Inquiring readers, It’s such a delight to receive first-hand information from a friend who lives in the U.K. Frequent contributor, Tony Grant, writes about his impressions of seeing the BBC2 special last Sunday entitled Pride and Prejudice: Having a Ball. The scenes were filmed in Chawton House wherein a Regency ball was reconstructed in a way that Jane Austen’s contemporaries knew well, but whose meanings in many instances have been lost to us. I had the privilege of watching the show as well and have interspersed my comments as if Tony and I were engaged in a dialogue. (Italics represent my comments.) Let’s hope this special will be available soon the world over.

Amanda Vickery and Alistair Sooke. Image courtesy of BBC2

It is Winter, 1813.

Amanda Vickery and Alaister Sooke, the art critic for The Daily Telegraph and who also presents art history programmes for the BBC, present this amazing programme. It is one and a half hours long and, being a BBC production, there are no breaks or intermissions.

The programme is a tribute to the two hundredth anniversary of the publication of Pride and Prejudice. The producers have taken the Netherfield Ball as their focus. They did not choose the Merryton Assembly ball, which was a public ball where everybody from the butcher, baker and candlestick maker was eligible to attend. The Netherfield Ball was a more intimate and select affair and by invitation only. One would be assured to rub shoulders with only the best families in the community.

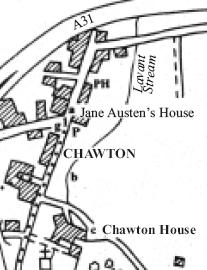

Jane and her sister and mother lived in Chawton Cottage, where Pride and Prejudice was prepared for publication. It was a time when courtship was a serious business. “A woman must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing and drawing,” Jane wrote, and a man had to marry well if he was to secure his dynasty.

Research into costumes, food, dance, music, carriages, conversation and so on focussed on the year 1813.

Filming at night on Chawton House grounds. Image courtesy of Chawton House

The writers and producers consulted and interviewed professors and experts about the minutiae of Georgian life. One professor, Jeanice Brooks at Southampton University, showed Alexander Sooke the very music manuscripts that Jane Austen wrote out by her hand with little cartoon doodlings in the margin.

Jane Austen’s doodle in her music manuscript. Image @BBC2

That was one of the many wow moments for this viewer. (For me too, Tony!)

Popular music was widely collected at the time and summarized for the piano. Jane Austen must have spent hours copying music in her neat hand, for there are quite a number of her music manuscripts still in existence.

Ivan day, historic food expert. Image @BBC2

The food was researched to the minutest degree. Ivan Day and his kitchen staff used Georgian cooking implements, although the Georgian cooking range at Chawton House was not in working order, so they used modern ovens. The recipes were authentic and came from Martha Lloyd’s cook book and other original Georgian documents.

Martha Lloyd’s recipe for white soup, a common dish served at supper dances.

Food denoted status. Game shot on a gentleman’s land was turned into a partridge pie, a symbol of upper class dining. At the Netherfield Ball, Mr. Bingley would be sure to provide only the most excellent food, such as fresh grapes, nectarines and peaches in winter, which would have been expensive to import or grow indoors in hot houses. The grand spectacle of the supper table, with its silver platters, silver dishes, and silver tureens, gave an overall impression of austentation [sic] and of the host’s status.

Ivan Day’s recreation of Solomon’s Temple, a very difficult flummery (Georgian jelly) to recreate. Image @BBC2

Stuart Marsden, an expert in Georgian dances and a former ballet dancer, assembled students from the dance department of Surrey University at Guildford, about twenty miles north of Chawton, to dance at the ball. Although these young dancers were fit and professional, in their Georgian costumes and in the full glare of hundreds of candles, they suffered from heat and encroaching exhaustion as the evening went on.

This fan served to cool the dancer and as a crib sheet, in which the steps of intricate dances were written down. Usually made of paper, few of these fans have survived. As all fans of the Regency know, they also served as the perfect tool for flirtation. Image @BBC2

During the course of the evening, the dancers were supplied with Portugese wine and fortified negus punch. Punch a la Romaine, or Roman punch, was a mixture of rum or brandy with lemon water, lemon meringue and a very hot syrup. It was a sort of creamy iced drink that was 30 or 40 percent alcohol, a Georgian equivalent of a cold Coca Cola that cooled the dancers down between dances.

Punch a la Romaine. By the end of the night the dancers were a little tipsy, shall we say. The spoons used in the production belonged to the Prince Regent and came from Brighton Pavilion. Image @BBC.

Although Chawton House is large, the room where the dance was held seemed rather crowded once all the dancers were assembled. Candles blazed everywhere. The men wore stiff jackets, waistcoats, and neck high cravats. The ladies, whose bosoms were exposed, also wore many layers. They had donned swaths of petticoats under their skirts, and wore long stockings and long gloves. One can imagine that with the press of bodies, heat from the candles, constant exertion in long dance sets, and frequent imbibing of alcohol that the assembly quickly felt heated.

One can see from this image how crowded the ball room was, and how the blaze from 300 candles and hours of exertion might have heated the dancers. I was amazed at the lack of evident sweat.

It was interesting to find out that everybody knew how a long a dance would last from the length and quality of the candles. There were four-hour candles and six-hour candles. For this production eight-hour candles were used.

The finest, most expensive and clean burning candles were made of beeswax. Up to 300 might be used for a ball – quite an expense, for the cost was around £15, or a year’s wages for a manservant. Less expensive (and smokier and stinkier) were tallow candles, which were purchased by the less wealthy. The very poor had to make do with rush sticks, which didn’t last very long.

Peoples’ wealth and position in the upper and gentry classes were evident from the outset. Hierarchy pervaded all strata of Regency society. Social signifiers included the materials used for clothes, their style and the embellishments they had personally chosen for their costumes, the cut of the material and garment, the very buttons they had on their costumes, and so on. These details would reveal not only their status but their personalities too.

Professor Hillary Davidson explains the personal involvement that people had in their clothes, which were hand made and reflected personal taste and input. In addition, the outfits “reflected the range of social rank and social division by cut, color, and texture.” Appearance meant everything at a ball. Many refashioned their frocks from hand-me-downs from an older sister or cousin, creating “hybrid” fashions, for the value of these outfits lay in the material, not the design of the dress. Individual details and features were immediately evident to Jane Austen’s contemporaries, for fashion and jewelry represented a public display of one’s assets. Image @BBC2

Silk would be worn by Miss Bingley, for it was a rich and expensive fabric. Miss Bingley and Miss Hurst would have worn the latest fashions from London, which is quite evident in the film costumes of Pride and Prejudice 1995. Lydia Bennet would have chosen a fine gown, for she was fashion forward for a country girl (and her mama’s favorite), whereas Mrs. Bennet would have worn a print gown with a frilly but modest matronly cap that denoted her status as a woman with some authority. The Bingley sisters would have sneered at the simply styled hybrid dress that the Bennet sisters might have refashioned from a combination of old clothes and newer fabrics. If you were a good needlewoman, such a gown might have been embellished with embroidery, lace, or ribbons.

Simple hybrid dress, much as Elizabeth Bennet might have worn. Notice the coral necklace.

Shoes were changed in the cloak room, for some people walked quite a distance to get to the ball, and even soldiers exchanged their Hessian boots for dancing slippers. Over the course of the evening, delicate dance slippers might be worn down to a thread.

These are Sally Pointer’s historical makeup and rouge pots for rosy cheeks (even for the redcoats, like Wickham). Apply too much color and a lady might be labeled a trollop. Image @BBC2

Everything – one’s clothes, actions, and relationships – how you arrived at the ball – could be read and interpreted. This was one of the main points made by the programme.

It’s not so different today, really, is it Tony? At a glance we can tell who is fashion forward, who is a frump. Whose jewelry reeks of Tiffany’s and who shopped at Walmart. We know from each others speech, friends and business associations, educational background, and other social signifiers who belongs in our social strata and who does not. My mother especially had a keen sense of which of my suitors suited and who did not. Her primary social signifiers were persons of moral character and compassion. It was who that person was inside that mattered, not what they wore or what possessions they had acquired. I suspect that during the Regency such distinctions were also important. Jane Austen was a genius at distinguishing wheat from chaff, and ferreting out the foibles of her contemporaries.

Walking to the ball carrying lanterns. The hooded cloaks reminded me of the medieval era and monks. Image@BBC2

I noticed how most of the actors in the production walked to the ball holding lanterns. Carriages were expensive. If possible, those who had carriages would arrange to pick others up and bring them. If not, the guests walked to the ball. A similar scene was shown in Becoming Jane, where guests arrived on foot and walked along a lane strung with lanterns. Back in those days balls were planned to coincide with a full moon for maximum light at night and for a bit of safety from bandits and robbers. One wonders about such well-laid plans in rainy England, where a blanket of storm clouds would block the moonlight and rain would soil the hems of delicate ball gowns.

