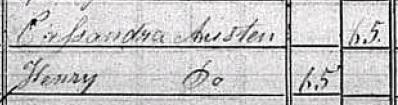

Panorama of Bath from Beechen Cliff, 1824, Harvey Wood

Inquiring Readers, Tony Grant, who lives in London, teaches, and acts as occasional tour guide, has been contributing articles to Jane Austen Today for several months. Recently, Tony and his family traveled to Bath and the West Country. This is one of many posts he has written about his journey. Tony also has his own blog, London Calling.

The Paragon from Travelpod

On Wednesday 6th May 1801 Jane wrote to Cassandra, from a house positioned on a hill half way up a road called, The Paragon, in Bath. It was her uncle and aunt’s, the Leigh Perrots, home. Her aunt was her mother’s sister. Jane and her mother and father had just arrived, just moved in and were getting settled into their rooms.

“ My dear Cassandra,

I have the pleasure of writing from my own room up two pairs of stairs, with everything very comfortable about me. Our journey here was perfectly free from accident or Event; we changed horses at the end of every stage, & paid almost at every turnpike;- we had charming weather, hardly any dust,& were exceedingly agreeable, as we did not speak above once in every three miles.- between Luggershall & Everley we made our grand meal…….”

Jane had arrived in Bath after a journey of about 50 miles from Steventon, her home.

Wood engraving of Steventon Rectory

She sounds excited and thrilled by the new experience for instance she has ,” my own room.” But perhaps she was trying to put a brave face on it, be positive and put the negatives to the back of her mind.

Claire Tomlin reminds us,

“ The decision by Mr and Mrs Austen to leave their home of over thirty years, taking their children with them, came as a complete surprise to her; in effect, a twenty fifth birthday surprise, in December 1800. Not a word had been said to anyone in advance of the decision.”

Jane had spent all her life in Steventon a quiet country village near Basingstoke in Hampshire. She knew the families who lived in the great houses and many were her friends. She knew the villagers of Steventon very well. It was the source of her imagination and she had developed her own intimate writing habits there. Her world , in a sense was turned upside down and she was being wrenched from this intimate, close world that she was comfortable in, to that of a bustling town, but not just any town.

The Bath Medley, the Pump Room, detail on a fan, 1735

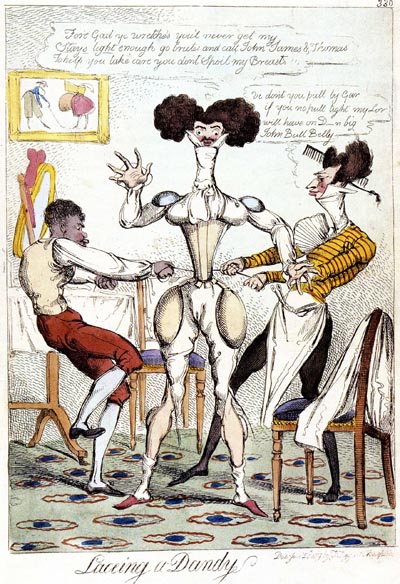

Bath was the centre of Georgian ,”FUN.” Here people came for the medicinal benefits of the waters, dancing, parading in the streets in their finest clothes, drinking tea, and taking rides and walks out into the nearby countryside. It was a place to rest, to be seen and to meet new people. Many families brought their unmarried daughters here to find eligible spouses.

Dancing, Rowlandson, The Comforts of Bath

Bath was a magnet for the wealthy and comfortable middle classes who came and went with the season. It was a fluctuating population. Friendships could be brief. It was a hot house for relationships. Whether The Reverend George Austen had it in mind to find suitors for his two unmarried daughters, as part of his plan, is not certain. Jane however was definitely out of her comfort zone. She was a very astute judge of characters and she would not like much of the ostentatious show of Bath. People who went to Bath for the season behaved differently. Strangers were thrown together in a mix of fun and gaiety. Moral codes were loosened. You get a very strong sense of this in the description of Catherine Morelands first experiences of Bath in Northanger Abbey.

Comforts of Bath, The Pump Room, Rowlandson

To get to Bath from Steventon over the fifty mile journey, Jane took, she passed through many picturesque and beautiful villages and towns. Those places are still there today.

Overton, Andover, Weyhill, Ludgershall, Eveleigh, where the Austens stopped to take tea and rest, Upavon, crossing the River Avon at this point, Conock and Devizes where they probably rested again before the final stretch to Bath. Devizes is a bustling town today, traffic and shoppers, many small businesses, churches and chapels and still many magnificent Georgian buildings. Take away the cars, and dress the people differently and Devizes would still be very familiar to Jane. It still has very much of its Georgian character but it is a modern 21st century town too.Like modern day England, Devizes is a layer cake of history. There are bits from every era and it has and does thrive in all of them.

Strolling through Sydney Gardens

When I went to Bath this time I came in from a slightly different direction to Janes journey there in 1801. I came the south east, travelling from Stonehenge in Wiltshire. This road comes from high up in the hills to the south of Bath and the first sight of the city is from a steep, tree lined, Beckford Road which reaches Bath stretching along next to Sydney Gardens. It was a great pleasure and very exciting to come across, almost immediately on reaching Bath, number 4 Sydney Place, which was one of the houses Jane and her family rented.

Georgian terraced houses along the London Road, Bath

Jane entered Bath by way of the London Road which sweeps in from the east and curves across the top of the bend in the River Avon which borders the southern part of the City of Bath.The London Road leads straight to The Paragon, the road in which her aunt and uncle, The Leigh Perrots, lived and where Jane and her mother and father were to live until they found their own residence. Bath has not expanded in modern times much south of the river partly because of the steep hills there.

