Inquiring Readers: This is the second of four posts to Pride and Prejudice Without Zombies, Austenprose’s main event for June/July – or an in-depth reading of Pride and Prejudice. My first post discussed Dressing for the Netherfield Ball. This post discusses the dances and etiquette of balls in Jane Austen’s era. Warning: the film adaptations get many dance details wrong.

So, he enquired who she was, and got introduced, and asked her for the two next. Then, the two third he danced with Miss King, and the two fourth with Maria Lucas, and the two fifth with Jane again, and the two sixth with Lizzy, and the Boulanger …” Mrs Bennet about Mr. Bingley at The Netherfield Ball.

The English ballroom and assembly room was the courting field upon which gentlemen and ladies on the marriage mart could finally touch one another and spend some time conversing during their long sets or ogle each other without seeming to be too forward or brash. Dancing was such an important social event during the Georgian and Regency eras that girls and boys practiced complicated dance steps with dancing masters and learned to memorize the rules of ballroom etiquette.

Balls were regarded as social experiences, and gentlemen were tasked to dance with as many ladies as they could. This is one reason why Mr. Darcy’s behavior was considered rude at the Meryton Ball- there were several ladies, as Elizabeth pointed out to him and Colonel Fitzwilliam at Rosings, who had to sit out the dance.

“He danced only four dances, though gentlemen were scarce; and, to my certain knowledge, more than one young lady was sitting down in want of a partner.”

Mr. Bingley, on the other hand, danced every dance and thus behaved as a gentleman should.

Ladies had to wait passively for a partner to approach them and when they were, they were then obliged to accept the invitation. One reason why Elizabeth was so vexed when Mr. Collins, who had solicited her for the first two dances at the Netherfield Ball, was that she’d intended to reserve them for Mr. Wickham. Had she refused Mr. Collins, she would have been considered not only rude, but she would have forced to sit out the dances for the rest of the evening.

The only acceptable excuse in refusing a dance was when a lady had already promised the next set to another, or if she had grown tired and was sitting out the dance. Elizabeth could offer neither excuses at the start of the ball, and thus was forced to partner with Mr. Collins.

At a ball, a lady’s dress and deportment were designed to exhibit her best qualities:

As dancing is the accomplishment most calculated to display a fine form, elegant taste, and graceful carriage to advantage, so towards it our regards must be particularly turned: and we shall find that when Beauty in all her power is to be set forth, she cannot choose a more effective exhibition – The Mirror of Graces, 1811

It was also extremely important for a gentleman to dance well, for such a talent reflected upon his character and abilities. Lizzie’s dances with Mr. Collins were causes of mortification and distress.

“Mr. Collins, awkward and solemn, apologising instead of attending, and often moving wrong without being aware of it, gave her all the shame and misery which a disagreeable partner for a couple of dances can give. The moment of her release from him was exstacy.”

A gentleman could not ask a lady to dance if they had not been introduced. This point was well made in Northanger Abbey, when Catherine Morland had to sit out the dances in the Upper Rooms in Bath, for Mrs. Allen and she did not know a single soul. Mrs Allen kept sighing throughout the evening, “I wish you could dance, my dear, — I wish you could get a partner.” Mr. Tilney was introduced by Mr. King, the Master of Ceremonies in the Lower Rooms, to Catherine, who could then dance with him. At Rosings, when Mr. Darcy explained to Lizzie that he danced only four dances at the Meryton Assembly ball because he knew only the ladies in his own party, she scoffed and retorted: “True; and nobody can ever be introduced in a ball room.”

Because a ball was considered a social experience, a couple could (at the most) dance only two sets (each set consisted of two dances), which generally lasted from 20-30 minutes per dance. Thus, a couple in love had an opportunity of spending as much as an hour together for each set.

A gentleman, whether single or married, was expected to approach the ladies who wished to dance. Given the etiquette of the day, Mr. Elton’s refusal to dance with poor Harriet at the Crown Ball in Emma was rude in the extreme, but Mr. Knightley performed his gentlemanly duty by asking that young lady to dance (and winning her heart in the process).

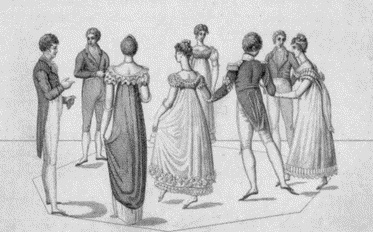

Regency dances were extremely lively. The dancers were young, generally from 18-30 years of age, and they did NOT slide or glide sedately, as some recent film adaptations seem to suggest. They performed agile dance steps and exerted themselves in vigorous movements which included hopping, jumping, skipping, and clapping hands.