The most interesting thing I found from the programme was the meaning of the dance. This Darcy quote, “every savage can dance,” is used to highlight that the dance alludes to something primal. Elizabeth and Darcy have their most unguarded conversation during a dance. Interestingly, the Savage Dance was a craze in 1813 and taken from a song and dance routine from a musical based on Robinson Crusoe.

Balls, to quote Amanda Vickery, were sexual arenas of social interaction. In Pride and Prejudice, Darcy and Elizabeth dance around their sexual attraction for each other. The truth is that in those days single men and well-protected young and unmarried ladies could not spend one moment in private with each other before they were officially engaged. But at a dance they could touch each other (through gloved hands) and flirt and talk at length without a chaperon breathing down their necks. The long dance sets were strenuous and required stamina, however. To quote Amanda Vickery, “The entire ball is hard work, with physical, social, and emotional investment and cost.” The cost being one of expenditure (looking one’s best) and exertion (maintaining one’s stamina.)

Dancing the cotillion. Image @BBC2

Young ladies and young gentlemen practiced and prepared for the balls from childhood on. They had to be good and graceful at dancing to be admired and looked at. This was necessary for their futures, for they were actually dancing for their lives. You were likely to dance with a person from the same rank and expertise: they endured these dances for a very long time with one partner. There were moments of physical contact and movement. Aristocratic young men like Darcy sought strong and accomplished women to be the mother of their children for the sake of inheritance and future generations of their families. Young women needed to attract a good catch for their happiness and futures too. So much effort and hope was invested in the “ball,” for a girl’s future could be sealed at a dance.

No wonder the excitable Lydia Bennet went ballistic when the Netherfield Ball was announced! She was not only man crazy, but she had a competitive streak in her, frequently pitting herself against her older sisters. I was also struck by how much dancing masters could make per person from dance lessons. Every young boy and girl from a respectable family was expected to practice dance steps. It was quite a telling detail for Jane Austen’s contemporary readers that Mr. Collins is a poor dancer and that Mr. Elton exhibited such ungentlemanly conduct towards Miss Smith at the Crown Inn ball, where Mr. Knightley (a true knight in shining armour) came to her rescue and saved her from public humiliation. Mr. Elton’s reaction towards Miss Smith pointed out how much Emma misjudged Miss Smith’s tenuous connection to the gentry, for Mr. Elton thinks too highly of himself and his own social standing to ally himself to the bastard daughter of a gentleman.

Alaister Sooke makes the comment that for all its finery and sophistication the ball (it was decorous and tightly controlled) was also primeval, with the subconscious very much in play. The way the dancers were dressed, with women revealing lots of cleavage and the men revealing their groins in tight-fitting trousers, was totally sexual in nature.

The dancers get fitted for their breeches, which revealed quite a bit of the male anatomy, especially the groin area. Image @BBC2.

You are so right, Tony. Let’s take the case of menswear ca. 1813. Although the colors were muted, the silhoutte was quite athletic. The front of a man’s coat was cut high so that his body was fully revealed in front from the waist down. Men tucked their long shirt tails between their legs, which served as underwear. Because their calves were exposed, it was important for men to dance well, since all their steps were in full view. Women’s legs were hidden by their skirts and they could make a mistake or two without much notice. I was struck by how much the modern dancers enjoyed the evening and how much their costumes and the setting affected them.

The ladies in the series wore authentic underwear. Underneath the muslins and silks they wore undergarments consisting of a chemise and petticoat. There was actually a lot going on below the skirt, but the ladies generally went knickerless. Even when women wore underdrawers, the crotch area remained open and they remained so until the late 19th c. or early 20th century. Crotchless knickers were the norm! Image @BBC2

A courting couple made sure to reserve the supper dance for each other (or the dance just before the evening meal), for this meant that they could extend the time they spent together to include the meal, which was generally served at midnight. In the series, Ivan Day and his staff slaved to make the dishes, for they were served à la française (in the French style), or all at once. Preparing dishes for such a service required a great deal of skill and Herculean effort, for hot meals needed to be served hot, while delicate ices needed to remain frozen until they were consumed. At the dinner table in this special, a mild scene of chaos ensued, with servants bringing platters from one end of the table to the other, guests handing platters around, and others reaching across the table to sample a tidbit. Ragout of Veal, one of Jane Austen’s favorite dishes, was served. This dish was frequently mentioned by her, particularly in Pride and Prejudice. As an aside, one could readily discern at the supper ball which guests had manners and those who did not.

The ragout of veal at the supper dance was associated with high living. Image @BBC2

More on the topic:

Read Full Post »