A guest post by Katherine Cowley

The Author

Readers and scholars have generally seen the reaction to snow in Emma as an overreaction, both ridiculous and absurd. Yet a look at the snowfalls in England in January and February of 1814 puts the snow in Emma—which was published in December of 1815—in context. Readers of the time would have seen the fears of snow as justified, or, at the very least, understandable.

A pivotal scene in Emma occurs at a Christmas Eve dinner at the Westons’ home. The dinner brings together a number of important characters—Emma, her father Mr. Woodhouse, the Westons, Mr. Knightley, Mr. Elton (who Emma believes is in love with her friend Harriet), and Isabella and John Knightley (Emma’s sister and brother-in-law). Yet the perfect holiday meal does not occur—the falling snow causes a panic (especially for Mr. Woodhouse), and everyone leaves early, hurrying home before more snow can arrive. This places Emma in the uncomfortable position of being alone in a carriage with Mr. Elton, which leads to one of literature’s most famous drunk proposals.

The General Consensus: Absurd Reactions to Snow

Modern readers and film viewers love to laugh at the absurd reactions to snow in Emma. We know with absolute certainty that it does not snow very much in England and that the reactions of the characters are overblown.

Take, for example, a sampling of quotes on the scene from past issues of Persuasions: The Jane Austen Journal. Louise Flavin calls Mr. Woodhouse an “over-cautious valetudinarian worrying over a half-inch snowfall.” Sara Wingard writes of the “false alarms raised.” Juliet McMaster describes how Mr. Woodhouse “becomes almost catatonic.” Jan Fergus features the scene in an article titled “Male Whiners in Austen’s Novels.”

In Nora Bartlett’s book, Jane Austen: Reflections of a Reader, she includes a chapter titled “Emma in the Snow.” She writes:

I have always treasured the snowfall in Chapter 15 of Emma, which endangers no one’s safety, despite Mr. Woodhouse’s fears, but threatens everyone’s equanimity: at the news that snow has fallen while the party from Hartfield is having an unwonted evening out at Randalls, “everybody had something to say”—most of it absurd.

Not Just Mr. Woodhouse

Mr. Woodhouse is often seen as a hypochondriac, and the portrait of him which Austen paints throughout the novel invites us to question his sense and find him amusing. When he learns of the snow, we read that he is “silent from consternation.” When he does speak, he says, “What is to be done, my dear Emma?—what is to be done?” Yet he is not the only character who reacts to the snow as if it is a serious matter.

Many readers have pointed out that the most sensible people during the evening are Emma and Mr. Knightley. Yet earlier in the day, Emma herself anticipates that snow could be a problem:

It is so cold, so very cold—and looks and feels so very much like snow, that if it were to any other place or with any other party, I should really try not to go out to-day—and dissuade my father from venturing; but as he has made up his mind, and does not seem to feel the cold himself, I do not like to interfere, as I know it would be so great a disappointment to Mr. and Mrs. Weston.”

During the snow scene, Mr. Knightley behaves rationally—he steps away from the house and checks on the road, discovering that there is only a half inch of snow. He also converses with the coachmen, who “both agreed with him in there being nothing to apprehend.” Taking this effort indicates his desire to help Mr. Woodhouse feel comfortable—but it also indicates that he considers it worth checking on the quantity of snow.

Mr. Weston, on the other hand, begins joking about wanting everyone to be trapped in his house:

[He] wished the road might be impassable, that he might be able to keep them all at Randalls; and with the utmost good-will was sure that accommodation might be found for every body, calling on his wife to agree with him, that with a little contrivance, every body might be lodged, which she hardly knew how to do, from the consciousness of there being but two spare rooms in the house.

Meanwhile, Mr. John Knightley speaks of what he perceives as the worst harm that could come to them:

I dare say we shall get home very well. Another hour or two’s snow can hardly make the road impassable; and we are two carriages; if one is blown over in the bleak part of the common field there will be the other at hand. I dare say we shall be all safe at Hartfield before midnight.”

It is little wonder that Norah Bartlett concludes that “‘everybody had something to say’—most of it absurd.” There is a beautiful absurdity to the scene, a lovely snapshot of humanity as we see individuals react very differently to a single threat.

Yet while Austen may be intentionally creating a situation meant to be read as absurd, the threat of snow would have felt real to readers of Emma in 1815.

The Snows of Early 1814

The novel Emma was published in December of 1815. Contemporary readers would have recent memories of frightening winters due to the intense snow falls across England during January and February of 1814.

