French paintings of ladies dressing and at their toilettes provide us with an insight of how dressing rooms were once constructed and used. While we think of dressing as a private affair, William Hogarth demonstrates in his painting, Marriage à-la-mode: The Countess’s Morning Levee, how a woman of means with a large elaborate dressing room would entertain visitors while she was completing her toilette.

Image @Wikipedia

In reality, the toilette became a ritual in 18th century France for the very rich, one that had both intimate and public elements. A maid would groom and sponge bathe her lady in private, but then her mistress would devote hours to having her hair dressed, eating her breakfast from a tray, writing letters, entertaining friends, and picking the clothes she would wear for the day. The wealthier the woman, the more elaborate her morning ritual. As Hogarth showed, the custom of entertaining guests in one’s dressing room was also popular in England. In the image below, a shameless young lady is entertaining her spiritual adviser in her boudoir. His expression is priceless.

The Four Times of Day: Morning, Nicholas Lancret, 1739. Image@National Gallery, London

Wikipedia provides a history of the word “toilet”. The word did not have the same meaning back then as it does today.:

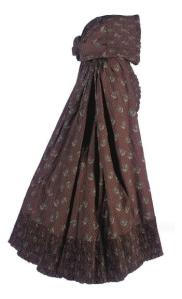

It originally referred to the toile, French for “cloth”, draped over a lady or gentleman’s shoulders while their hair was being dressed, and then (in both French and English) by extension to the various elements, and also the whole complex of operations of hairdressing and body care that centered at a dressing table, also covered by a cloth, on which stood a mirror and various brushes and containers for powder and make-up: this ensemble was also a toilette, as also was the period spent at the table, during which close friends or tradesmen were often received. The English poet Alexander Pope in The Rape of the Lock (1717) described the intricacies of a lady’s preparation:

“And now, unveil’d, the toilet stands display’d

Each silver vase in mystic order laid.”

These various senses are first recorded by the OED (Oxford English Dictionary) in rapid sequence in the later 17th century: the set of “articles required or used in dressing” 1662, the “action or process of dressing” 1681, the cloth on the table 1682, the cloth round the shoulders 1684, the table itself 1695, and the “reception of visitors by a lady during the concluding stages of her toilet” 1703 (also known as a “toilet-call”), but in the sense of a special room the earliest use is 1819, and this does not seem to include a lavatory.

La Toilette, Boucher, 1742. Image@francoisboucher.org

Woman’s Fashions of the 18th Century fully describes the above painting by Boucher, in which the seated woman, probably a courtesan, is tying a garter over her stocking while wearing a short jacket to protect her outfit from particles of applied makeup and the powder on her wig. No visitors invade this intimate scene, which clearly shows a tray with refreshments and a decorative dressing screen behind the chair.

James Gillray portrays the progress of the toilet. Note the wash basin and water urn on the floor.

Women did use their dressing rooms at more intimate and private moments, when one presumed they would be alone. The washing of one’s face, feet and hands was a daily ritual, while bathing one’s entire body was not. Such ablutions were done privately. People would wash in basins. A portable hip bath would be placed in the dressing room if they decided to bathe completely.

Boilly, La Toilette Intime ou la Rose Effeuille. Image @Wikimedia Commons

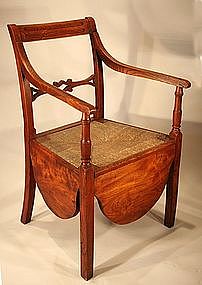

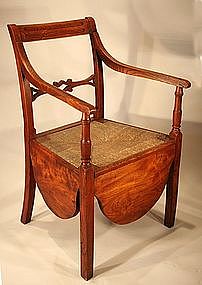

While outhouses were common, the wealthy tended to use elaborate potty chairs (see image below). The French used bidets inside their dressing rooms, as shown in Boilly’s painting above. Invented by the French, their earliest recorded use was in 1710. If one wonders how women in elaborate costumes managed to go to the bathroom, this image by Boucher provides a glimpse. The handling of the bowl and upright posture was possible, for women during that era wore no underdrawers.

18th century Sheraton potty chair

Dressing rooms remained popular for a long time. In Can You Forgive Her?, Lady Glencora invites Alice Vavasor to have tea in her dressing-room, saying “You must be famished, I know. Then you can come down, or if you want to avoid two dressings you can sit over the fire up-stairs till dinner-time.” Alice follows Lady Glencora into the dressing-room, “and there found herself surrounded by an infinitude of feminine luxuries. The prettiest of tables were there;–the easiest of chairs;–the most costly of cabinets;–the quaintest of old china ornaments. It was bright with the gayest colours,–made pleasant to the eye with the binding of many books, having nymphs painted on the ceiling and little Cupids on the doors.” Lady Glencora goes on to explain, “I call it my dressing-room because in that way I can keep people out of it, but I have my brushes and soap in a little closet there, and my clothes,–my clothes are everywhere I suppose, only there are none of them here.”

Dressing room with chamber pot chair, 1765. Image@Morris Jumel House, Manhattan.

Anthony Trollope made an interesting point. During the 1860’s, when his novel was written, wealthy women changed their wardrobes more often for different functions during the day than Regency women. She invites Alice to linger in her dressing room, presumably to rest, read, and drink tea, rather than change into yet another set of clothes to join the company downstairs. Lady Glencora also indicates that the dressing room could also be a refuge away from visitors and prying eyes.

Jane Austen's bedroom. The closet with wash basin and potty sits to the left of the fireplace.

A wealthy couple might have two bedrooms (his and hers) with an adjoining sitting room. Each person would have their own dressing room. Simpler households did not have the luxury of such space. In Chawton Cottage, Jane Austen and her sister, Cassandra, shared one bedroom. Their potty and wash basin where stored in a closet.

Today’s walk in closets with adjoining bathroom most closely approximate the dressing room of yore, although people today do not tend to entertain their visitors in their closets.

Other posts on the topic:

Read Full Post »