Inquiring readers,

Inquiring readers,

My apologies to author Jessica Volz–who contacted me weeks before the COVID-19 lockdown about her book–for posting my review of her book several months late. She has been so patient that I must thank her for her graciousness. – Vic Sanborn

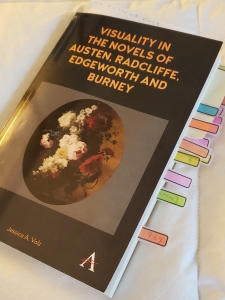

The highly interesting and informative Visuality in the Novels of Austen, Radcliffe, Edgeworth and Burney, is no fast walk in the park as far as reading goes, but it is worth the effort since it is filled with new and insightful information. One cannot skip or skim to learn about the way Austen and female writers of her era used visuality in language to communicate hidden meaning. In order to understand how visual language transmitted women’s emotions, issues, and areas of concern in a patriarchal society, I digested Dr. Volz’s words and reflected on how her observations helped me to reassess my understanding of the hidden language these 18th and 19th century authors used.

In her book, Dr. Volz studied the novels of four authors published between 1778 and 1815. Three of those novelists, Radcliffe, Edgeworth, and Burney, enjoyed recognition during Austen’s life, while Austen ultimately found lasting fame as a literary giant. This was a time when women’s views on their rights shifted, greatly helped by the Enlightenment’s campaign for human rights, the influence of the French Revolution in questioning conventional perceptions of women, and Mary Wollstonecraft’s revolutionary writings. Wollstonecraft wanted male-dominated females to attain power over themselves. While this emancipation would take a longer time than she even envisioned, Wolstonecraft influenced contemporary women authors to employ an approach that “concealed their resistance within an artful narration.” (1. Volz, p. 210.)

Volz’s findings found that in a patriarchal society, when women were expected to behave modestly and correctly and use phrases that were acceptable to their male relatives and husbands, female authors found a linguistic end-around through visual references. They:

…focused on ways their texts reveal the authors’ approaches to issues explored or suggested in the novels, including “women’s difficulties, polite society’s anxieties and the problems inherent in judging by appearances.” – (2. Painting With Words, Claire Denelle Cowart, JASNA, 2019.)

Thus, while the novels written by these four authors seemed to outwardly conform to societal standards, their heroines thought for themselves.

While the forms and functions of visuality that women novelists employed to their rhetorical advantage vary, they channeled their thoughts through several distinct visual pathways: visible and ‘invisible’ likenesses, architectural metaphors, the ‘made-up’ social self and communicating countenances.” (Volz, p. 212)

This review discusses some ways in which Dr. Volz examines how Austen employed the forms and functions of visuality. When she sent me her book, she was correct in predicting that I would be the most affected by the chapter that discussed Jane Austen. I’ll start with my first (and still favorite) Austen novel, Pride and Prejudice, and heroine, Elizabeth Bennet.

Elizabeth Bennet, Pemberley, and Mr. Darcy

While Dr. Volz discusses Pemberley well into Chapter 1, I did not begin to truly understand her analysis of Austen’s visuality until I reached this section. I knew Elizabeth Bennet was my favorite fictional heroine from almost the moment I met her at the age of fourteen. Lady Catherine deBourgh expressed the 18th century attitude towards women when she accused Elizabeth of being obstinate and headstrong. In other words, she was not the right sort of lady, especially not for Mr. Darcy.

On that first reading, I instantly understood that Elizabeth’s feelings towards Mr. Darcy were transformed as she walked along the beautiful grounds of Pemberley, viewed the house from afar in its perfect setting, moved throug its exquisite interior, listened to the raptures of his housekeeper as she described her master’s kindnesses, compared a miniature of his youthful self to Mr. Wickham’s (whose actions, as related by the housekeeper, described a cad), and then finally studied a large painted portrait of Mr. Darcy that to Elizabeth seemed true to life and captured her new understanding of his essence.

