The Antique Prints Blog offers a wonderful post about Ackermann’s Print Shop with excellent illustrations. I will definitely be visiting this site often!

Archive for the ‘Regency Art’ Category

Seen Over the Ether: Antique Prints Blog

Posted in jane austen, Jane Austen's World, Regency Art, Regency World, tagged Ackermann Print Shop, Antique Print Shop, Seen over the ether on March 30, 2010| 4 Comments »

Regency Window Treatments: Ackermann Plates

Posted in Architecture, jane austen, Regency Art, Regency Life, Regency Period, Regency style, tagged Ackermanns Repository, Regency furniture, Regency Interiors, Regency window treatments and draperies, Window treatments 1815-1820 on March 26, 2010| 7 Comments »

Ah, spring. Time to open the windows and air the rooms … and to consider redecorating. Ackermann’s Repository (1809-1829) didnt just cover fashion. The magazine also featured furniture and embroidery patterns, for example, and window treatments. This is simply a visual post. Enjoy!

The Botanical Prints of Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759-1840)

Posted in art, jane austen, Jane Austen's World, Napoleon, Regency Art, Regency Period, Regency style, Regency World, tagged botanical prints, flower prints, Jospehine Bonaparte, Pierre-Joseph Redouté, Rose engravings, rose watercolors on November 11, 2009| 12 Comments »

Pierre-Joseph Redouté’s flower prints are so lush and detailed that you can almost pick the flowers off the page. In the famous rose print below, a single drop of water rests exquisitely on a rose petal of the top rose. Born in a family of artists*, Pierre-Joseph became known as the premier botanical illustrator of his day (indeed, to this day). His influence spread far and wide and can be still felt in illustrations on cards, decorative boxes, books, wallpapers and prints, and calendars.

The watercolor images in this post were taken from his famous book of prints, Les Roses. Redouté, known as the “Raphael of flowers, mastered the technique of stipple engraving- in which he uses tiny dots, rather than lines, to create engraved copies of his watercolor illustrations. This new technique allowed him to make subtle variations in coloring (see the detail of the magnolia in the last image below).

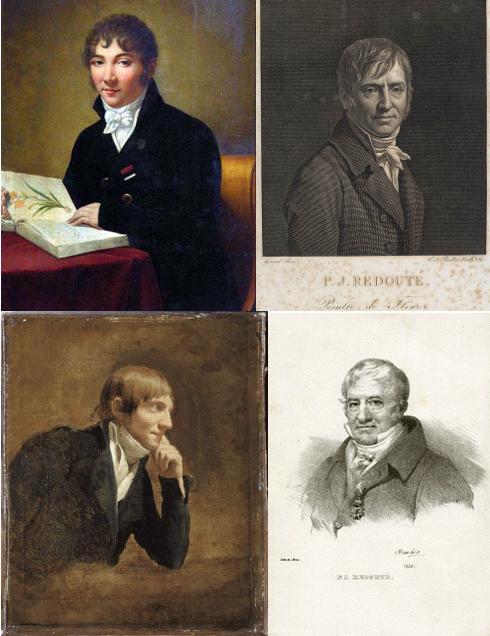

The four faces (and ages) of Pierre-Joseph Redouté

Redouté completed the three volumes of Les Roses, his best known work, between 1817 and 1824. His most popular illustrations are assembled in Les Liliacées (486 watercolors); and Les Roses (169 watercolors). Hand-colored stipple engravings, such as the magnolia sitting at the bottom of this post, were made from these watercolors. – Discovery Editions

Josephine, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, was known for her spectacular garden at Chateau de Malmaison, where exotic plants were cultivated. The plants, acquired from around the world, were documented by France’s leading horticulturists and botanists, and painted by Pierre-Joseph Redouté.

Josephine, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, was known for her spectacular garden at Chateau de Malmaison, where exotic plants were cultivated. The plants, acquired from around the world, were documented by France’s leading horticulturists and botanists, and painted by Pierre-Joseph Redouté.

Detail of the magnolia engraving below.

- The Floral Art of Pierre Joseph Redoute by Marianne Roland Michel, Peter C. Sutton, Carolyn Rose Rebbert, 2002

- George Glazer Gallery

- Illustration in book

- Trouvais

- Rose Prints

- A Picture of Roses

- Dictionary of painters and Engravers, 1889 By Michael Bryan, Robert Edmund Graves

- Les Liliacees, Cincinnati Historical Society Library

Whistlejacket by George Stubbs

Posted in jane austen, Regency Art, tagged George Stubbs, Whistlejacket on May 30, 2008| 3 Comments »

What could be more magnificent to a Georgian gentleman than a fine stallion with fiery eyes and beautiful confirmation (musculature), a thoroughbred horse known to have won an important race and who could sire other champions? George Stubbs, a painter who specialized in horse and dog portraiture, painted Whistlejacket on commission for the Marquess of Rockingham in 1762. When it isn’t on loan to another museum (this oil painting is on exhibit in York through August) this arresting, iconic, and almost life-sized image hangs in the National Gallery in London.