Depending on the dance formation and steps, a gentleman was allowed to touch a lady and hold her hand (and vice versa, as shown in the example of Mansfield Park 1999 above and in the image below).

The couple had many opportunities to converse or catch their breaths when they waited for others to finish working their way down a dance progression. The ability to carry out a conversation was considered very important, as Lizzie pointedly reminded Mr. Darcy:

“Elizabeth … took her place in the set, amazed at the dignity to which she was arrived in being allowed to stand opposite to Mr. Darcy, and reading in her neighbours’ looks their equal amazement in beholding it. They stood for some time without speaking a word; and she began to imagine that their silence was to last through the two dances, and at first was resolved not to break it; till suddenly fancying that it would be the greater punishment to her partner to oblige him to talk, she made some slight observation on the dance. He replied, and was again silent. After a pause of some minutes, she addressed him a second time with:

“It is your turn to say something now, Mr. Darcy.—I talked about the dance, and you ought to make some kind of remark on the size of the room, or the number of couples.”

He smiled, and assured her that whatever she wished him to say should be said.

“Very well.—That reply will do for the present.—Perhaps by and by I may observe that private balls are much pleasanter than public ones.—But now we may be silent.”

“Do you talk by rule then, while you are dancing?”

“Sometimes. One must speak a little, you know. It would look odd to be entirely silent for half an hour together, and yet for the advantage of some, conversation ought to be so arranged as that they may have the trouble of saying as little as as possible.”

The dances that would have been danced at the Nethefield Ball were:

The English Country Dance

The characteristic of an English country dance is that of gay simplicity. The steps should be few and easy, and the corresponding motion of the arms and body unaffected, modest , and graceful. – The Mirror of Graces, 1811

Country dances consisted of long lines of dances in which the couples performed figures as they progressed down the line.

When a dancer was too tired to do steps, she would have been considered no longer dancing at all, as with Fanny in Chapter 28 of Mansfield Park:

“Sir Thomas, having seen her walk rather than dance down the shortening set, breathless, and with her hand at her side, gave his orders for her sitting down entirely.”

Rather than everyone starting at once, dances would have called and led off by a single couple at the top; as that couple progressed down the set other couples would begin to dance, then lead off in turn as they reached the top, until all the dancers were moving. Jane Austen occasionally got to lead a dance, as she mentioned in a letter of November 20, 1800, to her sister Cassandra:

“My partners were the two St. Johns, Hooper, Holder, and very prodigious Mr. Mathew, with whom I called the last, and whom I liked the best of my little stock.”

This could lead to very long dances indeed (half an hour to an hour) if there were many couples in a set” – What Did Jane Austen Dance?

The Cotillion

The cotillion was based on the 18th-century French contradanse and was popular through the first two decades of the 19th century. It was performed in a square formation by eight dancers, who performed the figure of the dance alternately with ten changes.

The rapid changes of the cotillion are admirably calculated for the display of elegant gayety, and I hope that their animated evolvements will long continue a favourite accomplishment and amusement with our youthful fair. – The Mirror of Graces

The minuet.

This dance had grown almost out of fashion by the time A Lady of Distinction wrote The Mirror of Graces, and it is conjectured that Jane Austen must have danced it in her lifetime.

Boulanger

Boulangers, or circular dances, were performed at the end of the evening, when the couples were tired. Jane Austen danced the boulanger, which she mentioned in a letter to Cassandra in 1796: “We dined at Goodnestone, and in the evening danced two country-dances and the Boulangeries.”

Note: the Quadrille and the waltz would not have been danced at the Netherfield Ball. Jane did mention the quadrille in a letter to Fanny Knight, which was dated 1816. And the waltz would not have been regarded an acceptable dance in 1813. It is doubted that Jane ever waltzed. The reel might have been danced at the Meryton Assembly, or at a private dance given by Colonel Foster and his wife, for instance, but it would probably not have been featured at the Netherfield Ball at the same time as a country dance.

Second Note: The movies have it all wrong. According to the author of this post on Capering and Kickery, “Real Regency Dancers Are Au Courant

Along with the peculiar notion that dance figures from the 17th century are useful for the early 19th century comes the even more peculiar notion that entire dances of that era are appropriate. Regency-era dancers were not interested in doing the dances of their great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandparents, any more than today’s teenagers are. Dances like “Hole in the Wall” and “Mr. Beveridge’s Maggot” were written in the late 17th century. Their music is completely inappropriate for the Regency era. Their style is inappropriate. Their steps are inappropriate. There is no sense in which these dances belong in the Regency era. Loving obsessions with these dances make me want to cry at the sheer ignorance being promulgated by the people who keep putting these dances in movies.”

More on the Topic