Over a century ago, Douglas Jerrold asked:

Over a century ago, Douglas Jerrold asked:

Is there a more helpless, a more forlorn and unprotected, creature than, in nine cases out of ten, the Dress Maker’s Girl – the Daily Sempstress; pushed prematurely from the parental hearth, or rather no hearth, to win her miserable crust by aching fingers?

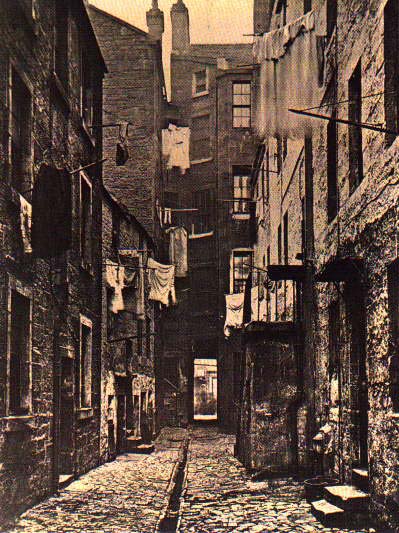

Imagine that it is the Season in London and young ladies and their mamas are ordering dresses by the dozens for balls and visits. In an age when all sewing and embroidery were done by hand, when lighting was poor and wages were so low that they barely paid for room and board, pity the poor seamstress hunched over her sewing assignments, racing against time to meet a series of deadlines that seem endless, and complying with the exacting standards of a boss and clients who cared not a whit for her comfort.

Fingers numb, backs aching, eyes straining to focus on mind numbingly repetitive work meant that burning the midnight oil was no mere phrase. For embroiderers who continued to work well past dusk, lamps were devised that amplified light. Those who sat closest to its source benefited the most. The poor women who sat in the outer circle scarcely benefited from the amplification of lacemaker lamps:

“The three legged stool (candle-block, candle-stool or pole-board are alternative names) upon which the candle and the water filled “magnifying” flasks are fitted, is placed in the middle of the room. The laceworkers then arrange themselves around the light in an orderly manner that allows each person to have at least some of the light.  The best lacemakers use the highest stools and are nearest the light source. They have what is known as the “first-light” then the graded workers arrange themselves according to ability to have the “second-light” and the “third light”. Whiting tells us that in this way 18 lacemakers can be accommodated around the candle-stool.

The best lacemakers use the highest stools and are nearest the light source. They have what is known as the “first-light” then the graded workers arrange themselves according to ability to have the “second-light” and the “third light”. Whiting tells us that in this way 18 lacemakers can be accommodated around the candle-stool.

From my own experiments with this form of lighting, I find it hard to understand how any maker who was in the third light, or even the second light come to that, could make lace from that single source of illumination!” – Brian Lemin

Mr. Jerrod’s prose is purply, like much of the writing during the Victorian era, but one gets the gist of what life must have been like for a lowly little seamstress toiling in a garret room with other seamstresses. The hours were long, and sometimes unpredictable:

Our little Dress Maker has arrived at the work room, After two or three hours she takes her bread and butter and warm adulterated water denominated tea. Breakfast hurriedly over, she works under the rigid scrutinising eye of a task mistress some four hours more, and then proceeds to the important work of dinner. A scanty slice of meat, perhaps an egg, is produced from her basket; she dines and sews again till five. Then comes again the fluid of the morning and again the needle until eight. Hark, yes, that’s eight now striking. “Thank heaven,” thinks our heroine, as she rises to put by her work, the task for the day is done.

At this moment a thundering knock is heard at the door: — The Duchess of Daffodils must have her robe by four to morrow!

Again the Dress Maker’s apprentice is made to take her place — again, she resumes her thread and needle, and perhaps the clock is “beating one”, as she again, jaded and half dead with work, creeps to her lodging, and goes to bed, still haunted with the thought that as the work “is very back”, she must be up by five to-morrow.

Pity the woman who was born to luxury who lost a father before she was comfortably married and, because of his debts or other hardship, had to work for a living. Preferred jobs included governess, chaperone, or a ladies companion, but they often led to a woman living a life of limbo. Neither servant nor family member, they spent lonely lives of servitude, fitting in nowhere. If a woman could not obtain employment in those positions, she could always turn to sewing as either an independent dressmaker or seamstress. Jane Austen’s friend, Mary Lamb, made her living as a mantua maker, sewing garments for women and men in her own home, and taking up mending. In Persuasion, Mrs. Smith knitted small souvenir objects, which Nurse Rooke sold for her.

Dress maker in 1840

These women, accustomed to luxury in their earlier years, were exposed to sumptuous homes and surroundings as they visited their clients for fittings. Yet their earnings of twelve or fifteen shillings per week (1840 quote) were hardly sufficient to provide for adequate food and lodging. Independent dressmakers had to look neat and presentable, yet they could barely afford their upkeep. Her life could even turn for the worse if she never married. She would then be fated to grow old in a world that was harsh for single women. Barely able to scrape a living together while she was young and healthy, she was fated to lose her excellent eyesight due to the strain of her work.

The Children’s Employment Commission in 1842 estimated that there were some 1000 millinery and dressmaking businesses in London (millinery is here equivalent to dressmaking; the word was not confined to hat makers until the end of the century), and Nicola Phillips estimates that 95 per cent of these were run by women. It is a common mistake to confuse one needlewoman with another, but as Kay points out, ‘the businesswoman milliner is a different creature to the jobbing sempstress’: one designed and made or had made individual garments; the other worked by the piece, either for a milliner or stitching pre-cut ready-made clothes – (The Foundations of Female Entrepreneurship, Alison Kay, p. 48).

Dressmaker shop in 1775. Image from Regency England by Yvonne Forsling

Owning a shop was no guarantee of economic stability, for many wealthy women failed to pay their bills on time, if at all. In the 18th century, the enterprising Hannah Glasse ran a dressmaker’s shop in London with her daughter, which eventually went bankrupt. She went on to write one of the most popular cookbooks of her era, but in this venture she too lost money.

As the century progressed and with the advent of the sewing machine, life did not automatically become easier for seamstresses and dressmakers, who still worked long hours in cramped conditions, their backs bent over sewing machines in factories and piece work shops. Clothing had become more affordable. The rising middle class was purchasing more items than ever, and etiquette dictated that wealthy ladies were required to change their clothes for different functions throughout the day. Thus demand for new and fashionable clothes remained high.

Bottom image from Regency England

More reading on the topic:

Read Full Post »

The best lacemakers use the highest stools and are nearest the light source. They have what is known as the “first-light” then the graded workers arrange themselves according to ability to have the “second-light” and the “third light”. Whiting tells us that in this way 18 lacemakers can be accommodated around the candle-stool.

The best lacemakers use the highest stools and are nearest the light source. They have what is known as the “first-light” then the graded workers arrange themselves according to ability to have the “second-light” and the “third light”. Whiting tells us that in this way 18 lacemakers can be accommodated around the candle-stool.