by Brenda S. Cox

“Hot! He [John Thorpe’s horse] had not turned a hair till we came to Walcot Church; but look at his forehand; look at his loins; only see how he moves; that horse cannot go less than ten miles an hour: tie his legs and he will get on.”–John Thorpe, Northanger Abbey, chapter 7

“Walcot Church” in Bath is one of several real churches that Jane Austen mentions in her novels. This particular church is closely connected to Jane Austen’s family. Austen made several visits to Bath and lived there for some years, so she knew Bath and its churches and chapels well.

As we’re celebrating Jane Austen’s life this year, we remember that church was an important part of her life. We’ve already looked at some of the churches she attended: St. Nicholas’ at Steventon, where she went as a child, St. Nicholas’ at Chawton, which she attended during the years she was writing most of her novels, and others (see links at the end of those posts).

“Walcot Church”

Walcot Church is the parish church of Walcot, right on the London Road coming into Bath. So it would have marked Thorpe’s arrival at the town. Wealthy and influential people worshipped there during the nineteenth century, so this may also be an indirect boast, as Thorpe tries to connect himself with a prestigious place.

A parish church can be called by the name of the parish or by the name of its patron saint. The patron saint of this church is St. Swithin, so the church is St. Swithin’s Walcot. St. Swithin (also spelled Swithun) was an Anglo-Saxon bishop. The patron saint of Winchester Cathedral, where Jane Austen is buried, is also St. Swithin.

St. Swithin

St. Swithin was associated with various miracles. He came to be connected mostly with the weather. July 15 is St. Swithin’s Day (each saint has a day associated with him or her in the church calendar, usually the day of their death). According to tradition, if it rains on St. Swithun’s day, it will rain for the next forty days, but if it’s clear that day, it will be clear for forty days.

Just before she died, Jane Austen wrote a humorous poem in which St. Swithin threatens Winchester race-goers with rain because they have forgotten him.

Austen’s Parents’ Wedding

How was the Austen family connected with St. Swithin’s?

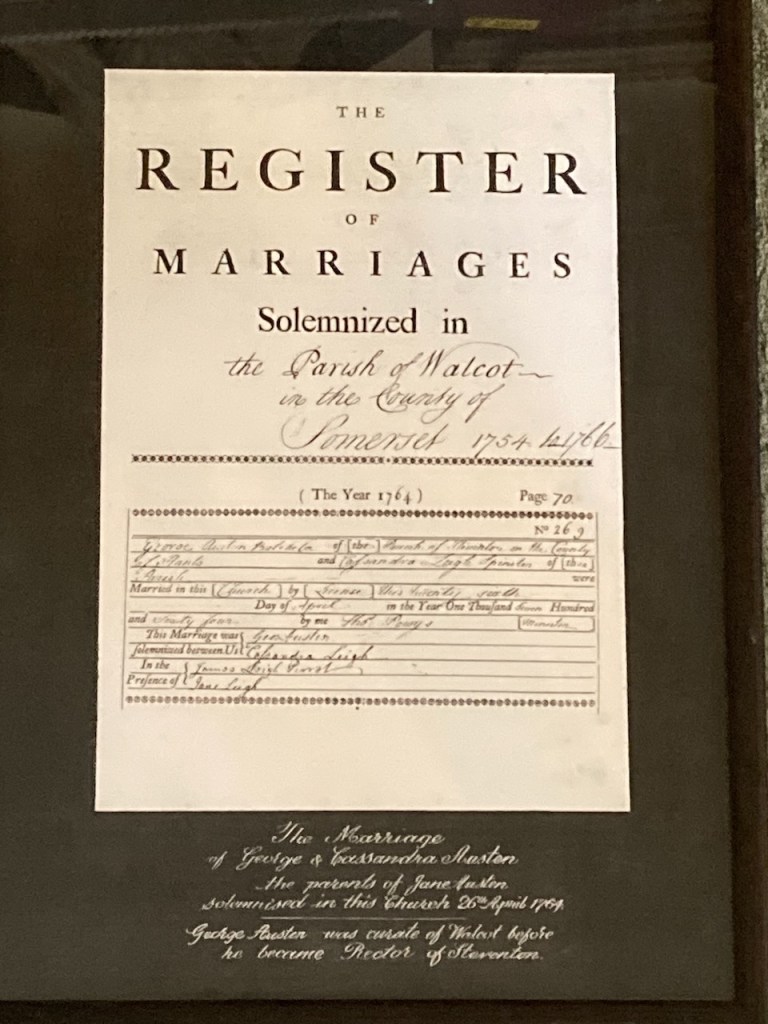

Jane’s father, George Austen, studied at Oxford University. He eventually became an assistant chaplain, then a proctor (in charge of student discipline), called “the Handsome Proctor.” At some point he met Cassandra Leigh, niece of the Master of Balliol College at Oxford. Cassandra was the daughter of a clergyman. Her father eventually retired and moved with his family to Bath. After he died, Cassandra Leigh agreed to marry George Austen, and they were married on April 2, 1764, at St. Swithin’s Church. The register states that Cassandra was living in Walcot parish, while George was in the parish of Steventon in Hampshire. Cassandra’s mother came to the wedding, and her brother, James Leigh-Perrot, and her sister, Jane Leigh, signed as witnesses. George was 32 and Cassandra was 24. They were married by license, presumably a common license, not by banns.

By then George Austen had been ordained and gained the living of Steventon, through his relatives. The young couple went straight to Hampshire, where they rented the parsonage at Deane while the Steventon parsonage was prepared. Of course, Jane Austen was born in 1775 in that Steventon parsonage.

George Austen’s Death

In 1801, George Austen left his Steventon parish to his son’s care and moved to Bath with his wife and two daughters, as his wife’s father had done much earlier. In 1805, George Austen died there. He was buried at St. Swithin’s, where you can still see his grave. Jane Austen wrote to her brother Frank, on Jan. 21 and 22, 1805:

“Our dear Father has closed his virtuous & happy life, in a death almost as free from suffering as his Children could have wished. . . . We have lost an Excellent Father. . . .The funeral is to be on Saturday, at Walcot Church. . . . [his body] preserves the sweet, benevolent smile which always distinguished him.”

Jane did not have a suitor waiting in the wings (as her father had been waiting for her mother in a similar situation). She and her mother and sisters had to depend on her brothers for financial help after her father died.

Did Austen ever attend church at St. Swithin’s? I’ve written another post exploring where she may have gone to church and chapel in Bath. It’s likely that she went to St. Swithin’s when she was visiting her aunt and uncle Leigh-Perrot who lived on the Paragon in Bath. That’s the edge of Walcot parish. The church is a steep walk uphill from their home. Later on, when Jane lived in Bath, she more likely went to chapels closer to her family’s various lodgings.