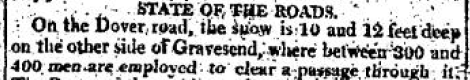

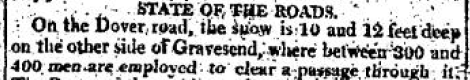

Let’s take, as an example, the reports of snow on January 24th, 1814. In The Times, which was published in London, there was an article titled the “State of the Roads.”

Transcription: State of the Roads. On the Dover road, the snow is 10 and 12 feet deep on the other side of Gravesend, where between 300 and 400 men are employed to clear a passage through it.

Clearly, it is no small matter for the road from London to Dover to be covered with 10 to 12 feet of snow, if more than 300 men were hired to shovel it. Yet it was not just the area southeast of London that was covered by snow. In Exeter—in southwest England—there was 4 to 6 feet of snow. Carriages heading from Bath to Marlborough became stuck in the snow. In Worcester and Gloucester it was reported that “it was as easy to get through a wall as pass the drifts of snow.” Mail coaches from Liverpool and Manchester made it to London, but they “risked their lives” in the process. Huge amounts of snow were also reported in Glasgow and Edinburgh, Scotland.

The article continues:

Transcription: Never since the establishment of mail coaches has correspondence met with such general interruption as at present. Internal communication must, of course, remain at a stand till the roads are in some degree cleared; for besides the drifts by which they are rendered impassable, the whole face of the country presenting one uniform sheet of snow, no trace of road is discoverable, and travellers have had to make their path at the risk of being every moment overwhelmed. Waggons, carts, coaches, and vehicles of all descriptions are left in the midst of the storm. The drivers finding they could proceed no further, have taken the horses to the first convenient place, and are waiting until a passage is cut, to enable them to proceed with safety.

We can hardly blame Mr. John Knightley for his speculations about losing a carriage in the snow, when so many travelers in 1814 were forced to abandon their carriages.

On January 25, 1814, The St. James’s Chronicle discussed the potential sewage problems that could overwhelm (or flood) London, should the snow melt quickly. The paper also reported that in the village of Dunchurch, “drifts have exceeded the height of 24 feet.”

This was not snow to laugh at—for weeks the snow built up, making travel near impossible. In London, the Guildhall issued announcements not to shovel the snow from roofs onto the roads, because of the trouble it was causing. The snow did begin to melt, but then it became even colder, so cold in fact that the Thames River froze over in London, and the last London Frost Fair was held on its frozen waters. Printing presses were pulled onto the ice, meat was roasted on fires on the surface of the river, and tents were erected with various attractions. The ice was thick enough that an elephant—yes, an elephant—walked across the river, from one side of the Thames to the other.

The Fair on the Thames, Feb. 1814, by Luke Clenell (art in public domain). (To read more about the frost fair, see the following sources at the bottom of this post: Andrews; de Castella; Frost Fairs; Frostiana; and Knowles.)

The snows in 1814 were not just inconvenient: they were dangerous and sometimes even deadly.

During the Regency period, it was difficult to stay dry and warm. Two previous posts on Jane Austen’s World address the efforts people took to keep warm in the Regency: part 1 and part 2.

In another article in The St. James’s Chronicle from January 25, 1814, several snow-related injuries were described. First we read that a middle-aged man slipped and fractured his knee, and then we read:

A young Lady of Kentish-town, whose name is Eustace, by passing from thence on Friday to London, by the public foot-path behind the Veterinary College, got completely immersed in a deep ravine by the side of the path which she was attempting to cross. After struggling for some time, she became quite exhausted, and must have fallen a victim to her unfortunate situation, had not two Gentlemen, who witnessed her distress, although at a considerable distance, ventured to her assistance, and relieved her from her perilous situation.”

With vivid prose, the article paints the precarious situation for Eustace—she almost fell “a victim to her unfortunate situation,” or, in other words, she almost froze to death.

While the middle-aged man and Eustace recovered from their mishaps, others were not so fortunate.

This article, from the 19 January 1814 edition of The Times, reprinted information about deaths in Exeter and Shrewsbury on the 15th of January:

Transcription: Several accidents have occurred, some of which were fatal; on Wednesday a soldier was found dead on Haldon…and yesterday three of the Renfrew Militia were dug out near the same spot, and their bodies conveyed to Chudleigh…. Last week, several of the West Middlesex Militia, who had volunteered for foreign service, were frozen to death on their march from Nottingham. The unfortunate men had been drinking till they were intoxicated, and, lying by the road side, slept—never to wake again!

A week later, on the 26th of January, The Times reported on three more people who died in the snow.

