Reviewed by Brenda S. Cox

The Journal of a Georgian Gentleman: The Life and Times of Richard Hall, 1729-1801 provides fascinating insights into Jane Austen’s England.

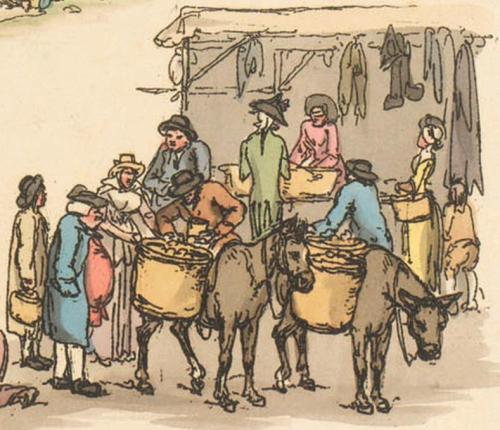

Richard Hall was a tradesman, a hosier who made stockings in a shop near London Bridge. Like the Coles in Emma, he “was of low origin, in trade,” but moved up in society as he became wealthier. Hall accumulated his fortune through hard work, marriage, inheritance, and investments. From selling silk stockings, he moved into selling fine fabrics, silver buckles, and other fashionable accessories. Hall eventually owned several estates, and retired as a country gentleman.

I asked the author, Mike Rendell, to tell us more about how he wrote this book.

Rendell says he inherited “a vast pile of old family papers, . . . stuffed into tea chests and boxes in the back of the garage” in his grandmother’s house. He focused on the papers related to Richard Hall and found it “a fascinating voyage of discovery.”

Rendell continues, “For instance, if he [Richard Hall] recorded in his diary that he had ‘visited the museum’ it made me research the origins of the British Museum, realizing that he was one of the earliest visitors. Which led on to researching what he might have seen, etc.”

He adds, “Writing my first book opened my eyes to a great deal about the world in which Jane [Austen] was brought up. I love her works – especially P&P and I must admit to binge-watching the entire BBC version in a single sitting, at least twice a year!”

In the context of Richard Hall’s story, Rendell tells us about many aspects of life in the eighteenth century, based on his extensive research. For example:

Religion

Richard Hall was a Baptist, one of the Dissenter (non-Church of England) groups in Austen’s England. This meant that even though Hall loved learning, he was not able to attend university. Oxford and Cambridge, the two English universities, would not give degrees to Dissenters. Hall could have studied in Holland, but his family decided to bring him directly into their hosiery business instead.

Richard Hall’s grandfather and father were Baptists, and Richard attended a Baptist church and listened to sermons by the famous Baptist preacher Dr. John Gill for many years. Richard also collected printed sermons by Dr. Gill. However, it was not until Richard was 36 that he “gave in his experience” and was baptized. Rendell explains that “giving in his experience” meant “explaining before the whole church at Carter Lane in Southwark how he had come to faith in Christ.”

Some of the leaders of the English Baptists of the time are part of Hall’s story, as well as disputes and divisions between Baptist churches.

Hall sometimes attended Anglican churches, and was even a churchwarden for a time. Rendell comments, “The fact that he was a Baptist did not mean that he was unwilling to attend Church of England services – just as long as the gospel was being preached.”

Methodists were another important movement in Hall’s England, though they were still part of the Anglican Church for most of Hall’s lifetime. One of Hall’s relatives, William Seward, became an early Methodist minister, preaching to open-air crowds. Rendell writes that Seward “died after being hit by a stone on the back of the head while preaching to a crowd at Hay-on-Wye, on 22 October 1740 – one of the first Methodist martyrs.”

Silhouette of Richard Hall, probably “taken” (cut out) by his daughter Martha. In 1777 Martha “gave her experience” and was baptized in a Baptist church, as her father had done.

Science

Rendell often explains advances in science that affected Hall’s life (and Jane Austen’s). He writes, “By the standards of his day . . . Richard was a well-educated man. Above all, he was a product of his time – there was a thirst for knowledge all around Richard as he grew up. There were new ideas in religion, in philosophy, in art and in architecture. This was the age of the grand tour, of trade developments with the Far East, and a new awareness of the planets and astronomy as well as an interest in chemistry and physics. It was a time when the landed gentry were experimenting with new farming methods – inspired by ‘Turnip’ Townsend and Jethro Tull – and where a nascent industrial revolution was making its faltering first steps.” Richard wrote down many scientific “facts”—or fictions—some of which are listed in an appendix.

