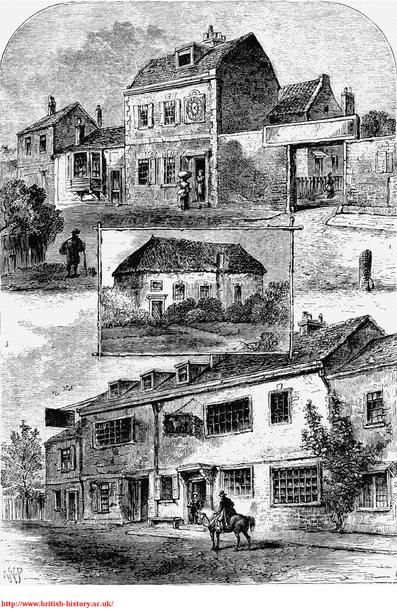

I recently finished reading a charming book by Cora Harrison, I Was Jane Austen’s Best Friend, in which Jane Austen has just reached the age of 15. It is February, 1791, and 16-year-old Jenny Cooper has slipped out of Mrs. Crawley’s boarding school to post a letter to Steventon Rectory warning Rev. and Mrs. Austen that their daughter, Jane, is seriously ill. By doing so, Jenny risks her reputation, for she ventures out alone and unescorted in a rough area of Portsmouth.

I recently finished reading a charming book by Cora Harrison, I Was Jane Austen’s Best Friend, in which Jane Austen has just reached the age of 15. It is February, 1791, and 16-year-old Jenny Cooper has slipped out of Mrs. Crawley’s boarding school to post a letter to Steventon Rectory warning Rev. and Mrs. Austen that their daughter, Jane, is seriously ill. By doing so, Jenny risks her reputation, for she ventures out alone and unescorted in a rough area of Portsmouth.

This scene sets the stage for the rest of the novel, in which young Jenny Cooper chronicles the months she spends with her best friend Jane and the Austens at the rectory. The girls are avid writers: while Jane spins her creative tales, Jenny describes their routine days in her journal. And what days they were! Jenny observes Jane’s family and friends minutely: her gentle father and stern mother; her charming favorite brother, Henry, and the mentally challenged George, who lived with another family; Cassandra’s love for Tom Fowle; exotic cousin Eliza; the well-dressed Bigg sisters; and other vivid portraits of the people who inhabited Jane’s and Jenny’s world.

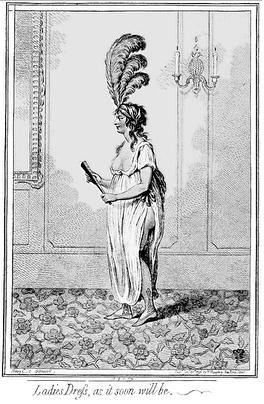

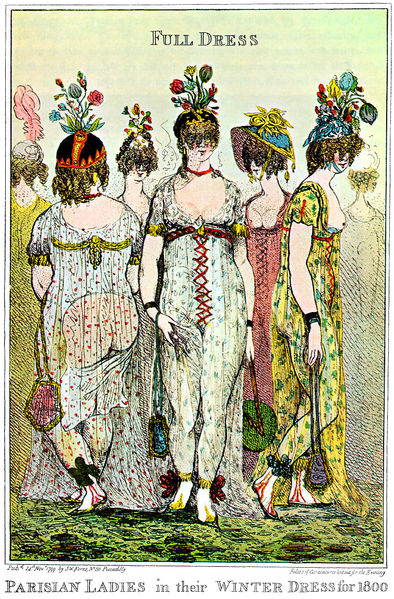

The scenes are culled from actual events in Jane’s life and from letters that others wrote about her (for none of her letters from that time have survived). As teenagers are wont to do, Jenny and Jane dream of romantic encounters and parties and balls, engage in outdoor activities, and while away their time reading and writing and play-acting, or wishing for pretty gowns.

The scene in which a pinch-penny Mrs. Austen must decide which color muslin would look best for ball gowns for all three girls (Cassandra, Jane and Jenny) is priceless, and the descriptions of tender romance between Cassandra and young Tom are heartbreaking to those who know he will die before they can be married. Tom LeFroy makes a suitably short appearance, and Jenny meets handsome Captain Thomas Williams, who in real life became engaged to her within three weeks of their first meeting, and whom she later married before her own untimely death.

Jenny witnessed Jane writing constantly and being inspired by the people she observed. For example, Jenny’s shrill sister-in-law, Augusta, becomes the prototype for Mrs. Elton and Mr. Collins is somewhat inspired by Jenny’s preachy brother.

While I found the book a delight, not everyone has been thrilled with its purchase. The American cover of I Was Jane Austen’s Best Friend is a bit mature for a novel that targets young girls of eleven or so, but it explains the reason why so many older readers are buying the book.

This is what a high school reviewer had to say about the U.S. cover: “… if you plan on buying [the book] at any time soon, make sure to check out the U.K. version… the cover art is so much cuter!” In fact, the U.K. cover (below) enjoyed the author’s full approval, and was drawn by Susan Hellard, the artist responsible for the charming illustrations displayed in this post and that are sprinkled throughout the book.

Page from the book, in which Jane describes some of her siblings. The style of writing is aimed at a very young audience. Drawings @Susan Hellard.

In writing this novel, Cora Harrison has kept her very young audience in mind. As you can see from the sample page above, the sentences are short and written in plain English, speech patterns and terms from the 18th century are kept to a minimum, the romance is sweet, and the story is written from a young lady’s point of view. While Ms.Harrison hoped that this book would introduce Jane Austen to very young readers, she also envisioned that mothers and grandmothers would enjoy reading the novel as well.

I have gone into great detail about the author’s intentions for a reason. Reviews of this book, while largely favorable, are varied. Lower rankings come largely from disappointed adult readers who expected a mature romance and a “more interesting plot.” But as the author wrote to me: “I didn’t want to do an in-depth analysis of love. I wanted to do a fun book, romantic in an old-fashioned style.”

Purists have also decried the changes in facts, dates, and characters, but isn’t it the novelist’s prerogative to change historical facts in order to move the plot forward? Besides, Ms. Harrison made her reasons for these changes clear in her Author’s Note in back of the book, which should have been placed as a Foreword. I also think that annotated notes for juvenile readers (such as those included for book clubs), would help adults explain some of the more obscure facts about the Georgian period to their children and place events in the novel in context.

Be that as it may, I rarely read review books from cover to cover, but I kept reading this one until I was finished (and then wished I had a daughter to give it to). This is a sweet book, filled with useful details about life in England 200 years ago. Ms. Harrison’s conjectures on how the Austens lived and interacted with each other is based on the letters and information about Jane that survived. After reading these pages, it is clear that Cora Harrison wrote her novel as an homage to Jane Austen. She also is an author with a mission. “As a teacher I am realistic enough to know that girls won’t automatically read Jane Austen unless their interest is awakened and I hoped to do that…”

Be that as it may, I rarely read review books from cover to cover, but I kept reading this one until I was finished (and then wished I had a daughter to give it to). This is a sweet book, filled with useful details about life in England 200 years ago. Ms. Harrison’s conjectures on how the Austens lived and interacted with each other is based on the letters and information about Jane that survived. After reading these pages, it is clear that Cora Harrison wrote her novel as an homage to Jane Austen. She also is an author with a mission. “As a teacher I am realistic enough to know that girls won’t automatically read Jane Austen unless their interest is awakened and I hoped to do that…”

More on the topic: