Gentle readers, One of my most popular posts is The Dummification of Mansfield Park, which I wrote in response to the 2007 ITV adaptation of Jane Austen’s novel. In addition, Austenprose has been showcasing Mansfield Park during the last two weeks of this month, discussing the novel at length and giving away prizes. A few days ago, Professor Ellen Moody posted her thoughts on Eighteenth Century Worlds about script writer Maggie Wadey’s recent adaptation of Mansfield Park. Once again Ellen has graciously allowed me to post her thoughts, which add another dimension to the latest Jane Austen film adaptation.

Script Writer Maggie Wadey

I know everyone so inveighs against this 2007 Mansfield Park written by Maggie Wadey (in TV the writer is central) and it’s true the film can be seen as a crude outline of a book through hitched-together scenes. The people in charge of this production had not the time, money, nor inclination to begin to present a proper translation of the book. Against the 1983 Mansfield Park this latest adaptation is a laugh. It also (like the 2008 Sense and Sensibility vis-a-vis the 1995 film by Emma Thomspon) imitates the 1999 Mansfield Park: The presentation of Henry and Mary Crawford is simply modeled on the earlier film version – they suddenly appear as a couple, like a pair of witty dolls.

Because of our immediate (and negative) reaction we ignore what is interesting — at least to me. There is a continual atmosphere of menace. One person who commented several times on this film argued that this reaction responded to something going on in Britain right now: a dislike of hierarchy, of artifice, of the older culture of deference. He saw it as deliberately opting for the “natural” in the preference say for a picnic, the eschewing of formality. I can see this but think it’s counteracted by the intense anger that is on the edge of exploding all the time — from the father and the oldest son. The notion of a sensitive temperament unable and unwilling, too gifted and at the same time self-possessed – which partly is in Austen’s characterization of Fanny – is transferred to Edmund (played very well by Blake Ritson). Fanny is presented as subdued because it’s in her interest, not because it’s her nature, and not really because she has been so crushed by the poisonous Mrs Norris. We see her as a tomboy in the opening in a scene taken from Austen’s Northanger Abbey, one which Davies also makes much of in his 2007 Northanger Abbey (anything that can make a woman into a boy is just great; Fanny’s now a horsewoman too, instinctively, not something learned which is what happens in the book and in the 1983 film).

Our first sight of Henry Crawford, he looks out slightly menacing

The scenes of the rehearsal are all dark lit, with a queasy masquerade feel

A typical shot of Fanny during the time of the play: wary, and rightly so (for she is humiliated and marginalized, at the same time as at the center of what goes on)

An implied bullying is at the core of social life in this movie, which uses parties and little physical tussle games (Fanny with children) to provide momentary relief. Lady Bertram opts out but we are made to feel she could hold her own physically and mentally if she wanted to; that’s what I take is the point of making her say she knew all along that Fanny loved Edmund, bringing the happy ending about. (In the 1999 Mansfield Park the taboo is also slurred over, and Mary Crawford at least knows and repeats that Fanny loves Edmund.) I do think both enactments — a natural world against the formality and artifice of hierarchies and the continual bullying, menaces as central to experience — are in reaction to our time.

The proposal scene again has Henry aggressing on Fanny, and her backing away

Sir Thomas's offer of a birthday celebration lacks his usual snarl, but he is saying with implied ability to punish: You must.

Similarly and this is a point brought out in many of the essays of the 1970s: this is a novel which distrusts social life, finds it hollow, treacherous, and seeks the retreat of long-known bonds, truthful affection, and yes quiet, stillness, companionship of hearts and minds.

