the woman is simply ‘reasoning with herself’, perhaps trying to gain composure to cope with a disruptive emotion or endeavouring to arrange feelings so they can be investigated later—or just accepting emptiness” (199).

How to Die

(death in Austen’s fiction and in her life)

After quoting Cassandra’s comments on Austen’s death, Todd summarizes: “Fortitude in life, patience in death, kindness and gratitude in both” (232).

Afterword

(One of the gifts Austen has given her is an appreciation of home.)

“Jane Austen . . . might have preferred to be in Chawton churchyard near the cottage where she’d now be lying with her mother and sister. It might have seemed more like home” (235).

These are just a few of the delightful tidbits I appreciated. Some references to other books of the time were less familiar, but still interesting. The book is full of fascinating insights, connections, and thoughts about Austen’s life, words, and world. I recommend Living with Jane Austen by Janet Todd. (UK link)

For a further perspective, read “Jane Austen and Me.”

In a few days we’ll look at a different perspective on Austen, Devoney Looser’s Wild for Austen.

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.