“I had expected to find everything about the place very fine and all that, but I had no idea of its being so beautiful.” –Mrs. Cassandra Leigh Austen, Aug. 13, 1806, on a visit to Stoneleigh Abbey with her daughters Jane and Cassandra

Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays! As my gift to you, let’s take a trip to Stoneleigh Abbey together.

Jane Austen visited Stoneleigh Abbey in 1806. She and her mother and sister were visiting their cousin, Rev. Thomas Leigh, in Adlestrop when his distant cousin, the Honorable Mary Leigh, died. Rev. Thomas inherited the wealthy estate. He took his poorer relations, the Austens, with him to take possession, as a treat for them. They enjoyed it very much, as Mrs. Austen wrote in a letter. She said the house was so large that they needed signposts to find their way, and that it was not only very “fine,” but more beautiful than she had imagined. Catherine Morland, similarly, when she saw Northanger Abbey, “was struck . . . beyond her expectation, by the grandeur of the abbey.”

Based on income, Stoneleigh Abbey was an even grander place than Pemberley or Sotherton (the Rushworth estate in Mansfield Park) would have been. Austen tells us that Darcy’s income was £10,000 a year and Mr. Rushworth’s was £12,000 a year. But the income of the Leighs of Stoneleigh Abbey, in Jane Austen’s time, was even higher, at £17,000 a year, which Victoria Huxley says was “perhaps the annual equivalent of a million pounds in today’s values” (p. 9). (We were told when touring Chatsworth that the income there in Austen’s time was about £30,000, three times Darcy’s income; I haven’t found confirmation of that number anywhere, though.)

Today, ideally you need a car or a tour bus to get you to Stoneleigh Abbey. It is about an hour’s drive north of Oxford or about 40 minutes southeast from Birmingham. If you want to take public transport, it looks like you’ll have a half-hour’s walk at the end of your journey.

I went with the JASNA Summer Tour. We saw the Adlestrop church the same day; it’s only about an hour’s drive away.

Stoneleigh Abbey, like Austen’s fictional Northanger Abbey, is a mix of older monastic buildings and newer buildings. (Newer in Austen’s time, at least.) Let’s take a trip through it, with some quotes from Austen’s novels.

So low did the building stand, that she found herself passing through the great gates of the lodge into the very grounds of Northanger, without having discerned even an antique chimney. . . . To pass between lodges of a modern appearance, to find herself with such ease in the very precincts of the abbey, and driven so rapidly along a smooth, level road of fine gravel, without obstacle, alarm, or solemnity of any kind, struck her as odd and inconsistent.–Catherine Morland, Northanger Abbey

Now we are coming to the lodge-gates; but we have nearly a mile through the park still.–Maria Bertram, Mansfield Park

[Catherine] was hardly more assured than before, of Northanger Abbey having been a richly endowed convent at the time of the Reformation, of its having fallen into the hands of an ancestor of the Tilneys on its dissolution–Northanger Abbey

She was struck, however, beyond her expectation, by the grandeur of the abbey, as she saw it for the first time from the lawn.–Catherine Morland, Northanger Abbey

Even Fanny had something to say in admiration. . . . Her eye was eagerly taking in everything within her reach; . . . being at some pains to get a view of the house, and observing that “it was a sort of building which she could not look at but with respect”–Mansfield Park

Miss Bertram could now speak with decided information of what she had known nothing about when Mr. Rushworth had asked her opinion; and her spirits were in as happy a flutter as vanity and pride could furnish, when they drove up to the spacious stone steps before the principal entrance.–Mansfield Park

An abbey! Yes, it was delightful to be really in an abbey! But she doubted, as she looked round the room, whether anything within her observation would have given her the consciousness. The furniture was in all the profusion and elegance of modern taste.–Catherine Morland, Northanger Abbey

The whole party rose accordingly, and under Mrs. Rushworth’s guidance were shewn through a number of rooms, all lofty, and many large, and amply furnished in the taste of fifty years back, with shining floors, solid mahogany, rich damask, marble, gilding, and carving, each handsome in its way.–Mansfield Park

They returned to the hall, that the chief staircase might be ascended, and the beauty of its wood, and ornaments of rich carving might be pointed out.–Northanger Abbey

The lower part of the house had been now entirely shewn, and Mrs. Rushworth, never weary in the cause, would have proceeded towards the principal staircase, and taken them through all the rooms above, if her son had not interposed with a doubt of there being time enough.–Mansfield Park

The general leads Catherine “into a room magnificent both in size and furniture—the real drawing-room, used only with company of consequence. It was very noble—very grand—very charming!—was all that Catherine had to say, for her indiscriminating eye scarcely discerned the colour of the satin; and all minuteness of praise, all praise that had much meaning, was supplied by the general: the costliness or elegance of any room’s fitting-up could be nothing to her; she cared for no furniture of a more modern date than the fifteenth century.”–Northanger Abbey

“Till midnight, she supposed it would be in vain to watch; but then, when the clock had struck twelve, and all was quiet, she would, if not quite appalled by darkness, steal out and look once more. The clock struck twelve—and Catherine had been half an hour asleep.”–Northanger Abbey

The fireplace, where she had expected the ample width and ponderous carving of former times, was contracted to a Rumford, with slabs of plain though handsome marble, and ornaments over it of the prettiest English china.–Northanger Abbey

A Rumford was an invention that made fireplaces more efficient. They are still used today.

Mr. Elton had retreated into the card-room, looking (Emma trusted) very foolish.–Emma

Of pictures there were abundance, and some few good, but the larger part were family portraits, no longer anything to anybody but Mrs. Rushworth–Mansfield Park

Marianne, who had the knack of finding her way in every house to the library, however it might be avoided by the family in general, soon procured herself a book.–Sense and Sensibility

“What a delightful library you have at Pemberley, Mr. Darcy!”