Old - Lower - Assembly Rooms

So there is an excited tone in Janes first letter from The Paragon. The excitement doesn’t last. Her aunt and uncle being residents in Bath, they at least know people to introduce Jane to. Unlike Catherine Moreland who meets nobody and knows no one at first. But what terrible people? Or is Jane just having a bout of sour grapes? Within weeks Jane is writing to Cassandra her comments about Bath acquaintances.

Wednesday 13th may 1801 writing to Cassandra

“I cannot anyhow continue to find people agreeable; I respect Mrs Chamberlayne for doing her hair well, but cannot feel a more tender sentiment.”

Mrs Chamberlayne is picked out for more effort. Jane tries to find something in common, tries to see if a new friendship can blossom.

Friday 22nd May 1801

“The friendship between Mrs Chamberlayne & me which you predicted has already taken place, for we shake hands whenever we meet Our grand walk to Weston was again fixed for yesterday & was accomplished in a very striking manner; Everyone of the party declined it under some pretence or other except our two selves, & we therefore had a tete a tete, but that we should equally have had after the first two yards, had half the inhabitants of Bath set off with us.- It would have amused you to see our progress;-we went up by Sion Hill, and returned across the fields,- in climbing a hill Mrs Chamberlayne is very capital; I could with diffuculty keep pace with her- yet would not flinch for the world.- On plain ground I was quite her equal- and so we posted away under a fine hot sun, She without any parasol or any shade to her hat, stopping for nothing ,& crossing the churchyard at Weston with as much expedition as if we were afraid of being buried alive.-After seeing what she is equal to, I cannot help feeling a regard for her.-As to agreeableness, she is much like other people.”

There is something final about this relationship as though it’s not going far, in two phrases, “The friendship between Mrs Chamberlayne & me which you predicted has already taken place,…..” and , “As to agreeableness, she is much like other people.”

Regency Bath

Jane uses the past tense already about the relationship with Mrs Chamberlayne and she finally concludes that she is much like other people. Nothing is going to happen here. Jane was a very guarded person, certainly didn’t suffer fools gladly, gave people a chance and discarded them for their mediocrity. Jane obviously needed something else in a relationship. Already she wasn’t in the mood for Bath.

Candle Snuffer, image Tony Grant

In the same letter she mentions house hunting. They have been looking at houses amongst Green Park Buildings. Green Park Buildings are situated near the river at the bottom of the town. They were obviously prone to flooding.

“ our views on GP building seem all at an end; the observations of the damps still remaining the offices of an house which has only been vacated a week, with reports of discontented families& putrid fevers have given the coup de grace.”

Nowadays the river near Green Park Buildings has high banks to prevent flooding and has been canalised. One of the main car parks, where we actually parked is near there. Also Bath Railway Station and The University of Bath is situated nearby these days.

For all this dire and damning report the Austens did move into Green Park Buildings. It could not have been very pleasant. Perhaps they thought their stay in The Paragon was prolonged enough and anything had to be taken.

Much of Jane’s remaining letters from Bath have some discussion about finding accommodation. The contracts on these houses seem to have been short term. Maybe this was because Bath was a seasonal place. People generally came for short periods of time. If you really wanted to live there permanently you would have to buy. Perhaps the Austens could not afford to do that. It begs the question, did Mr and Mrs Austen really think through their move to Bath carefully enough?

25 Gay Street, image Tony Grant

After Green Park Buildings the next set of letters come from number 25 Gay Street, just a few houses up the hill from The Jane Austen Centre. It is a dental practioners office today. The letters from Gay Street are the last from an address in Bath. However we also know that Jane lived at number 4 Sydney Street, a new house at the time overlooking a grand house which is now the Holburn Museum and its grounds, Sydney Park. This is by far one of the more pleasant situations Jane lived in.

Jane’s father died in a house in Trim Street not far from Queen Square and Gay Street. So another move had had to take place. In five years Jane had lived in at least five different house all providing differing qualities of living.

Side Street, Bath, image by Tony Grant

You can find this reflected in the two novels that concern themselves most with Bath, Persuasion and Northanger Abbey. In Persuasion Anne Elliot finds an old school friend, Mrs Smith, living in poor circumstances.

“Her accommodations were limited to a noisy parlour , and a dark bedroom behind, with no possibility of moving from one to the otherwithiout assistancewhich there was only one servant in the house to affordand she never quitted the house but to be conveyed into the warm bath.”

Mrs Smith’s accommodation was in Westgate Buildings not far from the Pump Room. Mrs Smith’s husband had died leaving her almost penniless but because of her health the warm bath treatment was seen as a cure. Her life was certainly not one of fun and frivolity. It seems, like in any city and town today, in the 18th century, the poor and destitute and the wealthy are not far from each other. Anne Elliot seems to prefer the company of Mrs Smith rather than the fripperies that Bath had to offer. She knows the right people and could have fun if she wanted to. Anne Elliot can see the two sides of Bath.

Side view of Bath Abbey, image Tony Grant

Jane Austen knew Bath extremely well. Throughout Persuasion and Northanger Abbey she houses her characters in real streets and in real buildings, although she does avoid giving us the number of the house in such and such a street. The real owners and occupants might not have liked the notoriety. And today they might not like the notoriety as well. Was there such a thing as litigation in the 18th century? I’m sure there was.

More About the Topic

Cheap Street with hills in the distance, image from Tony Grant

Read Full Post »