Fire!

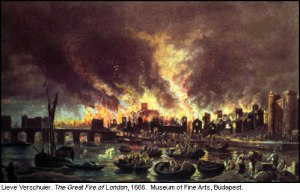

Can there be a more frightening word in Georgian London? The great fire in 1666 changed the landscape of that city forever. Once a densely packed city riddled with overcrowded, wood-timbered houses and dark, narrow lanes, the fire led the way to a change in building regulations that ushered in brick and stone edifices, wider streets, and public squares. Even with improvements, a fire still presented a horrifically dangerous situation.

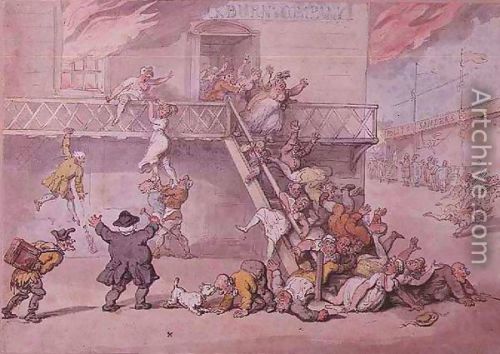

Thomas Rowlandson captures the scene with such realism in “Inn Yard on Fire” that one can smell the smoke and fear, and hear the horses neighing, people screaming, furniture breaking, and wagon wheels squealing as guests and staff run around trying to save themselves, their possessions, and each other.

Panic and pandemonium ensue. A man contemplates tossing a mirror from the second story, another pours his ineffectual chamber pot over the flames. A side table has been tossed through the window, while an anxious woman descends a ladder.

People are in various states of dress and undress. Some help others, some are overcome with panic. A disabled man is carried from danger in a wheel barrow, while a groom tries to calm two terrified horses.

Elements in Rowlandson’s cartoon show a direct association with classical language and Tobias Smollet. The young man saving the girl in distress is reminiscent of Giambologna’s statue of the Rape of the Sabine Women, as well as Peregrine Pickle’s heroic actions towards Emilia.

Peregrine Pickle saves Emilia. Image @A World History of Art

Once a fire had gained as much ground as depicted in this illustration, there was little chance of saving the building. Rowlandson shows some people carrying out their belongings, while others were barely able to get dressed. By now an alarm had probably been sounded in the community. Bucket brigades, in which people were arrayed in long lines to the nearest well and passed buckets in a continuous motion, could probably put out a minor fire, but not one of this magnitude. In the 1800s, almost 150 years after the great fire, there was still no centralized fire brigade.

In 1680, a property developer named Nicholas Barbon introduced the first fire insurance, which initially insured buildings but not furniture, fittings, or goods. Insurance companies began to proliferate and formed private fire brigades to protect their customers’ property.

In Rowlandson’s cartoon the most the inn keeper can hope for is that the brigade arrives in time to save his structure – if he is insured. This was easier said than done, for many of London’s streets were not named, since many people could not read, and insured properties were difficult to find.

In the early 1800s the fire mark was developed. These plaques, sometimes brightly painted, would signal which properties were protected by insurance firms. Each fire brigade had its own unique plaque.

If a fire started, the Fire Brigade was called. They looked for the fire mark and, provided it was the right one, the fire would be dealt with. Often the buildings were left to burn until the right company attended! Many of these insurance companies were to merge, including those of London, which merged in 1833 to form The London Fire Engine Establishment, whose first Fire Chief was James Braidwood. Braidwood had come to London after holding the position of the Chief Officer of Edinburgh Fire brigade. Edinburgh’s authorities had formed the first properly organised brigade in 1824. – History of the UK Fire and Rescue Service

There were quite a few fire brigades operating in London in the early 19th century and competition was keen. The companies hired sailors and watermen as part-time employees. An advantage of serving in this position was that these men were protected from being pressed into service, a not inconsiderable benefit during the Napoleonic wars.

Buildings that had no insurance protection were left to burn, although attempts were made to save the surrounding buildings. Firemarks were essential to identify insured buildings:

Designs included, for Sun Fire Office: a large sun with a face; the Royal Exchange Assurance: their building; and Phoenix: obviously Phoenix rising from the ashes. Later fire marks were made of tin, copper, or similar material. These are more often called fire plates. They were more an advertising medium as most do not have a policy number stamped upon them. – Fire Marks: The First Logos of Insurance Companies

Illustration from Ackermann’s ”Microcosm of London” (1808) drawn by Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin. Firefighters are tackling a fire which has broken out in houses at the Blackfriars Bridge. Teams of men operate hand pumped equipment. Image @Wikipedia

In 1833 companies in London merged to form The London Fire Engine Establishment, the first step to the various fire brigades being taken over by local government.