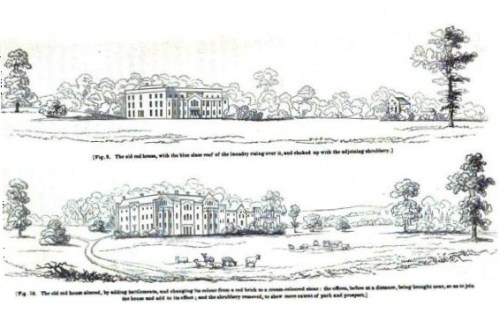

In the original scene of star-gazing in the novel and in the 1983 MP, Fanny and Edmund are to the side of a social group who draw Edmund away:

In the 2007 MP Fanny and Edmund star-gaze to get away from the birthday celebration (which like quite a number of the social occasions in the 2005 P&P are events to escape from):

We have no trip to Portsmouth. Instead Fanny eats, dreams, walks in nature, writes (or tries to write, to communicate is difficult, something to be careful about); and Henry finds her at Mansfield. Here is a typical dialogue when Henry comes upon Fanny alone, looking depressed, but holding still and firm, struggling and enduring as the novel says:

Fanny: “You are tired Mr Crawford.”

Henry: “Oh, I have been too much in society …”

Any news from London she says. He replies “none, no excitement [no war, he likes excitement whatever it be and the list is not attractive), but then he condescends to talk of small matters like Maria and Julia “who are tireless followers of fashion,” “even Edmund is at times at Maria’s where you may know my sister is living at present. Mary’s appetite for society remains undimmed.” The implied outlook on this is scathing. But “Tom, on the other hand, is away from all.” Too away but understandably avoiding what Mary’s appetite seeks. He goes on: “Perhaps living there she is no longer alive to its beauty but to me on a day like this it is an uncommon sight.” She replies: “Oh I think so too I can imagine no where lovelier than Mansfield Park.” There is a feeling of menace when Henry asks her to save him from returning to London.

And then after Tom is brought home very ill, and Edmund and Fanny walk and talk,

Fanny to Henry: “You saw Miss Crawford.”

Henry: “Yes, but not once alone. She was in a pack all the time. She danced a great deal. She spoke a great deal but said nothing sensible or even kind. She was I suppose her London self. Like a stranger with whom I had to argue every little point.”

A still from afar:

The key phrase in the film is given to Edmund (Blake Ritson) when Mary reveals to him her mercenary hopes after Tom’s death and her comment society will “forgive” Maria if they accept her and give enough dinners. He is bitter response: “Society will forgive us. What do I care about society? … I’d have lost you a thousand times rather than see you for what you really are.” That too iss an Austen sentiment; it’s Marianne’s reaction over Willoughby

Edmund listening to Mary.

There is nothing more natural about the kind of personality Bille Piper projects (or Frances O’Connor in the 1999 MP) than there is in the kind of personality Sylvestra Le Touzel portrays (1983); that is, the person who is maimed and made nervous and in need of support and cannot endure to assert herself publicly, especially when she is asked to pretend to be someone or something she’s not is NOT UNNATURAL. It’s just as natural to be quiet, a reader, thoughtful, and perceptive and able to see the other side (which Fanny does) as it is to be noisy, active, not thoughtful, stubborn, and aggressive.

By contrast, The 2001 Aristocrats by Stella Tillyard based on Harriet O’Caroll’s screenplay buys into the sweetness of aristocratic life at the time; it celebrates the artifice and luxury as pleasurable (if overdone in the case of Charles James Fox’s childhood — he takes a bath in cream).

Aristocrats: Caroline reading.

We might say the animating force of The Aristocrats is the opposite to the animating force of the 2007 Mansfield Park: in the first we are led to value artifice, and much of the aesthetics of the upper class in the eighteenth century; and want to have the sweetness of their life (as by the way we are in the 1983 Mansfield Park, which has Chekhovian scenes):

We see the sweetness of life during this long lingering nuanced conversation.

In the second we are not permitted to see these as enjoyable, but only the bullying stance of those in charge. The 1999 Mansfield Park reveals to us the political outlook of these people (Sir Thomas is a conservative; Mrs Norris a sycophant) and how they prey on the powerless (on the slaves). The key character in the 1999 MP is Mrs Price who cannot escape Mr Price as she tells Fanny when they hear his harsh voice requiring her to join him in bed. She married for love.

She married for love.

Ellen

Additional links to other reviews of Mansfield Park 2007:

Read Full Post »