Copyright (c) Jane Austen’s World. Inquiring reader: Tony Grant sent me images of Hans Place by way of a personal tour. I am sure he won’t mind my sharing his photos of one of the areas that Jane Austen stayed in when she visited her brother Henry in London. In addition, I have elaborated on other places where Jane Austen lodged when she spent time in London.

Jane visited London as early as 1796. Constance Hill writes in her 1901 book, Jane Austen: Her Homes and Her Friends:

MISS JANE AUSTEN’S acquaintance with London began at an early date, as she frequently passed a few days there when journeying between Hampshire and Kent.

We have mentioned her sleeping at an inn in Cork Street in 1796. Most of the coaches from the south and west of England set down their passengers, it seems, at the “White Horse Cellar” in Piccadilly, which stood near to the entrance of what is now the Burlington Arcade. Jane and her brothers, therefore, probably alighted here and they would find Cork Street, immediately behind the “White Horse Cellar,” a convenient place for their lodging.

Jane visited Town on numerous occasions and stayed with her favorite brother, Henry, and his wife Eliza. Henry not only actively supported his sister’s writing career, but served as her agent, negotiating on her behalf with publishers and printers. When a book required editing and proofing, Jane would visit Henry to accomplish these ordinary, rather time-consuming tasks, Kathryn Sutherland’s opinions notwithstanding.

This post details her visits through Henry’s many moves as he experiences successes and tribulations in his professional and married life. In his varied career Henry served as a soldier in the Oxfordshire militia (1793-1801), a London banker (1801?-1816), and as a curate at Chawton from 1816.

Jane’s visit to Sloane Street, 1811

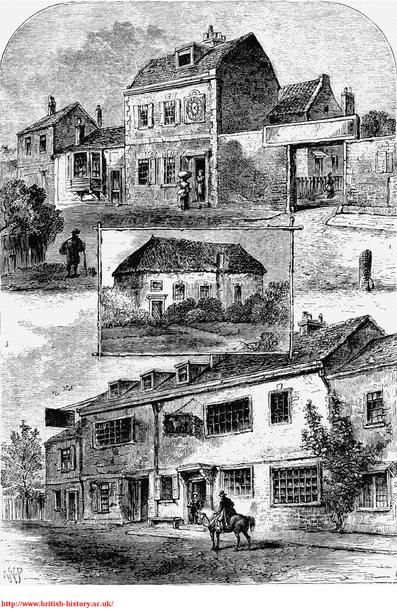

When Jane Austen visited her brother Henry in 1811, he lived in Sloane Street (today behind Harrods in Knightsbridge). At the time, the street was a wide thoroughfare that connected Knightsbridge with the west part of Pimlico and the east end of Chelsea. The area was still quite rural, for there was no development at the east side of Sloane Street before 1790. In the late 18th century, the approach to London from this side was still regarded as a dangerous, for the area was rural and dimly lit. Chelsea, in fact, had just recently begun to be engulfed by a burgeoning London, but during Jane Austen’s day, the area was still quite bucolic and rural, as these images attest.

Cheyene Walk, London, late 18th c., early 19th century, People strolling by the banks of the River Thames, in the distance is Chelsea Old Church

In 1796, the Old Dairy was erected, for cows still grazed nearby. The community was filled with gardens, in particular the Physic Garden founded in 1673 by the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries. Throughout these spacious grounds, apprentices learned to identify plants.

Ranelagh Gardens opened to the public in 1742 as a premier pleasure garden, popular with the wealthy and anyone who could afford a ticket.

King’s Road, so named in the day of King Charles IIs, was actually a private road that dated back to 1703. It connected Westminster to Fulham Palace, where he took a boat to Hampton Court. King Charles also used the road to visit his mistress Nell Gwyn. At this time, the royal palace was at Hampton Court and Chelsea was known as the Hyde Park on Thames.

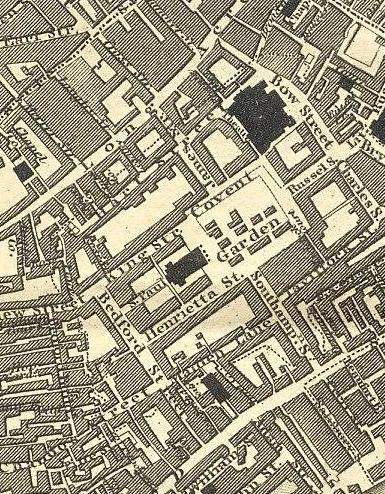

By the time Henry Austen moved to Sloane Street the neighborhood had changed enough for Jane to experience pleasant society, although ten years after Jane’s death, Greenwood’s Map (1827) still showed many empty lots and gardens in the vicinity. (See map above.)

