Inquiring Readers: Who knew? Jane Austen not only viewed works of art when visiting London, in one letter she spoke particularly well of a painting by Benjamin West, a successful American transplant in that city, whose major patron was King George III..

Austen’s Opinion About “Christ Rejected”

During a first visit to her Brother Henry’s new house in Hans Place, Austen wrote a letter to her dear friend Martha Lloyd. Whenever Jane visited London, she attended parties and balls, plays, and concerts. She also went shopping in a major way, and brought a list of items that friends and relatives wanted her to purchase for them. In this letter (109, as listed by Deirdre Le Faye in her Fourth Edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, and dated September 2, 1814) Jane mentions (among many other things) a painting she’d recently viewed.

Jane Austen was taken by the image of Christ in this painting. Image from Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

“I have seen West’s famous Painting, & prefer it to anything of the kind I ever saw before. I do not know that it is reckoned superior to his “Healing in the Temple”, but it has gratified me much more, & indeed is the first representation of our Savior which ever at all contented me. His “Rejection by the Elders”, is the subject.–I want to have You & Cassandra see it.”

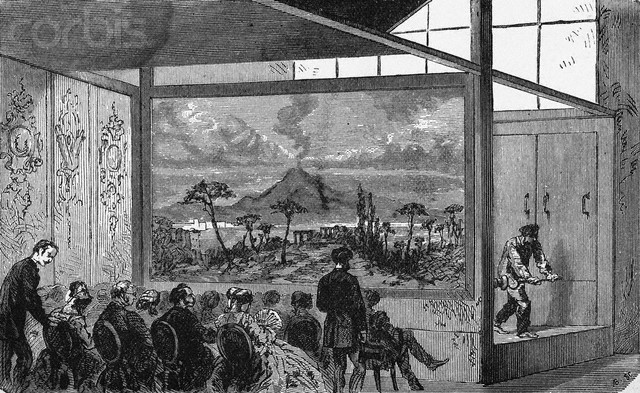

Jane was writing about “Christ Rejected by the Jews”, now hanging at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1814, when this enormous and complicated painting was exhibited from June to late fall, and when Austen was visiting Henry, it hung in the “former” Royal Academy at 125 Pall Mall. Visitors were given a 3-page description of the work, which was filled with information about each of the characters in the painting. In the past, panoramas, dioramas, and tableaus, like those created by Emma Hamilton, were popular Georgian entertainment.

Austen mentions that not only did this painting gratify her, but that this was the “first representation of our Savior which ever at all contented me.” She wanted her best friend, Martha, and her beloved sister, Cassandra, to view the painting in person. Ellen Moody in Reveries Under the Sign of Austen, Two mentions that this was:

“A highly unusual passage for Jane Austen: she has been talking about what tastes she likes and by association (how the letters proceed) she moves to discourse about solemn religious painting done in the grand historical style. I suggest Martha liked these or mentioned them in her letter. For Jane’s part, in this sort of picture what she likes best is Christ Rejected. Martha seems to have wanted to know if Christ Healing the Sick is considered superior — hinting perhaps that she, Martha, preferred it.”

In fact, Moody states that this is the first time the reader reads explicitly religious language from Austen, when she mentions “Our savior.” Food for thought from a clergyman’s devoted & religious daughter.

Who Was Benjamin West?

Benjamin West hardly raised a blip in my Art History courses, although he was a prominent painter during his life and in Great Britain. His paintings have not stood the test of time, but during his heyday, he was King George III’s favorite historical painter. And, so, when he moved to London in 1763, he established his atelier and metier within 5 years of his move to that great city. King George’s patronage ensured West’s success. He became the second President of the Royal Academy of Arts in London from 1792 until his death in 1820 at 81. His enormous neoclassical paintings do not make my heart soar, although I find his portraits, especially his self-portraits, interesting and masterful. (Hover cursor over the portraits for details.)

Austen’s mention of “Christ Healing the Sick in the Temple”

This painting was not Austen’s favorite of the two, however, its immense popularity drew crowds. It has an interesting and convoluted history. From Jane’s excerpt in her letter, she found the latter painting of ‘Christ Rejected” more meaningful. West, however, was so attached to this painting that he created a second version that he donated to a Pennsylvania Hospital. Interestingly

Christ Healing. Small image from Portraits in Revolution

“On its [first] completion in 1811 it was exhibited in London to immense crowds, and was subsequently purchased by the British Institution for 3,000 guineas — the largest sum ever paid for a modern work.”

And so West painted another version, with an “improved composition”, which he sent to the Pennsylvania Hospital (where it still resides, with this partial note:

“Mr. West bequeaths the said picture to the Hospital in the joint names of himself and his wife, the late Elizabeth West, as their gratuitous offering and as a humble record of their patriotic affection for the State of Pennsylvania, in which they first inhaled the vital air — thus to perpetuate in her native city of Philadelphia the sacred memory of that amiable lady who was his companion in life for fifty years and three months.”

I could not find a public domain, copy right free image of this painting. This link leads to a high quality image of “Christ Healing the Sick.” and information about the painting.

Conclusion:

Austen’s letters add so much flavor to our knowledge about her life, thoughts, and novels. I highly recommend that all Austen devotees read every letter that has been printed, starting with Deirdre Le Faye’s masterwork, the compilation of Jane Austen’s Letters.

More about this topic

- Self Portrait, copy, Wikimedia Commons Benjamin West – Wikipedia. Acquired from this site with the following information: After Benjamin West, Self-Portrait of Benjamin West, 1776. Currently at the Baltimore Museum of Fine Art.

- Christ Healing the Sick in the Temple, Portraits in Revolution

- Jane Austen Letter 109

- Benjamin West – Biography and Legacy: The Art Story

- Betrayal: Jane Austen’s Imaginative Use of America, Patricia Ard, Persuasions On-Line, Jane Austen Society of North America, V33, No1 (Winter 2012)