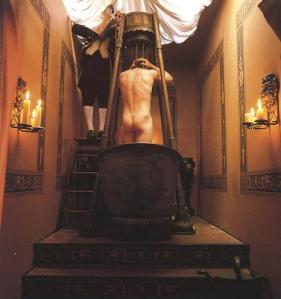

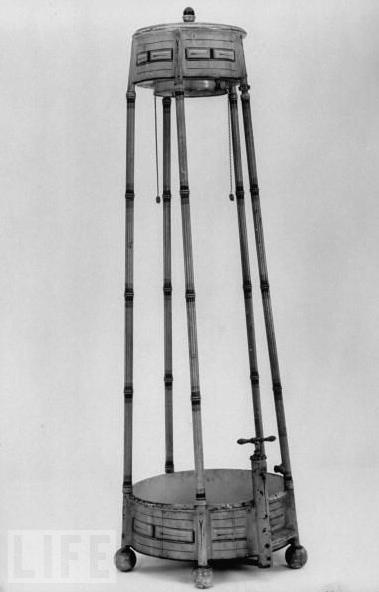

Copyright (c) Jane Austen’s World. Take a good look at this contraption. Life Magazine gave it the following description:

A treasury of old tubbery, Regency shower 12 feet high was a fancy bathing apparatus in England around 1810, pump lifted water from tank at bottom through pipe to top tank, water could be used over and over again.” – Life Magazine image

Readers familiar with the Regency era know that attitudes towards bathing and hygiene were on the cusp of change. In the early 18th century, a person might wash their face and hands daily, but at the most they would bathe every few weeks or months. Towards the end of the century, cleanliness was no longer regarded as frivolous by a growing number of people. Beau Brummel was a particular proponent of bathing and his affectation for cleanliness became the dandy’s creed. Others began to associate bathing with good health.

Washing made a comeback in the later 18th century. The age of revolution and romanticism valued simplicity and naturalness, and water – in the form of mountain torrents and medicinal springs – became fashionable. Rousseau recommended bathing children in ice-cold water, winter and summer, and a sophisticated clientele sought to relieve its frayed nerves and overtaxed digestions by taking the waters at spas. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, who invented the phrase “Cleanliness is next to godliness”, wrote a manual claiming that cold baths had been known to cure blind-ness and leprosy, as well as “hysterick cholik” in ladies. – Review of Clean, An Unsanitized History of Washing

The Americans echoed the British attitude towards cleanliness:

Until the last third of the 18th century, bathing practices were not clearly defined or categorized. The perceived effects on the body of the cold and warm bath were debated regularly in prescriptive literature, as were reasons for bathing in the first place. Motives for bathing changed somewhat over time, and different methods had specific connotations: did one bathe for pleasure, as a restorative of good health, for leisure and/or hot weather refreshment, as a luxurious display, or for actual, bodily cleanliness? Whatever the motivation, it was then up to the bather to decide whether she or he adhered to the cold or warm water method. – Bathing, Monticello.org

If a person opted to take a shower, the effect was at first quite bracing, for only cold water was used with this fairly new contraption, invented in 1767)by William Feetham. In the image from Regency House Party, a servant is seen pouring water into the basin, but Feetham’s patented invention included a pump that forced the water to the upper basin and a chain that was pulled by the bather to pour water over himself. The advantage was that less water was used in bathing (A typical bath tub would require from 6-8 buckets of heated water to be carried from the nearest water source and up several flights of stairs). The early shower system’s disadvantage was clear: the same water would be reused during the course of the shower. Not only did one reuse dirty water, but one felt quite cold during the process.

When the temperature of a bed-room ranges below the freezing-point, there is no inducement . . . to waste any unnecessary time in washing,” wrote Charles Francis Adams, grandson of President John Quincy Adams and brother of historian Henry Adams. To Bathe or Not to Bathe

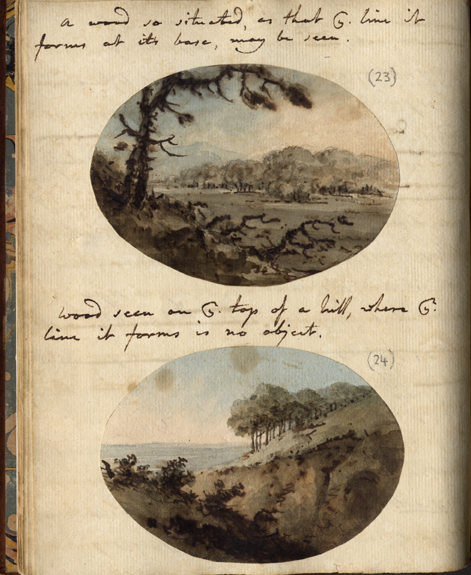

The elaborate bath house at Wimpole Hall, Cambridgeshire, with the shower made by Alexander Boyd of New Bond Street (See their mark below).