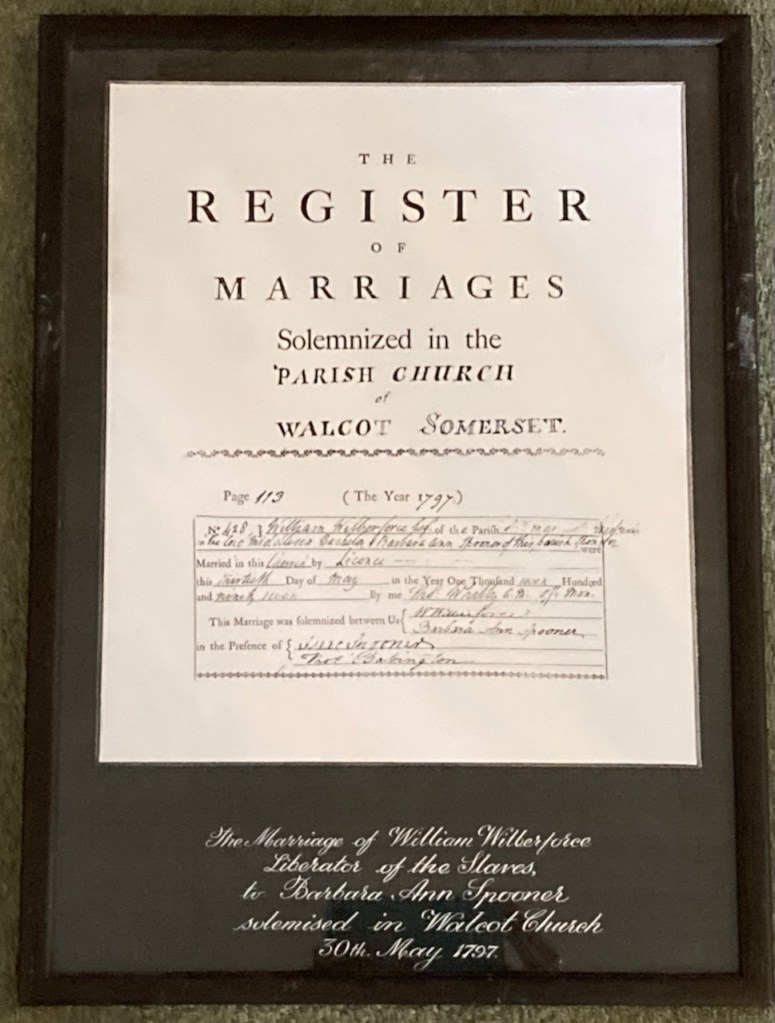

St. Swithin’s is a busy, thriving church today, with many activities going on. Some events of the Jane Austen Festival last fall took place there. The Charles Simeon Trust, started in 1836 by Evangelical clergyman Charles Simeon, is a patron of St. Swithin’s, as well as of Bath Abbey.

Other Churches Mentioned in Northanger Abbey

Northanger Abbey refers to four other real churches or chapels, more obliquely.

Thorpe says he bought his gig from a “Christchurch man.” He is referring to one of the colleges at Oxford University. Oxford and Cambridge are made up of semiautonomous colleges, and a student’s studies were mostly at his own college. Christ Church is a college at Oxford, and its college chapel is also Christ Church Cathedral for the diocese of Oxford. Thorpe shows a cavalier attitude toward “Christchurch” as well as toward everything else.

(A cathedral is the seat of a bishop, who leads a diocese made up of a number of parishes. A parish is a geographical area which was generally served by one main church, like the parishes that Edward Ferrars and Mr. Collins serve.)

Catherine and Isabella expect to worship together in a chapel in Bath; Austen doesn’t tell us which one. It may have been the Octagon Chapel, which would have been convenient to both of them.

Northanger Abbey also indirectly refers to Bath Abbey. Twice the “church-yard” in the center of Bath comes up. The two young men Catherine and Isabella are following go “towards the church-yard,” and later Catherine trips “lightly through the church-yard” to go make her apologies to the Tilneys. This would be the church-yard of Bath Abbey, in the center of Bath. Roger E. Moore, in Jane Austen and the Reformation, argues that Austen purposely did not name the abbey, which was historically the spiritual center of the town. She may have wanted to critique the fact that Bath in her time was a place of pursuing shallow entertainment rather than deeper spirituality.

Near the end of the novel, Catherine is headed home. She looks out for the “well-known spire” of Salisbury. This is ancient Salisbury Cathedral, which has the tallest cathedral spire in England. Her father’s parish is in Salisbury diocese.

While Jane Austen invents country parishes for her characters, she also connects them with spiritual places in the real world.

All images above ©Brenda S. Cox, 2025

Photo by Diego Delso, CC-BY-SA license.

Real Churches in Austen’s Novels and Letters

St. Swithin’s, Walcot and other churches in Northanger Abbey

St. Paul’s, Covent Garden: Actors’ Church

Austen Family Churches

Hamstall Ridware and Austen’s First Cousin, Edward Cooper

Adlestrop and the Leigh Family

Stoneleigh Abbey Chapel and Mansfield Park