The architectural metaphors that Volz mentioned explain much in this description of Elizabeth’s leisurely ramble with the Gardiners along Pemberley’s grounds:

They gradually ascended for half a mile, and then found themselves at the top of a considerable eminence, where the wood ceased, and the eye was instantly caught by Pemberley House, situated on the opposite side of a valley, into which the road with some abruptness wound. It was a large, handsome, stone building, standing well on rising ground, and backed by a ridge of high woody hills;—and in front, a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance. Its banks were neither formal, nor falsely adorned. Elizabeth was delighted. She had never seen a place where nature had done more, or where natural beauty had been so little counteracted by an awkward taste. They were all of them warm in her admiration; and at that moment she felt that to be mistress of Pemberley might be something!” (Pride and Prejudice)

As she views Pemberley’s grounds, Elizabeth can see herself living in this natural setting as its mistress, but she realizes with some sadness that this is no longer possible. To her regret, she rejected Mr. Darcy’s proposal based on her first impressions. Now that she sees him through a new lens, she recognizes how much their tastes and inclinations have in common. Moreover, she understands that Darcy, like his estate, Pemberley, has no artifice.

The lack of artifice is also how Mr. Darcy views Elizabeth – early in their association, he admires her expressive eyes and the liveliness of her character, which gave her a natural beauty much like the estate grounds he loves.

But no sooner had he made it clear to himself and his friends that she had hardly a good feature in her face, than he began to find it was rendered uncommonly intelligent by the beautiful expression of her dark eyes.” (Pride and Prejudice)

Austen also emphasized Darcy’s admiration of Elizabeth’s unorthodox, unladylike walk to Netherfield, which “improved her figure’s picturesque quality and intensified the expressiveness of her eyes.” (Volz, p. 60). His appreciation echoes the ideal of the picturesque in writings by Johann Kaspar Lavater (a Swiss physiognomist, philosopher, and theologian) and William Gilpin in his Observations Relating Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty (1786) which appreciated the irregular features of a person, place, or setting and that “gave them a certain charm and made them desirable subjects for painting.” (Ibid)

Image, Wikimedia Commons

Volz writes much more about the mastery in which Austen unites Elizabeth and Darcy through visible and invisible likenesses and architectural metaphors. Yet Austen is known for her austere descriptions of person, place or thing. How does this reconcile with visuality? One of the best-known images of Austen is a silhouette used by Jane Austen societies the world over. Early in her book, Volz mentions Austen’s affinity and familiarity with silhouettes. Like her contemporary profilists, “Austen sought to produce verbal ‘shades’ that ‘”convey the most forcible expression of character.”’ (3. Marsh & Hickman, Shades from Jane Austen.)

Austen’s habit of eschewing detail when describing characters’ appearance indicates her preference for using a single telling line that, like the silhouette, supplies ‘infinite expression’ though a profile that is not overshadowed by the particulars within it.” (Volz, p. 36)

For me, this explains Austen’s spare use of details and how this writing style encourage the readers’ imaginations to take hold. As I age, I find new depths in her plots, whose meanings change as my perceptions of the world (and knowledge of her era) change. For example, as a young girl/woman, I couldn’t stand or understand Mrs. Bennet, and found her an irritating though comic character. The more I studied Austen’s era and the circumscribed lives women were forced to live, my sympathy for Mrs. Benne’s poor nerves and her quest to find husbands for her five daughters increased, while my patience with Mr. Bennet (though I never stopped appreciating his wit) waned.

Volz writes that “Austen’s use of an aesthetic vocabulary of character in her fiction directs the reader’s attention to the act of viewing and its ultimate subjectivity in creating couples united in their affections.” So true, but Austen does this so economically and so masterfully, that I am constantly astounded and motivated to reread her novels.

Elinor Dashwood and Lucy Steele

In Sense and Sensibility, Volz traces the evolution of Elinor’s certainty that Edward Ferrars favors her against her painful, but inexorable understanding that he is engaged to Lucy. The proof is supplied through physiognomic means in the form of a miniature likeness of Edward that he gave to his intended. Does this miniature prove that he loves her? Elinor isn’t sure. While devastated, she is a skillful observer, as painters often are. Why do he and Lucy only see each other twice a year? And why, she wonders, did Lucy never give him her picture?

This plot in Sense and Sensibility reads like a mystery, with Austen using visuality clues to lead Elinor/us to the realization that, by not giving Edward her visual likeness, Lucy’s attachment is tenuous at best. In Lavater’s opinion, a portrait is “more expressive than nature.” One can then deduce that a ring with a lock of Lucy’s hair means little compared to an actual likeness. Elinor can discern no real affection in Lucy’s body language or demeanor towards Edward, but this knowledge gives her no comfort. Only a woman is allowed to end an engagement and Edward is too honorable to go against convention. At the end of the novel, Elinor’s intuition proves to be correct and Edward, unceremoniously dumped by Lucy in favor of his brother, is free to declare himself to the woman he loves.

Emma Woodhouse and Harriet Smith

When it comes to the heroine that no one but Austen will much like, Volz explains that Emma is “as much of a product of Highbury as she is a shaper of it.” (Volz, p. 79). Emma’s status, while high in the ranks of Highbury society, does not detract from the dullness of her daily life as a modest female. In her twenty-one years, she hasn’t visited London, a mere few hours drive away in a carriage, or a seaside resort, or even Box Hill (until the famous scene at the end of the novel). After Miss Taylor became Mrs. Weston, a bored Emma (who took credit for uniting Mr. Weston with her governess) looks for another “project.” When her thoughts turn to Harriet Smith, her imagination and manipulation take over. She will mold Harriet into her vision of a young lady with prospects, even though Harriet is the natural daughter of an unknown somebody.

A famous scene in the novel centers on Emma painting a portrait of Harriet. Volz describes this portrait as an example of the heroine’s self-delusions (the likeness depicts Harriet as Emma would like her to be), and that the friendship among the two women represents something other than themselves. “Emma has redrawn Harriet’s character, which now ‘acts’ as improperly as the eye and hand that have shaped it.” (Volz, p. 80) Needless to say, Emma’s portrayal of Harriet has more to say about the painter than the sitter.

From the start of the alliance, the reader understands that this friendship is woefully out of balance. A weak mouse stands little chance against a powerful cat, and so Emma’s machinations blindly continue, but after Harriet reveals her love for Mr. Knightley, which she (unbelievably) thinks is reciprocated, Emma finally sees ‘the blinders of her own head and heart,’ although Emma feels sorrier for herself in her self-deception than she feels for her deluded friend. “Austen’s visual technique stages for the reader the dramatic shift in the heroine’s vision and perceptions.” (Ibid.) This is true, but Austen’s young heroine still has much to learn before the story ends.

In this section, Volz provides more interesting observations about the Emma/Mr. Knightley relationship, which readers will find equally fascinating.

Fanny Price and Mansfield Park

My final thoughts about Volz’s book are about her analysis of Fanny Price. Fanny’s journey as a young girl transported to a strange new house is demonstrated by the rooms she lives in. At first the lonely child cries herself to sleep, but as the novel progresses, the rooms she occupies within the house, first as an outsider and then as an accepted member of the household, correspond with her emotional growth. The more comfortable Fanny feels in her adopted home, the more she blossoms. Fanny’s “acquisition of a new private space within Mansfield serves as a metaphor for her progress towards social acceptance.” (Volz, p. 76)

When Fanny is banished to live with her parents in Portsmouth, she learns how much she has changed and grown. “Aesthetic contrasts teach the heroine and the reader to see that Mansfield’s values are diametrically opposed to those at Portsmouth, with its crowded, agitating interior.” (Ibid.) Mansfield Park has become Fanny’s home, and within it she shines both outwardly and inwardly.

Austen’s evolving views towards ideal landscapes are personified in her descriptions of Pemberley and Mansfield Park:

Whereas Elizabeth’s raptures over Pemberley’s physiognomic display highlight the place’s picturesque irregularity, here [in Mansfield Park], Austen defers to the presentation of organized beauty and agreeable symmetry, implying her own changed view of landscape design.” (Volz, p. 77)

Water at Wentworth, Humphry Repton. The second image shows the improvements to the scene

This is not surprising, since one of the premier landscape architects at the time that Austen wrote Mansfield Park was Humphry Repton, whose work Jane prominently mentions in the novel. Repton’s habit of removing irregularities from a landscape can be viewed in his red books, in which he presented before and after watercolors of his designs to his clients. The “after” watercolors remove any impediments to a perfect view or irregularities (by cutting down trees or adding features, such as a pond or a Palladian bridge).