The Burning of Drury Lane Theatre from Westminster Bridge 1809. Artist unknown. Image property of the Museum of London.

Equipment was still very basic but in 1721, Richard Newsham patented a ‘new water engine for the quenching and extinguishing of fires’. The pump provided a continuous jet of water with more force than before. This new fire engine became a standard until the early 19th century.

The men used the handles to pump the water from a lead-lined trough in the main body of the equipment. The apparatus was quite heavy and difficult to maneuver, but it represented a huge step forward in fire fighting technology. People continually ran back and forth to a water source to fill the trough with water. You could also attach a hose to aim the water to a specific location. During this time, however, hose-making was still in its infancy and many leaked. Water buckets and axes to hack out trapped people and create fire free perimeters were still regarded as standard fire fighting equipment.

The Burning of the Houses of Parliament, 1834 by William Mallord Turner. Such an event must have provided a spectacular yet horrifying scene for onlookers.

Steam powered appliances were first introduced in the 1850s, allowing a greater quantity of water to be guided onto a fire. With the invention of the internal combustion engine, these appliances were replaced in the early 1900s.

James Pollard (British, 1797-1867) London fire engines: The noble protectors of lives and property, 1823. Image @Olympia Art Antiques

This image by James Pollard, and engraved by R. Reeve, shows several insurance brigades hurrying to a fire.

The firemen, of the time, had little training and wore brightly coloured uniforms to distinguish themselves between the different brigades. During large fires they would become very tired through continual pumping of the appliances, and would offer bystanders ‘beer tokens’ in return for their help. – Insurance Firemen and their Equipment

Each company provided different liveries for their men, so that the fire fighters could easily be identified with a particular firm.All insurance firemen wore a large badge on their shoulder to show which insurance company they worked for.

More on the topic:

- How has London Coped With Fires Since 1666?, PDF Document, Museum of London

- London’s Burning, Museum of London

- Not With their Property But with Their Lives

- Rowlandson Image: Lewis Walpole Library

- From Fire Marks to James Braid Wood, the Surveyor who set up the Fire Brigade

- The Wooden Fire Pumper

- The History of Firefighting

(sighs with pleasure) I knew you’d include the Turner.

Excellent post. The pictures are beautiful.

I still wonder how they managed to get across the message that there was a fire! Without telephones, they must have needed to send someone with the message. And if it broke out at night time … !!!

Good point! I believe that word of mouth was the best way to get the word out. I found no sources (there probably are some) that described how many fire brigades one insurance company would field and what the contingency plans were in the case of two fires burning at the same time.

Great pictures. Thank you for the information.

Very good, thanks for this. Throughout most of history, London was just one big fire waiting to happen, which it did of course. Frequently. Would highly recommend London Fire Brigade Museum in Southwark. Also, I am lucky enough to have a review copy of Caroline Shenton’s new book on the Houses of Parliament fire of 1834 (the Turner one), out on 9 August, highly recommended.

Great post and super pictures – thank you. I especially liked the Sabine women allusion. My own favourite name for an 18th century fire contraption was the patented ‘New sucking worm engine’. Bigger fires by the early 19th century would have been fought in London from water supplies running in wooden pipes under the street, into which the engines could place their hoses via street plugs (hydrants) and draw the water into the engine tanks through the pumping mechanism. Each parish was required by law to have an engine too so often this was the first local response, alerted by passersby and ‘Fire!’ must have been a frequent shout on the London streets. The 1834 fire at Parliament was unusual in that private companies did turn out to help voluntarily, but if a paying client had called them out too, they would have had to go. As Mike kindly mentions above, my book “The Day Parliament Burned Down” is about to be published and there is more in there about the politics and mechanics of firefighting right at the end of the Georgian period if anyone is interested further.

Delightful read on a subject that I had not given much consideration to before now.

I have been to a number of smaller towns where the fire engine was kept in the church tower – that was the case at Tonbridge, where George Austen grew up.

i am surprised you did not mention my ancestor John Lofting who was the inventor of the New Sucking Worm Fire Engine predating all the people you have named. There is a print in the British Museum reg G,10.76 no AN437481 illustrating both its use and with a picture of John. He took out a patent see London Gazette March 17th 1691 for this (reign of William & Mary)

Hi Deb, thank you for the information! When I wrote this post I knew next to nothing about fire fighting during that era. I appreciate your stopping by.