Surprisingly, Richard Hall records several times that he saw the Aurora Borealis in southern England. Apparently, the aurora was sighted many times in Austen’s England, though it has since migrated northward.

Rendell also tells us about an invention that greatly improved transportation: the development of macadam roads. These were named for the Scotsman John McAdam who invented the process. When bitumen (tar) was added in the nineteenth century, such roads were called “tar-macadamised”: a word eventually shortened to “tarmac.”

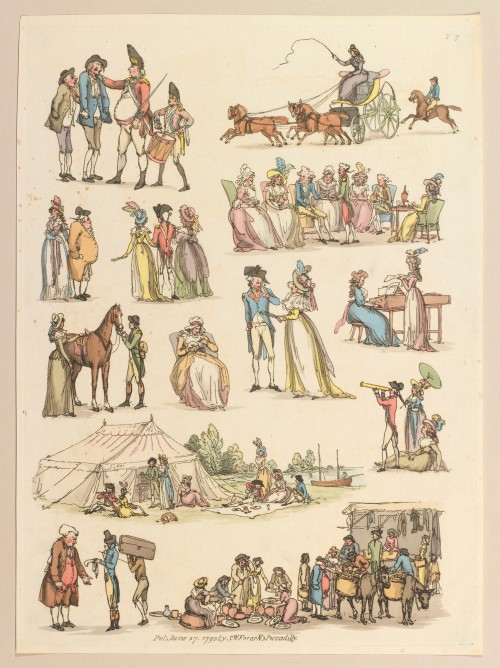

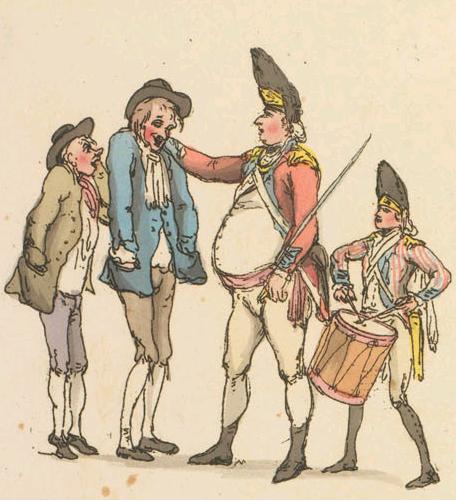

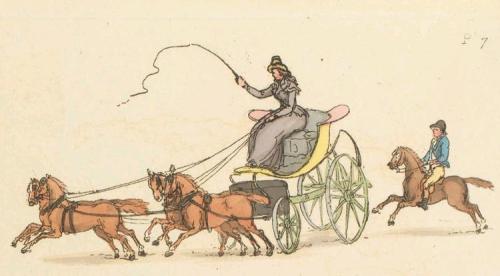

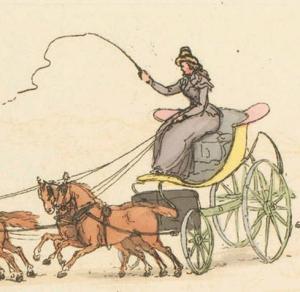

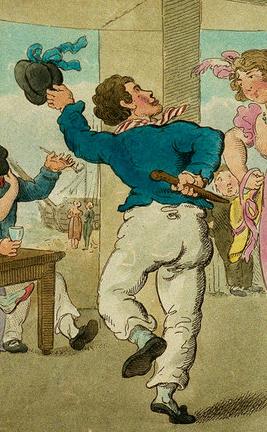

Travel was quite an adventure in Austen’s time. Richard Hall made this detailed paper cutout of a coach and four, showing one of the fastest means of transportation available at the time. Hall also did cutouts of a coach and four about to crash because of a boulder in the road, and a one-horse coach being held up by a highwayman.

Medicine

Richard Hall’s small daughter was inoculated against smallpox, which meant she was given the actual disease. She had “between two and three hundred pustules.” But Richard writes that about three weeks later, “Through the goodness of God . . . the Dear Baby finally recovered from inoculation.”