I should also mention that Volz’s thorough examination of Austen’s visual aesthetic includes the author’s use of free indirect discourse (FID), which characterizes Austen’s writing. Approximately 20-30% of Austen’s narration is FID, in which both the narrator and a character are speaking at once.

Outside of direct dialogue, free indirect discourse is the most common, economical, and sophisticated way novels relay information about thoughts and speech. […] Austen’s employment of FID was revolutionary, for while earlier authors had used it to some degree, it remained to Austen to take advantage of the wide range of how FID could be deployed to manipulate our ironic understanding of her characters.” (4. Mooneyham White, Discerning Voice Through Austen, JASNA)

In our day and age, many readers no longer recognize the subtleties that 18th/19th century readers understood when reading novels by contemporary female authors. Dr. Volz’s observations help us to analyze their subtext and, in my case, prompted me to rethink my earlier reactions to Austen’s characters.

One can use Dr. Volz’s observations in analyzing other Austen characters on our own – Anne Elliot, Admiral and Mrs. Croft, and Henry Tilney, to mention a few. Austen scholars and Austen fans who have delved deeply into her characters’ lives and the history of Regency England will find this book fascinating and a useful reference in their libraries.

Image of Dr. Volz from Nineteenth-Century Studies Association

About Dr. Jessica A. Volz:

Dr. Jessica A. Volz of Denver, Colorado is an independent British literature scholar and international communications strategist whose research focuses on the forms and functions of visuality in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century women’s novels. Her latest book, Visuality in the Novels of Austen, Radcliffe, Edgeworth and Burney (London and New York: Anthem Press, March 2017), discusses how visuality — the continuum linking visual and verbal communication — provided women writers with a methodology capable of circumventing the cultural strictures on female expression in a way that concealed resistance within the limits of language. The title offers new insights into verbal economy and the gender politics of the era spanning the Anglo-French War and the Battle of Waterloo by reassessing expression and perception from a uniquely telling point of view.

Dr. Volz holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of St. Andrews and a B.A./M.A. in European Cultural Studies and Journalism from Boston University. She was recently named an ambassador of the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation, which was created to harness the global passion for Jane Austen to fund literacy resources for communities in need across the world. Dr. Volz has also served as the editor of two Colorado legal publications and as a translator for a number of Paris-based companies. In her spare time, she enjoys planning tea parties and plotting novels.

References:

1. Volz, Jessica A. Visuality in the Novels of Austen, Radcliffe, Edgeworth and Burney. Anthem Press, Anthem Nineteenth-Century Series, 2020. Print. ISBN:13-978-1-78527-253-0 (pbk).

2. “Painting with Words,” Visuality in the Novels of Austen, Radcliffe, Edgeworth and Burney, Jessica A. Volz. Review by Claire Denelle Cowart, JASNA News, 2019. PDF document downloaded May 18, 2020: file:///C:/Users/18046/Downloads/JASNANews_Summer2019_BookReviews.pdf

3. Hickman, Peggy and Marsh, Honoria, Shades from Jane Austen, London: Parry, Jackman 1975, xv-xxii.

4. Mooneyham White, Laura, Discerning Voice through Austen Said: Free Indirect Discourse, Coding, and Interpretive (Un)Certainty, Jane Austen Society of North America, Volu. 37, No1—Winter 2016, Downloaded May 20, 2020: http://jasna.org/publications/persuasions-online/vol37no1/white-smith/

Additional:

Coffee, Tea and Visuality: The Art of Attraction in ’‘Pride and Prejudice’, Jessica A.Volz, Jane Austen Literacy Foundation, February 22, 2017, Downloaded May 18, 2020:https://janeaustenlf.org/pride-and-possibilities-articles/2017/2/21/issue-8-coffee-tea-and-visuality

Edmundson, Melissa, “A Space for for Fanny: The Significance of Her Rooms in Mansfield Park,” Persuasions On=Line, Jane Austen Society of North America, V. 23, No.1 (Winter 2002), Downloaded 5/20/2020: http://www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol23no1/edmundson.html

Lavater, Johann Casper. Essays on Physiognomy: For the Promotion of the Knowledge and the Love of Mankind. Illustrated by more than eight hundred engravings accurately copied; and some duplicates added from originals. Executed by or under the inspection of, Thomas Holloway. Translated from the French by Thomas Holdcroft. 3 vols. 5 bks. London: John Murray 1789-98.

Oesteich, Kate Faber, “Jessica A. Volz – Interview,” Nineteenth-Century Studies Association (NCSA), May 10, 2017. Downloaded May 18, 2020: https://ncsaweb.net/2017/05/10/jessica-a-volz/

Purchase the book:

- Barnes & Noble: Nook Book $17.49

- Anthem Press: Anthem Nineteenth-Century Series, Paperback $40.00

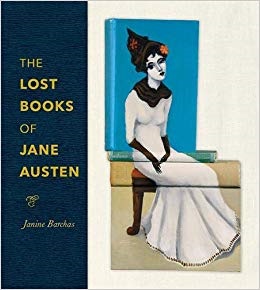

The Lost Books of Jane Austen by Janine Barchas is a beautiful book – a bound hardcopy with almost one hundred color photographs of affordable, mass-produced novels that, outside of expensive hand pressed editions, contributed to Jane Austen’s ever-increasing fame. The detective work and scholarship that Dr. Barchas embarked on for a decade to find hundreds of inexpensive, disposable Jane Austen books to study their role in Austen’s rapidly growing popularity is awe inspiring.

The Lost Books of Jane Austen by Janine Barchas is a beautiful book – a bound hardcopy with almost one hundred color photographs of affordable, mass-produced novels that, outside of expensive hand pressed editions, contributed to Jane Austen’s ever-increasing fame. The detective work and scholarship that Dr. Barchas embarked on for a decade to find hundreds of inexpensive, disposable Jane Austen books to study their role in Austen’s rapidly growing popularity is awe inspiring.

Author Bio:

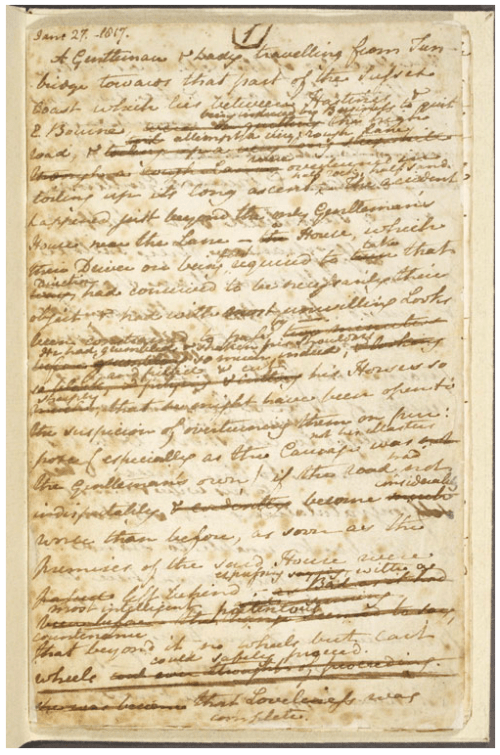

Author Bio: As almost all Jane Austen enthusiasts know, her unfinished novel, Sanditon, has been adapted for a limited television series by Andrew Davies. It aired on ITV in Great Britain in the fall and will be shown on PBS Masterpiece Classics starting January 12, 2020. It seems that after the first episode, Mr. Davies deviated from the complex world Jane Austen created to insert his male sensibilities into the plot, but I am getting ahead of myself. (More to come in January.) The intent of this review is a plea for Jane Austen fans to read Sanditon before watching the PBS series. You will be doing yourself a favor.

As almost all Jane Austen enthusiasts know, her unfinished novel, Sanditon, has been adapted for a limited television series by Andrew Davies. It aired on ITV in Great Britain in the fall and will be shown on PBS Masterpiece Classics starting January 12, 2020. It seems that after the first episode, Mr. Davies deviated from the complex world Jane Austen created to insert his male sensibilities into the plot, but I am getting ahead of myself. (More to come in January.) The intent of this review is a plea for Jane Austen fans to read Sanditon before watching the PBS series. You will be doing yourself a favor.