“I wish you a cheerful and at times even a Merry Christmas.” — Jane Austen

While Christmas festivities were not as commercial as they were during Queen Victoria’s and our time, families in Jane Austen’s era celebrated the holiday with much merriment, many gatherings and parties, and some gift giving. Houses were decorated with evergreens and kissing boughs made of holly, ivy, and mistletoe, although these greens were not brought in until Christmas Eve. On the same night, a large yule log was ceremoniously brought into the house, with the hope that it would last for the rest of the holiday season.

Celebrations lasted from December 6th, St. Nicholas Day, when presents were given, to January 6th , Twelfth Night. On December 25th people attended church service, then ate Christmas dinner. December 26th was known as Boxing Day, when staff and servants were given Christmas boxes and that day off by their benefactors.

The season ended the night of January 5th , the last day of Christmastide, with a Twelfth Night party filled with games and more partying. The revelers ate traditional foods, such as a slice of the elaborately decorated Twelfth Cake, that was topped with enough sugar, sugar figures, and sugar piping to cause a diabetic coma in a horse. (I might have exaggerated slightly.) After the revelers finished partying, superstition dictated that all decorations in the house be taken down and burned, else bad luck would befall the household for the year.

Certain foods marked the season.

“Just at this time these shops are filled with large plum-cakes, which are crusted over with sugar, and ornamented in every possible way. These are for the festival of the kings, it being part of an Englishman’s religion to eat plum-cake on this day, and to have pies at Christmas made of meat and plums.” – p. 63, Mr. Rowlandson’s England, text written by English poet Robert Southey as a fictitious Spanish tourist visiting England.

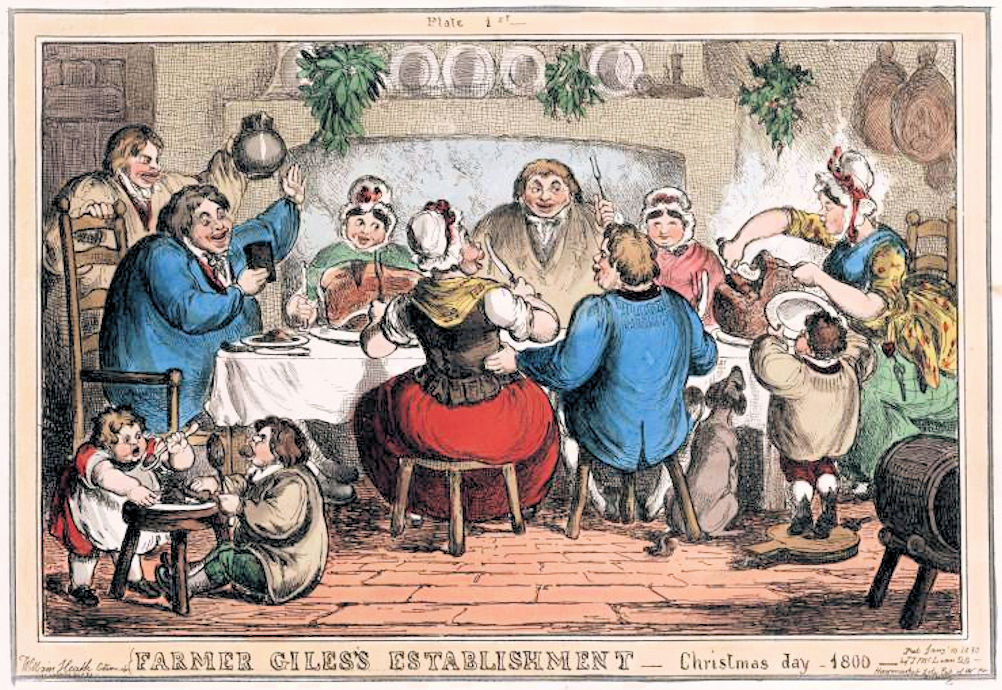

Farmer Giles’s Establishment: Christmas Day-1800. Science Museum Group Collection

In “A Miscellany of Christmas Pies, Puddings and Cakes,” Joanne Major describes the typical foods that were served: Christmas pudding, which started out as plum porridge or pottage (and is also known as plum or figgy pudding); sweet and savory mince pies; Christmas cake; and a savory Yorkshire Christmas-Pie. She includes the following quote in her article:

Stamford Mercury, 15th January 1808

At Earl Grosvenor’s second dinner at Chester, as Mayor of that city, on Friday the 1st instant there was a large Christmas pie, which contained three geese, three turkies, seven hares, twelve partridges, a ham, and a leg of veal: the whole, when baked, weighed 154 lbs.!

The following description confirms Robert Southey’s observation that there was no food or protein an Englishman wouldn’t eat, including animals and seafood from all parts of the world—turtles from the West Indies, curry powder from India, hams from Portugal, reindeer’s tongues from Lapland, caviar from Russia; sausages, maccaroni, and oil from Italy, which also provided olives along with France and Spain; cheeses from Switzerland; fish from Scotland; mutton from Wales; and game from France, Norway, or Russia (p 60, Mr. Rowlandson’s England). In his observations, Southey remarked that an Englishman would hunt and shoot anything that could be stuck in a pot.

Gout, a prevalent disease of the well-to-do Georgian, was the painful result of an excessive and repeated ingestion of large quantities of protein and alcohol. The large gout-inducing Christmas pie described by Earl Grosvenor was most likely a version of the Yorkshire Christmas-Pie described by Hannah Glasse in her influential cookery book, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy.