“It ought to be good,” he replied, “it has been the work of many generations.”

“And then you have added so much to it yourself, you are always buying books.”

“I cannot comprehend the neglect of a family library in such days as these.”–Miss Bingley and Mr. Darcy, Pride and Prejudice

After tea, Mr. Bennet retired to the library, as was his custom–Pride and Prejudice

“My mother is tolerably well, I trust; though her spirits are greatly shaken. She is up stairs and will have great satisfaction in seeing you all. She does not yet leave her dressing-room.”–Jane Bennet, Pride and Prejudice

Fanny’s imagination had prepared her for something grander than a mere spacious, oblong room, fitted up for the purpose of devotion: with nothing more striking or more solemn than the profusion of mahogany, and the crimson velvet cushions appearing over the ledge of the family gallery above. “I am disappointed,” said she, in a low voice, to Edmund. “This is not my idea of a chapel. There is nothing awful here, nothing melancholy, nothing grand.” . . .

Mrs. Rushworth began her relation. “This chapel was fitted up as you see it, in James the Second’s time. Before that period, as I understand, the pews were only wainscot; and there is some reason to think that the linings and cushions of the pulpit and family seat were only purple cloth; but this is not quite certain. It is a handsome chapel, and was formerly in constant use both morning and evening. Prayers were always read in it by the domestic chaplain, within the memory of many; but the late Mr. Rushworth left it off.” . . .

“It is a pity,” cried Fanny, “that the custom should have been discontinued. It was a valuable part of former times. There is something in a chapel and chaplain so much in character with a great house, with one’s ideas of what such a household should be! A whole family assembling regularly for the purpose of prayer is fine!”–Mansfield Park

See my post on The Stoneleigh Abbey Chapel and Mansfield Park for a visit to the chapel with further quotes from Mansfield Park.

In a house so furnished, and so guarded, she could have nothing to explore or to suffer, and might go to her bedroom as securely as if it had been her own chamber at Fullerton.–Catherine Morland, Northanger Abbey

Northanger turned up an abbey, and she was to be its inhabitant. Its long, damp passages, its narrow cells and ruined chapel, were to be within her daily reach, and she could not entirely subdue the hope of some traditional legends, some awful memorials of an injured and ill-fated nun.–Catherine Morland, Northanger Abbey

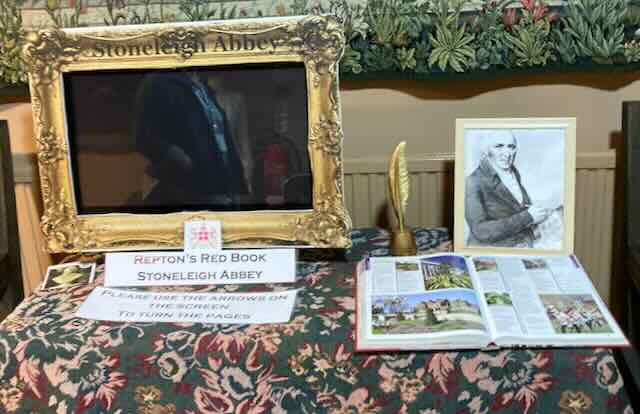

“Smith’s place is the admiration of all the country; and it was a mere nothing before Repton took it in hand. I think I shall have Repton.”–Mr. Rushworth, Mansfield Park

A few steps farther brought them out at the bottom of the very walk they had been talking of; and standing back, well shaded and sheltered, and looking over a ha-ha into the park, was a comfortable-sized bench, on which they all sat down. . . .

“You will hurt yourself, Miss Bertram,” [Fanny Price] cried; “you will certainly hurt yourself against those spikes; you will tear your gown; you will be in danger of slipping into the ha-ha.”–Mansfield Park

In 1946, Stoneleigh Abbey became “one of the first stately homes to open its doors to the public” (Stoneleigh Abbey, 18). A fire destroyed much of it in 1960, though most of the furniture and paintings were rescued. In 1996, a trust was set up to restore it, at a cost of £12 million. They did an amazing job. Restoration was also done on the grounds and the lake. The restoration work sought to improve the habitats of bats, otters, kingfishers, and other species

During their visit, the Austens enjoyed extensive walks through the grounds. Rachel Dodge has posted some of those lovely views. The Austens must have also attended the Stoneleigh Church, St. Mary the Virgin, though we didn’t get to visit it this trip.

I hope you have enjoyed our visit to Stoneleigh Abbey with Jane Austen’s characters, and that you can see it in person some day! This year, the Abbey celebrated Christmas with a Christmas fair and a series of concerts, including carols in the chapel. If you have been to Stoneleigh Abbey, please tell us about your impressions!

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.

All photos in this post, © Brenda S. Cox, 2023.

Sources and Further Reading

Jane Austen & Adlestrop: Her Other Family, by Victoria Huxley. US Amazon link

Stoneleigh Abbey by Paula Cornwell (obtained from Stoneleigh Abbey)

Jane Austen: A Family Record, 2nd ed., by Deirdre Le Faye

The Stoneleigh Abbey Chapel and Mansfield Park

Jane Austen’s Rich(er) Leigh Family Connections at Adlestrop and Stoneleigh Abbey

Cassandra Leigh Austen’s Stay at Stoneleigh Abbey (letter)

Jane Austen’s Leigh Family: Stories Behind the Stories

Jane Austen’s Clergymen and Her Leigh Family

Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park and Stoneleigh Abbey

More pictures of Stoneleigh village, church, and abbey

Stoneleigh Abbey website