Transcription: The Guard of the Glocester mail reports, that three persons now lie dead at Burford; one a post-boy, who was dug out of the snow yesterday morning; a farmer, who was frozen to death on horseback; and another person, who died in consequence of the inclemency of the weather.

Reports of deaths caused by snow, ice, and cold were printed regularly in newspapers across the country throughout January and February of 1814.

Readers of Emma would have read of death after death in the snow. Some of the readers might have become trapped in carriages in the snow, or forced to lodge with an acquaintance during the storm. If they had not personally suffered from the weather, they would have known people who had suffered. Would these readers really have blamed Mr. Woodhouse for asking “What is to be done, my dear Emma?—what is to be done?”

We do not have any letters from Jane Austen written in January or February of 1814, so we cannot directly access her thoughts on these snowfalls, yet we do know that she began writing Emma in January of 1814. She would have been well aware of the public memory that would develop around these snowfalls, and she uses the snow to not only influence the plot of Emma, but to create larger symbolism.

The scholar Elizabeth Toohey makes the argument that Mr. Knightley’s proposal to Emma is superior to Mr. Elton’s, in part because of the snow and all it symbolizes:

“Mr. Elton’s proposal takes place in a closed carriage in a snowfall at night with all the associations of coldness, darkness, and enclosure, in contrast to Mr. Knightley’s proposal, which occurs in the garden in the warmth of a late summer evening.”

Much of the beauty of Mr. Knightley’s proposal derives from its contrast with Mr. Elton’s proposal on a snowy night.

The characters of Emma lived in an age without snow plows, snow tires, or central heating, when large snowfalls were not just an inconvenience. Snow regularly caused disruption, injury, and death.

During their journey to the Westons, as the first snowflakes begin to fall, John Knightley declares:

“The folly of not allowing people to be comfortable at home—and the folly of people’s not staying comfortably at home when they can! If we were obliged to go out such an evening as this, by any call of duty or business, what a hardship we should deem it;—and here are we, probably with rather thinner clothing than usual, setting forward voluntarily, without excuse, in defiance of the voice of nature, which tells man, in every thing given to his view or his feelings, to stay at home himself, and keep all under shelter that he can.”

John Knightley’s view of snow has a certain soundness to it. Wouldn’t it behoove us all to take what shelter we can during difficult times?

As we read the snow scene in Emma, let us do so with a realization that while Austen may be painting an absurd portrait, the views of these characters are not, in and of themselves, absurd. For 1815 readers, a fear of snow and ice would be justifiable, or at the very least, understandable.

_________________________________________________________________

About the author

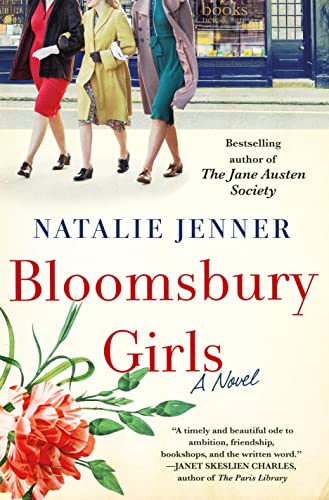

Katherine Cowley is the author of the Mary Bennet spy novel, The True Confessions of a London Spy, which features Mary Bennet of Pride and Prejudice in London during January and February of 1814. In addition to surviving epic amounts of snow and attending the last Ice Fair ever held on the Thames, Mary experiences her first London Season and investigates the murder of a messenger for Parliament.

Note from Vic, Jane Austen’s World: In 2021, we reviewed Katherine Cowley’s first mystery in the Mary Bennet series, The Secret Life of Mary Bennet. Attached to it is an interview with the author.

Accessing Regency Newspapers

If you would like to explore Regency newspapers, you can purchase an affordable monthly subscription to the British Newspaper Archive. They have digitized hundreds of newspapers from across the United Kingdom. While to my knowledge individual subscriptions to The Times Digital Archive are not available, many libraries and university libraries have subscriptions that allow you to browse and search the archives of The Times.

References and Further Reading

Andrews, Willam. Famous Frosts and Frost Fairs in Great Britain, George Redway, 1887. Accessed through Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/55375/55375-h/55375-h.htm, 1 Jan 2022.

Bartlett, Nora. Jane Austen: Reflections of a Reader, edited by Jane Stabler, Open Book Publishers, 2021.

de Castella, Tom. “Frost fair: When an elephant walked on the frozen River Thames.” BBC News Magazine, 28 Jan. 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-25862141. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022.

Fergus, Jan. “Male Whiners in Austen’s Novels.” Persuasions: The Jane Austen Journal, vol. 18, 1996, pp. 98-108.

Flavin, Louise. “Free Indirect Discourse and the Clever Heroine of Emma.” Persuasions: The Jane Austen Journal, vol. 13, 1991, pp. 50-57.

“Frost Fairs: Where Thames Smooth Waters Glide. Frost Fairs on the River Thames.” Thames.me.uk, https://thames.me.uk/index.htm. Accessed 31 January 2022.

Frostiana: or a History of The River Thames, In a Frozen State, G. Davis, 1814.

“Keeping Warm in the Regency Era, Part One.” Jane Austen’s World, 21 Jan. 2009, https://janeaustensworld.com/2009/01/21/keeping-warm-in-the-regency-era-part-one/. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022.

“Keeping Warm in the Regency Era, Part Two.” Jane Austen’s World, 3 Feb. 2009, https://janeaustensworld.com/2009/02/03/ways-to-keep-warm-n-the-regency-era-part-2/. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022.

Knowles, Rachel. “The Frost Fair of 1814.” Regency History, 3 Jan. 2021, https://www.regencyhistory.net/2020/05/the-frost-fair-of-1814.html. Accessed 31 Jan. 2022.

McMaster, Juliet. “The Secret Languages of Emma.” Persuasions: The Jane Austen Journal, vol. 13, 1991, pp. 119-131.

Mullan, John. “How Jane Austen’s Emma changed the face of fiction.” The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/dec/05/jane-austen-emma-changed-face-fiction. Accessed 31 January 2022.

The St. James’s Chronicle (London, England), Tuesday, Jan. 25, 1814; pp. 1-4; Issue 8757. Accessed through The British Newspaper Archive 28 Jul. 2020.

The Times (London, England), Monday, Jan. 19, 1814; pp. 1-4; Issue 9122. Accessed through The Times Digital Archive 31 Jan. 2022.

The Times (London, England), Monday, Jan. 24, 1814; pp. 1-4; Issue 9126. Accessed through The Times Digital Archive 27 Jul. 2020.

The Times (London, England), Monday, Jan. 26, 1814; pp. 1-4; Issue 9128. Accessed through The Times Digital Archive 31 Jan. 2022.

Wingard, Sara. “Folks That Go a Pleasuring.” Persuasions: The Jane Austen Journal, vol. 14, 1992, pp. 122-131.

Read Full Post »

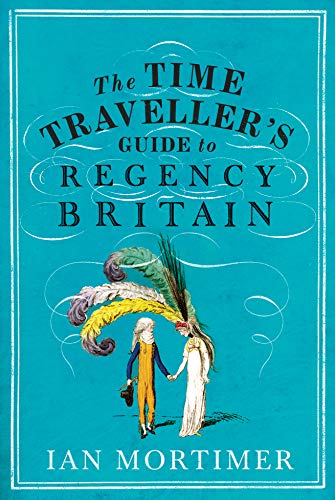

Strictly speaking the oficial Regency lasted from 1811 to 1820, but the author, Ian Mortimer, takes the reader on a journey to Great Britain – England, Wales and Scotland – from 1789 to 1830, a time period that is in line with most other historians, literary critics and antiques experts.

Strictly speaking the oficial Regency lasted from 1811 to 1820, but the author, Ian Mortimer, takes the reader on a journey to Great Britain – England, Wales and Scotland – from 1789 to 1830, a time period that is in line with most other historians, literary critics and antiques experts.

After reading this book, I had a comprehensive overview of the Regency era and recommend it to anyone interested in this period. Amazon Kindle edition (See cover to the right) offers a sample of the book’s Introduction, and Chapters 1 & 2 in full.

After reading this book, I had a comprehensive overview of the Regency era and recommend it to anyone interested in this period. Amazon Kindle edition (See cover to the right) offers a sample of the book’s Introduction, and Chapters 1 & 2 in full. Dr Ian Mortimer has been described by The Times newspaper as ‘the most remarkable medieval historian of our time’. He is best known as the author of The Time Traveller’s Guides: to Medieval England (2008); to Elizabethan England (2012); to Restoration Britain (2017); and to Regency Britain (2020). He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, and has published research in academic journals touching on every century from the twelfth to the twentieth. For more information, see

Dr Ian Mortimer has been described by The Times newspaper as ‘the most remarkable medieval historian of our time’. He is best known as the author of The Time Traveller’s Guides: to Medieval England (2008); to Elizabethan England (2012); to Restoration Britain (2017); and to Regency Britain (2020). He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, and has published research in academic journals touching on every century from the twelfth to the twentieth. For more information, see