To Make a Yorkshire Christmas-Pie

“FIRST make a good standing crust, let the wall and bottom be very thick; bone a turkey, a goose, a fowl, a partridge, and a pigeon, Season them all very well, take half an ounce of mace, half an ounce of nutmegs, a quarter of an ounce of cloves, and half an ounce of black-pepper, all beat fine together, two large spoonfuls of salt, and then mix them together. Open the fowls all down the back, and bone them; first the pigeon, then the partridge; cover them; then the fowls then the goose, and then the turkey, which must be large; season them all well first, and lay them in the crust, so as it, will look only like a whole turkey; then have a hare ready cased, and wiped with a clean cloth. Cut it to pieces, that is, joint it; season it, and lay it as close as you can on one side; on the other side woodcocks, moor game, and what sort of wild-fowl you can get. Season them well, and lay them close; put at least four pounds of butter into the pie, then lay on your lid, which must be a very thick one, and let it be well baked. It must have a very hot oven, and will bake at least four hours. This crust will take a bushel of flour. In this chapter you will see how to make it. These pies are often sent to London in a box, as presents; therefore, the walls must be well built.”

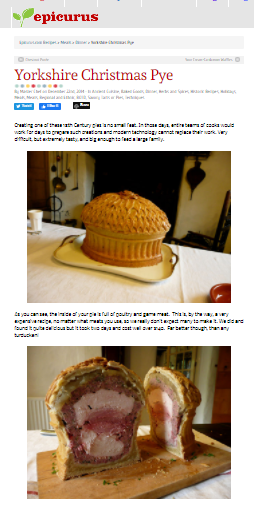

A post entitled “Yorkshire Christmas Pye” in Epicurus describes how tough it was in 2014 to recreate an 18th Century pie. Back then, teams of cooks would work for days to accomplish the feat. According to the chef and author, not even modern appliances could compete with those bygone techniques. The modern pie, from assembly (8 ½ hrs), to baking (4 hrs), to its presentation at the table, took 12 ½ hours in total.

Screenshot of the Epicurus blog page. Photos of the exterior and interior of the Pye made by Ivan Day, whose scrumptuous recreation of Georgian recipes are works of art: Food History Jottings

The Master Chef modified Glasse’s recipe and used the boned meat of the following animals: turkey, goose, partridge, pheasant, woodcock, grouse, and hare. With the added lard in the crust and butter in the filling, I imagine the diner would probably have lacked the energy to push off from the table.

So, inquiring reader, if you are interested in recreating this English pye recipe for Christmas, I encourage you to start dieting on water and vegetables, and exercising on the hour every waking hour to make room for this artery clogging, but very tasty specialty!

“Thank you for the Christmas Cake” was written as a poem by Helen Maria Williams (Read by Tom O’Bedlam)

Patient readers: I apologize for the messy look of the resources list sitting below. The new WordPress “blocks” are wreaking havoc with my ability to publish material on this blog nicely. Obviously I have not learned this “improved” design adequately. I spend more hours fixing problems than writing the article. I assure you, neither Rachel nor Brenda are having this problem. I’ll get the hang of things soon…(I hope.) My comment is this: what was wrong with the old design and, why, if one chooses the classic mode do the blocks keep jumping to the new mode? I’m irked. This is irksome!

Resources:

- “A Miscellany of Christmas Pies, Puddings, and Cakes,” Joanne Major, December 11, 2014. All Things Georgian: Super Sleuths who blog about anything and everything to do with the Georgian Era. This post is filled with informative quotes!

- “Yorkshire Christmas Pye,” Master Chef, December 22, 2014, Epicurus Blog.

- Some Georgian Christmas Fare!,” December 16, 2011,

Julie Day, Countryhousereader Blog. Great information on Christmas food served at an English

country house. Includes information from

Bills of Fare for Christmas feasting, 1805 and the suggested meal courses. - Christmas: Georgian Style! From Norfolk Tales, Myths & More! This rich source and fascinating blog provides detailed information on a Georgian Christmas in this post.

- Twelfth Night Cake, British Food and History, January 5, 2019.

Detailed account of recipes used on that final Christmastide night. - The Englishman’s Plum Pudding, History Today, Maggie Black, Volume 31, Issue 12, December 1981. Includes a history of the British Christmas pudding.

- Mr. Rowlandson’s England, text from Robert Southey,

Illustrations by Thomas Rowlandson. Southey, Robert,

ISBN 10: 0907462774, Published by Antique Collectors Club Ltd, 1985.

I loved this book so much (I read it online at the Internet Archive) that I ordered my own copy. - Letters from England, Volume 1 (of 3), by Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella.

This link provides the online text on Project Gutenberg of Robert Southey’s

first volume, written as a Spanish traveler.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/61122/61122-h/61122-h.htm

Other Christmas posts on this blog:

- Click on this link to find 13 years of covering Christmas in December.

Once again December has caught me flat footed. It is almost 10 days into the month and I am still researching interesting historical information about Christmas holiday celebrations as Jane Austen would have known them. While many books, articles, bloggers and internet sites cover this topic in detail, I hope to add a few interesting items that might not be widely known. I urge you to read Austenonly’s excellent article, “

Once again December has caught me flat footed. It is almost 10 days into the month and I am still researching interesting historical information about Christmas holiday celebrations as Jane Austen would have known them. While many books, articles, bloggers and internet sites cover this topic in detail, I hope to add a few interesting items that might not be widely known. I urge you to read Austenonly’s excellent article, “