About ten years later, inoculation–giving the patient a hopefully mild case of smallpox–was replaced by vaccination. Dr. Edward Jenner developed this technique, where patients were given cowpox rather than smallpox to develop their immunity. However, Jenner became a member of the Royal Society (of scientists) not for his work on vaccination, but for his observations of cuckoos and their habits! He also experimented with hydrogen-filled balloons. The “naturalists” (not yet called “scientists”) of this age were interested in topics that nowadays we would separate into many different branches of science.

When Hall’s first wife, Eleanor, died of a stroke, he cut this tiny Chinese pagoda in memoriam, with her name, age, and date of death. Rendell says it is “like

lace. It is just an inch and a quarter across and most probably fitted in between the outer and inner cases of his pocket watch. In other words it was worn next to his heart. Very romantic!”

Weather

Hall also noted the weather. In 1783 he refers often “to a stifling heat, a constant haze, and to huge electrical storms which illuminated the ash cloud in a fearsome manner.” These were the effects of a huge volcanic eruption in Iceland, the Laki volcano. This eruption, the most catastrophic in history, caused an estimated two million deaths worldwide, and wiped out a quarter of the population of Iceland. In England, the harvest failed, cattle died, and about 23,000 people died of lung damage and respiratory failure.

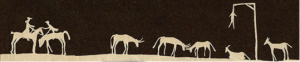

Highwaymen were another danger in Austen’s England. In this paper cutting by Richard Hall, a criminal, possibly a highwayman, hangs on the gallows while spectators are unconcerned.

Language

Richard Hall wrote a list for himself of words that sound different than they look. He gives the spelling, then the pronunciation, which helps us see how people in his area and level of society spoke. A few examples:

Apron—Apurn

Chaise—Shaze

Cucumber—Cowcumber

Sheriff—Shreeve

Birmingham—Brummijum

Nurse—Nus

Dictionary—Dixnary

The history of some words are also explained. For example, the word “gossip” was a contraction of “God’s siblings.” Such women helped mothers in childbirth. The “gossips” offered sympathy, kept men away, and chattered in order to keep up the mother’s spirits throughout her labor.

Museums and Exhibitions

Rendell describes several museums and exhibitions that Hall visited. One of the most intriguing is Cox’s Museum, which Hall and his wife visited the year Austen was born. It featured rooms full of “bejewelled automata.” The most famous was a life-size silver swan, still a popular exhibit at the Bowes Museum in Durham (northern England). The Museum says it “rests on a stream made of twisted glass rods interspersed with silver fish. When the mechanism is wound up, the glass rods rotate, the music begins, and the Swan twists its head to the left and right and appears to preen its back. It then appears to sight a fish in the water below and bends down to catch it, which it then swallows as the music stops and it resumes its upright position.” No less a personage than Mark Twain admired this swan and wrote about it in The Innocents Abroad.

Richard Hall’s upbringing stressed values which still resonate with many people today. Rendell writes, “. . .from an early age it had been instilled into Richard that there were only three things which could help stop the fall into the abyss of poverty, sickness and death. The first was a strong belief in the Lord, and that without faith you got nowhere. The second was the importance of education. The third was that you got nothing without working hard for it. These were the cornerstones of his upbringing – and of the whole of his subsequent life.”

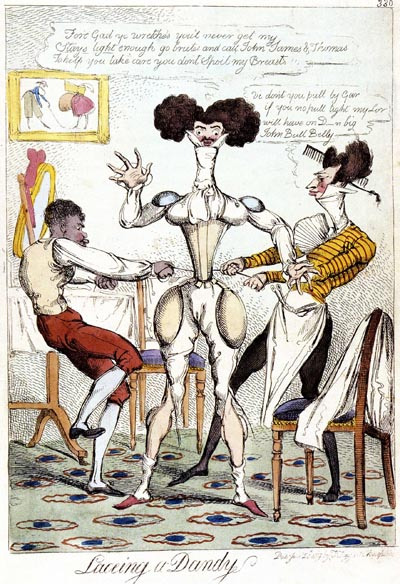

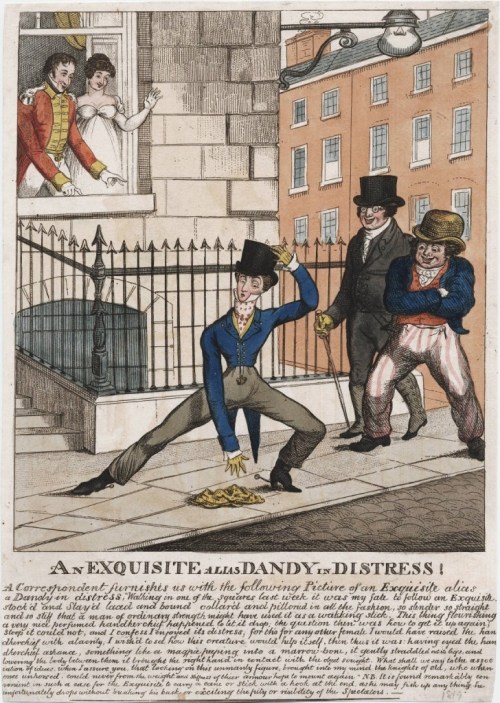

Richard Hall was an artist of paper cutting. He cut out everyday objects and scenes. Many, like this finely-done rapier, were found among his books and journals.

And Much More

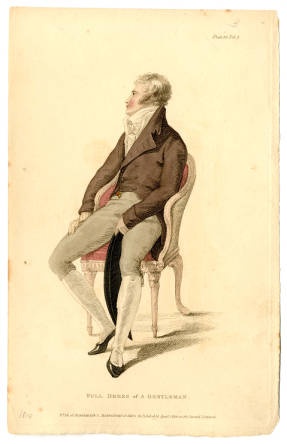

The Journal of a Georgian Gentleman is full of treasures for those of us who love reading about Jane Austen’s time period. We learn about guilds, clothing, food, disasters, transportation, prices, medical advances, explorers, and much more.

To Rendell, Richard Hall “came across as a bit of a joyless, pious individual but then I thought: hang on, he had to face exactly the same problems as we do today – illness, worries about the business, problems with a son who was a mischief maker at school, problems with the drains etc etc. When he re-married he fell out with his children because they didn’t approve of his new bride – and they excommunicated him [avoided and ignored him] for the rest of his life. In that sense his life was just as much of a mess as the ones we lead today!”

While Rendell originally wrote this story for his own family, when he decided to make it widely available he found he needed to promote it. He ended up in a surprising job. He says, “I had never before tried public speaking but quickly found that I loved it – and ended up with a totally new ‘career’ as a cruise ship lecturer (when Covid 19 permits!) travelling the world and talking about everyday life in the 18th Century. . . . These talks include talks about Jane Austen – in particular about the different adaptations, prequels, sequels, etc. of Pride and Prejudice – as well as talks about the venues used in the various films of Jane’s books. I also write articles for Jane Austen’s Regency World. . . . One thing led to another and I have now had a dozen books published, with two more in the pipeline.”

Mike Rendell’s books include topics such as Astley’s Circus (Astley’s is mentioned in Emma and in one of Jane Austen’s letters), Trailblazing Women of the Georgian Era, Pirates and Privateers in the 18th Century, and more. 18th Century Paper Cutting shows the illustrations used in this article, along with other lovely paper cuttings by Richard Hall. See Mike Rendell’s blog at mikerendell.com for more of Mike’s books and blog posts.

The Journal of a Georgian Gentleman is available from amazon in the US and the UK. It is offered on kindle unlimited. If you order a paperback copy from Mike Rendell (Georgiangent on amazon.co.uk), he says, “if anyone orders a copy I will ask (through amazon) and see if they want a personal dedication/signed copy before popping it in the post.” (It is listed there as a hardback but is actually a paperback.)

By the way, Rendell pointed out that Jane Austen’s nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh, also did paper cutting (or silhouettes). You can see examples of James’s work in Life in the Country. There is also a well-known silhouette of Jane’s brother Edward being presented to the Knight family; that one was done by a London artist, William Wellings.

The Journal of a Georgian Gentleman gives us valuable insights into the life of an Austen-era tradesman who became a country gentleman. What would you most like to know about the life of such a person?

___________

Brenda S. Cox blogs about Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen, and is currently working on a book entitled Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. You can also find her on Facebook.