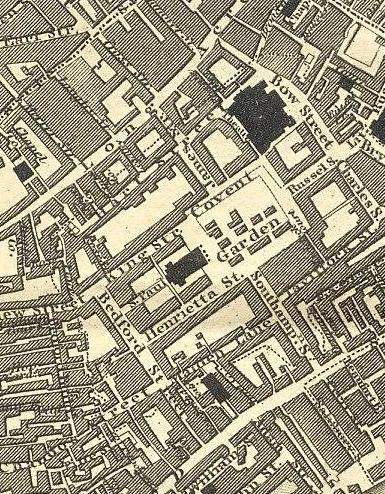

The bath house at Wimpole Hall was unusual for its day. Around 1792, Sir John Soane designed the plunge pool for the 3rd Earl of Hardwicke. The pool held 2,199 gallons of water that was heated by a boiler below it in the basement.

The 10 – 12 ft tall metal supports, or poles, of these showers were painted to resemble bamboo wood and even offered a shower curtain for privacy. To protect their hair, bathers wore a conical hat made out of oil cloth.

Until plumbing with warm water was introduced inside the bathroom, the use of shower baths remained rare. Towards the middle of the 19th century, attitudes began to change.

Plumbers began to introduce indoor plumbing, and inventors experimented with perfecting showering tools and pumping in hot water. Improvements in showering equipment was continuous, as the patent given to William Feetham (below) in 1822 attests: To William Feetham of Ludgate Hill, in the City of London, Stove grate Maker and Furnishing Iron monger, for his Invention of certain Improvements on Shower Baths, Sealed June 13 1822.

The intention of these improvements is to enable the patient, who is using the bath to regulate the flow of water, and thereby to soften the shower according as inclination or circumstances may require. This object is effected by two contrivances: the first is an adjustable stop, which may be set so as to prevent the cock from turning beyond any certain distance, so as to limit the opening of the water way to any required discharge; the second is a division of the perforated box or strainer into several chambers by two or more circular concentric partitions, by which limited quantities of water let out from the cistern above are necessarily confined to limited portions of the surface of the strainer … Read more about the patent in The London Journal of Arts and Sciences, Vol. 5, Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, 1823, p284-6.

The Patentee states: “I do not claim, or intend hereby to claim, as my invention any of the parts which may be already in use, but I do claim the means of regulating the flow of the water from the cock of a shower bath, and also the method of extending, or contracting within central limits, the shower of water at pleasure.”

In December, 1822, Mr. Feetham was granted the patent for the following improvements:

By the 1870’s, even middle class houses began to have hot water pumped in, for the increased rents the landlords were able to command for houses with hot water made it worthwhile for them to invest in plumbing. Sponge baths were still recommended for “invigorating the system,” and as late as 1875 The Ladies Everyday Book cautioned that it was a great mistake to make a bath a regular event.

Godey’s Ladys Book, a popular ladies magazine in the U.S., reflected the changes in attitude towards bathing (as does John Leech’s 1851 cartoon):

Godey’s, June 1855:

The shower -bath has the merit of being attainable by most persons, at any rate when at home, and is now made in various portable shapes. The shock communicated by it is not always safe; but it is powerful in its action, and the first disagreeable sensation after pulling the fatal string is succeeded by a delicious feeling of renewed health and vitality. The dose of water is generally made too large; and, by diminishing this, and wearing one of the high-peaked or extinguisher caps now in use, to break the fall of the descending torrent upon the head, the terrors of the shower-bath may be abated, while the beneficial effects are retained.

Godey’s, March 1858:

The Shower Bath, whether of fresh or salt water, whether quite cold or tepid, is a valuable agent in the treatment of many nervous affections; it will suit some whom the general bath will not. It is well for persons of weak habit, or who suffer from the head, to have a thin layer of warm water put in the bottom of the shower bath before getting in. Useful hand shower baths are now manufactured for children.

Domestic Sanitary Regulation, John Leech 1851. In this scene, the shower is installed in the kitchen. The children are wearing the conical caps to protect their hair as they wait their turn wearing blankets, jackets or robes.

More on the topic: