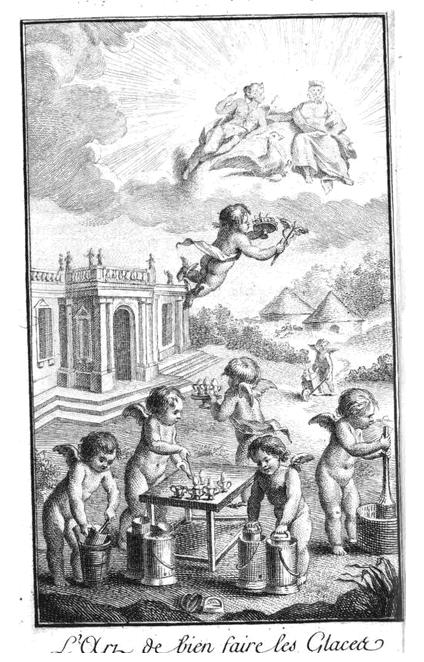

This frontispiece from L’Art de bien faire les glaces d’office, a book by M. Emy, an 18th century French confectioner, about whom very little is known, depicts how ices and ice cream were made at the time.

Buckets filled with ice and salt held covered metal freezing pots that contained the ice cream mixtures. As the mixture froze, the pots were taken out occasionally to be shaken. The ice cream was scraped from the sides of the pots and stirred. When the mixture was ready, it was placed in decorative molds and served almost immediately. You can see the all the steps of ice cream making in the above image, with ice being delivered from ice houses in the background, and cherubs tending to the freezing mixture, while another hastens to the main house to serve the ices before they melt.

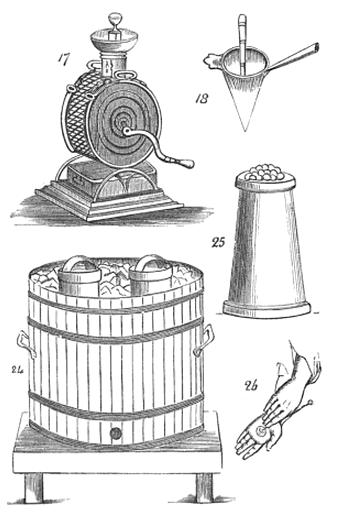

Confectioners tools from Gunter’s modern confectioner by William Jeanes. Figure 18 represents a copper funnel. Figure 24 is an oval tub surrounded with ice and salt and containing tow freezing pewter pots. At the bottom is a plug to let out water. Figure 25 represents a Bomba ice mould, which has the impression of fruit and holds from four to six pints each. Figure 26 shows how the hands are positioned whilst modelling flowers.

The process was expensive, for hauling and storing great blocks of ice was a laborious process that began in winter. The ice was stored in ice houses that were dug deep into the ground to keep the blocks from melting even in summer.

The Eglinton Ice House being filled with ice. Eglinton Castle, Kilwinning, Scotland. Image @ Wikipedia

Only the rich were able to afford this luxury food to any extent until the mid-19th century, when Carlo Gatti began importing ice in large quantities to London from Norway.

The first references to making ice cream harken back to ancient Rome and China. By the mid 18th century, French, Italian, and British chefs had published cookbooks with recipes for ices and ice creams. Specialty confectioner’s shops that offered ices and ice cream began to pop up in London: the most famous of these became to be known as Gunter’s Tea Shop, which survived in one form or another until quite recently.

In 1757 an Italian pastry cook named Domenico Negri opened a confectionery shop at 7-8 Berkeley Square under the sign of “The Pot and Pineapple”. At that time, the pineapple was a symbol of luxury and used extensively as a logo for confectioners. Negri’s impressive trade card not only featured a pineapple, but it advertised that he was in the business of making English, French, and Italian wet and dry sweetmeats. The confectioner’s art required as much precision and craft as a sculptor or silversmith. Equipment for refining sugar resembled those of a foundry, including specialized pans for melting, devices that calibrated heating and cooling, and a variety of molds to create shapes for chilled custards and ice cream, frozen mousses, jellied fruit, and candies and caramels. Negri’s shop sold

Cedrati and Bergamot Chips, Naples … Syrup of Capilaire, orgeate and Marsh mallow … All sorts of Ice, Fruits and Creams in the best Italian manner’. It also sold diavolini, or little icing-sugar drops scented with violet, barberry, peppermint, chocolate and neroli made from the blossom of bitter orange. For those who could not stretch to the luxury of shop-bought produce but who could afford a book of recipes, a long struggle with the complexities of sugar science ensued.” – Taste, Kate Culquohon

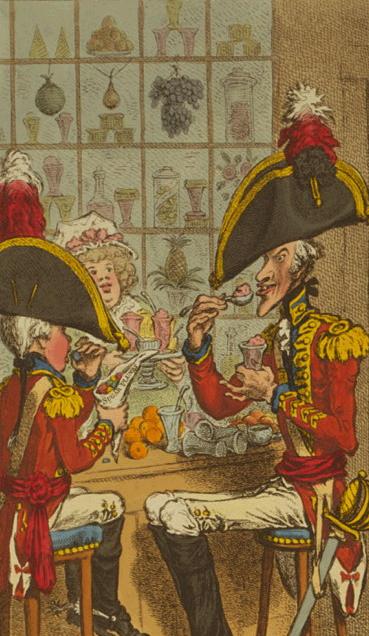

No Regency image of The Pot and Pineapple or Gunter’s exists. This is a detail of a James Gillray cartoon of soldiers eating in a confectioner’s shops, 1797. Image @Library of Congress

As the chefs of the era attest in their recipes, the taste in ice cream seemed to change with each generation. M. Emy made a glace de creme aux fromages that was flavored with grated parmesan and Gruyere cheeses. Joseph Gillier made an artichoke ice cream and a fromage de parmesan with grated Parmesan, coriander, cinnamon, and cloves frozen in a mold shaped like a wedge of parmesan cheese.

Ivan Day image of ice groups. One can see his recreation of the incredible detail that confectioners were able to create for their wealthy clients. Ivan Day, Ices and Frozen Desserts

Flower flavors were also common – violets, orange flowers, jasmine roses, and elder flowers – were used in ices. The vanilla bean, although appreciated for its agreeable flavor, did not rise in popularity until Victorian times. Negri must have done a booming business selling syrups, candied fruits, cakes, biscuits, ices, delicate sugar spun fantasies, and elaborate table decorations that showcased his deserts, for his shop survived many decades.

Twenty years after starting his Berkeley Square establishment (1777), Negri took in a business partner named James Gunter. The Gunter family, which had both Catholic and Protestant members, had lived in Abergaveny in Wales for generations. (Read a fascinating history about the family at this site, Last Welsh Martyr.)

The shop employed famous apprentices like Frederic Nutt, William Jarrin, and William Jeanes, who would go on to write their own cookbooks. All proudly noted their association with the shop. Interestingly, William Gunter, who was James’s son, wrote the most frivolous cookbook, Gunter’s Confectioner’s Oracle (published in 1830), in which he gossiped, name-dropped, and included some illogical details.

One section of the book was supposed to be a dictionary of raw materials in use by confectioners. It started with A for apple, and skipped B because it ‘is to us an empty letter.’ C was a fourteen-page treatise on coffee, in French … Gunter did not name its source…The dictionary skipped D and E. The letter F was for flour. Then Gunter wrote, ‘I now skip a number of useless letters until I arrive at P.” – ‘Of Sugars and Snow: A history of ice-cream making’, Jeri Quinzio, University of California Press, 2009, p. 65.

With two men at the helm, The Pot and Pineapple flourished and by 1799 Gunter had become its sole proprietor, changing the name to Gunter’s Tea Shop. (I tried to find Negri’s birth and death dates, and can only surmise that he must have retired or died when Gunter took over.)

Berkeley Square was uniquely situated to appeal to the upper crust. Many notable people lived there – Beau Brummell at #42 in 1792; Lord Clive the founder of the British Empire in India, lived at #45 until he killed himself in 1774; and Horace Walpole, whose letters give the record of fashionable society of his day, lived at #11 until he died in 1797. (Nooks and Corners of Old England.) The square was described as a

frontier land between West-end trade and West-end nobility. The east side is half shops, on the northern there is an hotel. Confectioners and stationers here confront peers and baronets.” – Every Saturday: A Journal of Choice Reading, Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

By the early 19th century, Gunter’s ices had become so fashionable that the Beau Monde, many of whom already resided in tony Mayfair, made it a custom to stop by the shop for a cool ice during carriage rides.

A custom grew up that the ices were eaten, not in the shop, but in the Square itself; ladies would remain in their carriages under the trees, their escorts leaning against the railings near them, while the waiters dodged across the road with their orders. For many years, when it was considered not done for a lady to be seen alone with a gentleman at a place of refreshment in the afternoon, it was perfectly respectable for them to be seen at Gunter’s Tea Shop.- Encyclopedia of London

View from the shop today at #7 to the green space of Berkeley Square. The plane trees are among the oldest in central London, planted in 1789 by Edward Bouverie. One can imagine the carriages parked in this area, with waiters scurrying back and forth. (Few of the original buildings still stand today.)