While living in Sloane Street, Henry was a successful man:

Henry and two associates had founded a banking institution in London sometime between 1804 and 1806. Austen, Maunde and Tilson of Covent Garden flourished and enabled Henry and Eliza to move from Brompton (where Jane Austen had found the quarters cramped during a visit in 1808) to a more fashionable address and larger house at 64 Sloane Street. Jane’s visits here in 1811 and 1813 were happy events, filled with parties, theatre-going, and the business of publishing Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice. – Henry Austen: Jane Austen’s “Perpetual Sunshine” by J. David Grey

When visiting her brother, Jane would venture into Town to shop and visit the theatre (Read Tony Grant’s article about Jane Austen and the Theatre). Henry and Eliza were a fun-loving and popular couple, and from Jane’s description in a letter below, they knew how to throw a party:

“Our party went off extremely well. The rooms were dressed up with flowers, &c., and looked very pretty. . . . At half-past seven arrived the musicians in two hackney coaches and by eight the lordly company began to appear. Among the earliest were George and Mary Cooke, and I spent the greatest part of the evening very pleasantly with them. The drawing-room being soon hotter than we liked, we placed ourselves in the connecting, passage, which was comparatively cool, and gave us all the advantage of the music at a pleasant distance, as well as that of the first view of every new comer. I was quite surrounded by acquaintance, especially gentlemen.”

She went on to describe the music as extremely good and “included the glees of ‘Rosabelle,’ ‘The Red Cross Knight,’ and ‘Poor Insect.’ Wiepart played the harp and Miss Davis, all dressed in blue, sang with a very fine voice.”

Henrietta Street, 1813

In 1813, Henry, who was four years older than Jane, lost his wife after a painful and debilitating illness. In contrast, his Uncle Leigh Perrot and brother Edward helped to secure his appointment as Receiver-General for Oxfordshire, a most definite honor. Soon after Eliza’s death, Henry moved to rooms over Tilson’s bank on Henrietta Street in Covent Garden, a location more centrally located in London.

Both Jane and Fanny Knight, their niece, visited him there in the spring of 1814, when Mansfield Park was with the publisher.

As was the custom, Jane brought lists of items to purchase in Town for those who had remained behind in the countryside. In her biography, Constance Hill writes about Jane’s shopping experience:

“I hope,” she writes to her sister, “that I shall find some poplin at Layton and Shear’s that will tempt me to buy it. If I do it shall be sent to Chawton, as half will be for you; for I depend upon your being so kind as to accept it . . . It will be a great pleasure to me. Don’t say a word. I only wish you could choose it too. I shall send twenty yards.” Layton and Shear’s shop, we find, was at 11, Henrietta Street, Covent Garden.

Hans Place, 1814

In 1814, Henry moved from his rooms above his bank to a house he purchased in Hans Place in Knightsbridge. The area was situated near his old quarters on Sloane Street, where he and his wife had spent such a pleasurable time together.

Today, the area, developed by Henry Holland, looks much different than when Jane and Henry knew it (see the image below), but the gardens are not much changed.

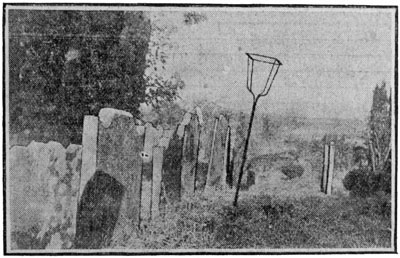

Jane found #23 Hans Place delightful and Henry’s new house more than answered her expectations. She also admired the garden greatly. In the early part of the 19th century, Sloane Square was an open space enclosed with wooden posts, connected by iron chains. (British History Online)

In Hans Place, Jane had the use of a downstairs room that opened onto the garden, and she describes her pattern of working indoors, then taking a break in the garden: “I go & refresh myself every now & then, and then come back to Solitary Coolness.” I like Claire Tomalin’s comment in her biography of Jane Austen (1997) that this is “very much what someone settling down to write does, getting up, pacing, thinking, returning to the page she is working on.” – My Long Jumble, Sarah Emsley

Jane visited Henry in Hans place twice, once in 1814, and for a more extended period from October to December in 1815, when she was preparing Emma for publication. During this visit, Henry became seriously ill and Jane nursed him back to health. She also famously visited the Prince Regent’s library at Carlton House during Henry’s recuperation.

Constance Hill writes in her biography: “… we are also told “that Hans Place” was then “nearly surrounded by fields…We hear of a small evening party to be given in Hans Place whilst Fanny is staying there with her aunt. After describing the morning engagements, Jane writes: “Then came the dinner and Mr. Haden [the apothecary who was instrumental in arranging Jane’s invitation to Carlton House] , who brought good manners and clever conversation. From seven to eight the harp; at eight Mrs. L. and Miss E. arrived, and for the rest of the evening the drawing-room was thus arranged: on the sofa the two ladies, Henry and myself, making the best of it; on the opposite side Fanny and Mr. Haden, in two chairs (I believe, at least, they had two chairs), talking together uninterruptedly. Fancy the scene! And what is to be fancied next? Why that Mr. H. dines here again to-morrow. . . Mr. H. is reading ‘Mansfield Park’ for the first time, and prefers it to P. and P.”