Several years ago I wrote a post on Regency Hairstyles and their Accessories. This series of images starts much earlier than the Regency. Jane Austen, who was born in 1775, would have been familiar with the hairstyles depicted here up to 1817, the year of her death. Her mother and aunts would have worn longer curls and powdered hair in her childhood. As teenagers and young women just coming on the marriage mart, she and Cassandra would have worn their hair much like the women in the 1790s.

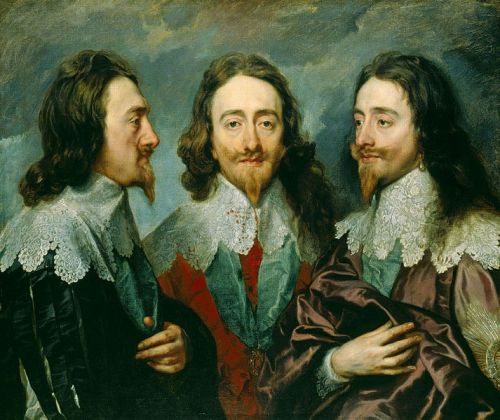

As can be seen from the paintings, hairdos were elaborate in the 1780s and 1790s. Wigs made from real human hair were often used to build up elaborate hair structures. These confections took so many hours to create that a woman would wear them for days on end, protecting the hairdo at night.

Wigs and hair were covered with hair powder made of starch (potato or rice flour, not wheat flour). Oily pomades applied to the hair allowed the powder to stick and fragrant oils masked odors.

Hairdos became increasingly less elaborate and by the end of the 18th century women began to look to antiquity for role models. (Regency Hairstyles and their Accessories.) A woman’s natural hair color was allowed to shine. More often than not, women tied back their hair in chignons that exposed the neck. In some instances, hairdos were cut boyishly short. Lady Caroline Lamb cut her hair short, as did the two girls shown in 1810.

I cannot anyhow continue to find people agreeable; I respect Mrs. Chamberlayne for doing her hair well, but cannot feel a more tender sentiment – Jane Austen, 1801

Even when wearing hats, curls were coaxed out to frame the face. The woman below right with straight hair pulled back into a severe chignon wears curls in front of her ears. Curling tongs were very much in use during this era, as were paper and cloth curlers worn at night.

She looks very well, and her hair is done up with an elegance to do credit to any education.” – Jane Austen, 1813

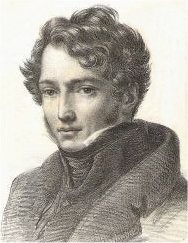

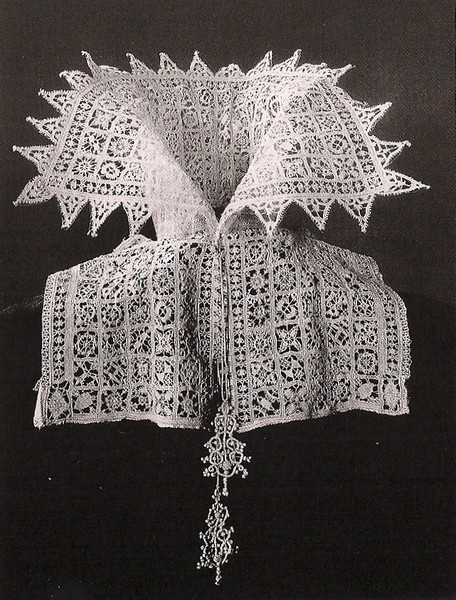

Jane Austen wore caps over her light brown hair, but allowed curls to peep out from under them. I imagine that her nieces at a ball looked much like the young miss at top left in 1813. Hairdos became slowly more elaborate as dresses as dresses were embellished with frills, lace, and other furbelows. Jane would not have recognized the more elaborately decorated dresses and stylized hairstyles of the mid-1820s and 1830s, in which natural flowing lines were taken over by elaborately ruffled collars and skirt hems. Had she lived, she might even have made a joke at the expense of ladies who wore the popular but elaborately built-up hairstyles at the crown, with ringlets cascading down the sides, and flowers and feathers arranged artfully into the curls. (Modes des Paris image.)

More on the topic

To see a Regency timeline of headresses and hairstyles for Regency evenings and their descriptions, click here.