Whistlejacket was foaled in 1749, and his most famous victory was in a race over four miles for 2000 guineas at York in August 1759. Stubbs’s huge picture was painted in about 1762 for the 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, Whistlejacket’s owner and a great patron of Stubbs. According to some writers of the period the original intention was to commission an equestrian portrait of George III, but it is more likely that Stubbs always intended to show the horse alone rearing up against a neutral background. (Description of the painting on the National Gallery website, image from Wikimedia Commons)

George Stubbs was born in 1724 in Liverpool. Largely a self-taught painter, his fame among aristocratic horseman and sportsmen as a painter of animals was at his height when Jane Austen began to write First Impressions. The artist’s interest in horse and human anatomy equalled his interest in painting, and he studied the subject to such an extent that he was commissioned to illustrate a book on midwifery in 1751 by Dr. John Burton. His ground-breaking book, the Anatomy of a Horse, was published in 1766. Stubbs, whose paintings hung in the private collections of the great houses of his aristocratic patrons, and who was highly regarded in these circles, as well as among the naturalists of his day, did not find general fame until he was rediscovered in the 20th century. To this day, most of Stubbs’s painting remain in private collections.

The origin of the name, Whistlejacket, is interesting. In Yorkshire, the local name for the treacle/gin drink was ‘whistle-jacket’. When made with brandy instead of gin, the color of the drink would have resembled the color of this palomino stallion’s coat.

The painting is more like a candid photograph, capturing the essence of the horse’s beauty and energy in a split-second shot. The horse is sensuous with its chestnut gleam and rounded, muscular form. Whistlejacket’s eye does not meet the viewer’s; instead, it seems to look inward, contemplating. (Art Straight From the Horse’s Mouth)

To read more about George Stubbs (1724-1806), click on the links below:

- Listen to a podcast or read about The Anatomy of a Horse on NPR’s Engines of Our Ingenuity

- George Stubbs on Brits at Their Best

- Click here to see a reproduction of the painting in an outdoor exhibition in London, The Grand Tour, Image #8.

Silhouettes: Tracing the Poor Man’s Portrait in the 18th & 19th Centuries

Posted in jane austen, Jane Austen's image, Regency Art, Regency style, Regency World, tagged john miers, portraits, robert burns, sense and sensibility 1995, Silhouette on April 22, 2008| 6 Comments »

Jane fans are familiar with images of her distinctive profile (left), and her sister Cassandra’s silhouette (right.) In the 18th and 19th centuries the silhouette was a popular form of

Jane fans are familiar with images of her distinctive profile (left), and her sister Cassandra’s silhouette (right.) In the 18th and 19th centuries the silhouette was a popular form of portraiture with families and individuals who could not afford a more formal and expensive mode of having their likenesses made. Oil paintings required several sittings, and even pastels or watercolours took time. Silhouettes were created in one quick sitting, and were therefore affordable.

A complicated silhouette with painted touches, such as Cassandra’s, would take a skilled artist like John Miers a reputed three minutes to produce. With such speed, a silhouettist working in a crowded area could create enough portraits to make a decent living at a penny a likeness.

Silhouettes were so easy to trace with tracing machines or by hand that amateurs could also make them. In Sense and Sensibility 1995, Willoughby is shown sitting for his portrait. Marianne, who was no professed artist, laboriously drew Willoughby’s profile using two sets of grids, one for Willoughby’s screen and one for her drawing pad, and well-placed candles that cast his profile against the screen. (See image at top of page in this link.)

Unfortunately Willoughby grew impatient (or amorous), and he peeked around the screen to flirt with Marianne. When he returned to his seat, his profile had shifted on the grid (see first and last image.) For an amateur, such a shift would have been disastrous. A skillful silhouettist would have been finished before Willoughby moved.

Most silhouette artists were itinerants who worked their magic in popular tourist spots, such as Brighton or Bath, or at public fairs, where people were apt to buy souvenirs. They either traced profiles by hand and painted them in, or skillfully snipped away at the paper with sharp scissors. With an experienced artist, the second method would have been fast and accurate.

Some silhouettes, such as this example of the Austen family on the JASNA site could be fairly complicated. Still others, such as those set in the rings and brooches on the Wigs on the Green website, were extremely small. The title of this post is somewhat of a misnomer, since both the rich and poor were enamored with these portraits, but while the rich could afford to commission sumptuous paintings in addition to these shades, a silhouette likeness was all a poor person could afford.

John Miers is considered the premier silhouette artist of the 18th century. His skillful shades (and those of his followers) are represented in the National Portrait Gallery and the Victoria And Albert Museum. Collectors prefer Miers’ earlier likenesses, which showed a delicacy of touch and painting that are unequaled. The artist, who lived in Edinburgh, also snipped John Burns’s profile. Click here to view: Robert Burns’s Appearance.

To learn more about silhouettes, click on the following links:

- My other post on this topic: Tracing Jane Austen’s Shade

- Etienne de Silhouette: The silhouette was named after this Frenchman, but he was not well liked in his time.

- Candice Hearn: Georgian Painted Silhouettes: Beautiful examples and a great explanation.

- Silhouette History: Includes a fascinating tale of Etienne de Silhouette, Finance Minister of France, who liked to cut paper silhouettes but who ignored the plight of the poor.

- Historical Time Period of the Silhouette: Includes a description of how silhouettes were made during the 18th century, which is distinctly different from cutting the silhouette.

- Silhouette Cutting in the Early 19th Century: The Silhouette Parlor: This website provides a clear, concise explanation of silhouettes and examples

- Robert Burns’ Clarinda: John Miers cut a silhouette of Robert Burns’ mistress. The story is as fascinating as the portrait.

- Paper Profiles: American Portraits in the Silhouette, Penley Knipe, Stanford – This article provides a detailed history and explanation of the silhouette.

- Shades and Silhouette Pictures: Penley Knipe describes the materials and techniques used in American portrait silhouettes.

This three-minute YouTube clip of a silhouette artist demonstrates how quickly silhouettes are made. It also includes a short history of silhouette making.