It seemed that a rendezvous at Gunter’s in an open carriage would not harm a gently bred lady’s reputation! One can also imagine waiters running at a full clip across the street on hot days when ices began to melt as soon as they were released from their molds!

Gunter’s was also known for its catering business and beautifully decorated cakes. In 1811, the Duchess of Bedford’s and Mrs. Calvert’s ball suppers featured the shop’s confectionery, a tradition followed by many a society lady, I am sure.

James Gunter’s success allowed him to purchase land in Earl’s Court, which was largely farmland in the 18th century.

Normand House, built in Earl’s Court in the 17th century, is now demolished. Image @MyEarlsCourt.com

Gunter bought the tracts of land so he could run a market gardening business. The produce – fruits, vegetables and flowers – was taken daily by horse-drawn wagons to Covent Garden to be sold. Gunter also

bought Earls Court Lodge (near the present Barkston Gardens) which was to be the Gunters’ family home for the next 60 years. This was one of the few substantial houses in the area. (The aristocratic neighbours at nearby Earls Court House, who weren’t keen on having a cake shop owner next door, called it “Currant-Jelly Hall”).” – The Gunter Estate

Gunter died in 1819 and his son Robert (1783-1852), who studied confectionery in Paris, took over the business. Robert hired his cousin John as a partner in 1837, ensuring that the business would stay in the family for several generations. Gunter’sTea Shop moved to Curzon Street when the east side of Berkeley Square was rebuilt in 1936-37. The shop closed in its new location in 1956, although the catering business continued for another 20 years in Bryanston Square. More on the topic:

- Former Gunter family mansion

- Berkeley Square British History Online

- Handbook of London Berkeley Square

- Gunter’s Modern Confectioner, William Jeanes, 1870 Google

- The complete confectioner: or, The whole art of confectionary made easy: also receipts for home-made wines, cordials, French and Italian liqueurs, &c (Google eBook)…By Frederick Nutt J.-J. Machet Printed for S. Leigh and Baldwin Cradock, and Joy, 1819. Here is the 1807 edition online at the Open Library. “All conscientious apprentices would keep a journal of all recipes seen and done, as they went about learning their trade. In this respect Nutt was no exception. One aspect of the manuscript that it is quite startling is how little editing happened between the manuscript and the published first edition of ‘The Complete Confectioner’. – Old Cookbooks

- Food History Jottings: Queen Cakes and Cup Cakes

- Bill Head of Domenico Negri, Pot and Pineapple: British Museum

- Trade Card: Domenico Negri, British Museum

- The Sweetest Things in Life

- Ivan Day, Ices and Frozen Desserts

- Ice Imports from Norway to London

- The Art of Confectionary: Ivan Day

- Georgian Ices and Victorian Bombes: Ivan Day

- Taste: The Story of Britain through Its Cooking By Kate Colquhoun, p 232

- L’Art de bien faire les glaces (The Art of Making Ice Cream) by M. Emy, 1768,

- Gunter’s Confectioner’s Oracle, by William Gunter 1830

- Of Sugar and Snow: A History of the Ice Cream Making, By Jeri Quinzio, 2009, p 60-62, 65-67

- The London Encyclopaedia (3rd Edition) (Google eBook), Christopher Hibbert Ben Weinreb, John & Julia Keay, 2011, p. 365

- Harvest of the cold months: social history of ice and ices, Elizabeth David, Faber and Faber, 2011

- Bartleby: Ices, Ice Creams, and Other Frozen Desserts.

Please Note: None of the advertisements that sit below this post are mine. They are from WordPress. I make no money from this blog.

![TALLIS, JOHN. TALLIS'S LONDON STREET VIEWS, EXHIBITING UPWARDS OF ONE HUNDRED BUILDINGS IN EACH NUMBER, ELEGANTLY ENGRAVED ON STEEL, WITH A COMMERCIAL DIRECTORY CORRECTED EVERY MONTH, THE WHOLE FORMING A COMPLETE STRANGER'S GUIDE THROUGH LONDON... THE PUBLIC BUILDINGS, PLACES OF AMUSEMENT, TRADESMEN'S SHOPS, NAME AND TRADE OF EVERY OCCUPANT. LONDON, N.D. [CA. 1840].](https://janeaustensworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/tallis-fleetstreet-christies.jpg?w=500&h=320)