Copyright @Jane Austen’s World. Post written by Tony Grant, London Calling.

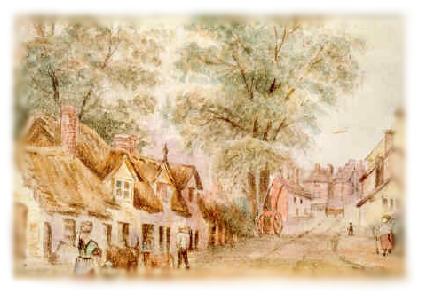

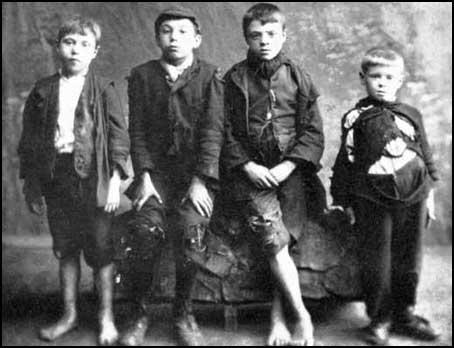

John Clare (1793-1864) was born at Helpston, a village in Northamptonshire on July 13th 1793. Jane Austen was 18 years old and living in the south in an equally rural setting of the parsonage at Steventon, Hampshire. Her family and life was very different to John Clare’s. His father was a farm labourer, a fairground wrestler and a ballad singer. The ballad singing was John’s first introduction to verse, rhythm and rhyme.

John Clare (1793-1864) was born at Helpston, a village in Northamptonshire on July 13th 1793. Jane Austen was 18 years old and living in the south in an equally rural setting of the parsonage at Steventon, Hampshire. Her family and life was very different to John Clare’s. His father was a farm labourer, a fairground wrestler and a ballad singer. The ballad singing was John’s first introduction to verse, rhythm and rhyme.

John Clare was at first educated at a dame school in his native village between 1798 and 1800. Then he went to Glinton school in the next village.

He had a need to write poetry and his first poems were based on his father’s songs. People said of him at the time and nowadays that he was a self-taught poet. It’s difficult to imagine anybody being taught to be a poet. John Clare could hear the rhythms and rhymes in his father’s songs and he did read quite extensively. He was able to think in rhythms and find the right words to say what he wanted by writing poetry. He was sensitive to the sounds and meanings of words and was able to put them together. Great writers don’t learn to be great writers. They have certain skills but the rest is innate. They can hear and find things in words that is very difficult for the rest of us. Otherwise we could all do it. People have struggled to explain the genius of Shakespeare and perhaps Jane Austen. They didn’t come from the aristocracy or were particularly well educated. It was part of their inner selves. That can be the only explanation. Great lawyers or accountants or architects are taught the knowledge they need and some skills but something innate can only make them great.

John Clare’s father became rheumatic and couldn’t work in the fields and so John had to take his place so the family could eat. He worked as a horse boy, a ploughboy and then became a gardener at Burley House. In 1812 he joined the local militia returning home 18 months later.

When he returned he took up lime burning. Lime was very useful for building purposes. It was and is a necessary ingredient for cement and concrete. It can also be spread on fields to keep pests down.

In Casterton, a village nearby, he met Martha Turner. She became his wife and they had eight children together.

John Clare’s first book of poems was called “Poems Descriptive of Rural Life.” This was published in 1820 by Hessey and Taylor who were Keats publisher. The volume ran to four editions and Clare began to become famous in London literary circles. They called him, the, “peasant poet,” a rather derogatory title in many ways. In 1821 he published “The Village Minstrel,” and in 1827 The Shepherds Calendar,” came out. The success of his first volume, which was obviously a curio, eluded these following books. In 1835, “The Rural Muse,” was produced and hardly sold at all. John Clare and his family had no money and were virtually destitute.

In 1837 John Clare was admitted to Matthew Allen’s private asylum of High Beech in Epping Forest. He was there for four years. He had begun to have delusions. He thought he was Shakespeare for a while. His family couldn’t cope with him. The mental strain of being torn between two worlds was destroying him. After four years he was discharged and had to walk the eighty miles home, which took him three days. He ate grass along the way. When he got home he wrote two long poems based on Byron’s poems Don Juan and Childe Harold.These two poems described his state of mind. Again in December 1841 he was certified insane by two doctors. He was admitted to St Andrew’s County Lunatic Asylum in Northampton where he was treated well. He was able to continue writing poetry. He died there in 1864.

The Skylark

THE rolls and harrows lie at rest beside

The battered road; and spreading far and wide

Above the russet clods, the corn is seen

Sprouting its spiry points of tender green,

Where squats the hare, to terrors wide awake,

Like some brown clod the harrows failed to break.

Opening their golden caskets to the sun,

The buttercups make schoolboys eager run,

To see who shall be first to pluck the prize–

Up from their hurry, see, the skylark flies,

And o’er her half-formed nest, with happy wings

Winnows the air, till in the cloud she sings,

Then hangs a dust-spot in the sunny skies,

And drops, and drops, till in her nest she lies,

Which they unheeded passed–not dreaming then

That birds which flew so high would drop again

To nests upon the ground, which anything

May come at to destroy. Had they the wing

Like such a bird, themselves would be too proud,

And build on nothing but a passing cloud!

As free from danger as the heavens are free

From pain and toil, there would they build and be,

And sail about the world to scenes unheard

Of and unseen–Oh, were they but a bird!

So think they, while they listen to its song,

And smile and fancy and so pass along;

While its low nest, moist with the dews of morn,

Lies safely, with the leveret, in the corn.– John Clare

John Clare often wrote in Iambic pentameter, that most used metre in the English language. Shakespeare and Milton and many poets since have found iambic pentameter the best form to use. It is a ten-syllable line with pared, soft and strong beat pulses. It’s like an inner natural force. It is the most natural rhythm pattern to use because it is close to a conversational style; it’s like our heartbeat and our breathing patterns. It is most apt for conveying every sort of meaning in the English Language. It’s easy and smooth and a real joy to say.

John Clare moves straight into this perfect rhythm in the first two lines of The Skylark with these rhyming couplets.

The rolls and harrows lie at rest beside

The battered road: and spreading far and wide”

The iambic pentameter mesmerises us, carries us along, and Clare enters right into the detail of the countryside with “rolls,” “harrows” and “the battered road.” We are there immediately with him on his walk or ramble about his village.

In this poem, John Clare shows his detailed knowledge of the countryside where he lives and his knowledge about country practices and farming equipment. “Rolls and harrows lie at rest,” “ the battered road,” presumably cut deep and rutted by cartwheels are there for him to see. He describes the colour of the clods of clay, a russet colour, and we learn the season when the events of this poem happen, in his description of the growing corn, “sprouting spiry points of tender green.” It’s the time of year the buttercups are, “ opening their golden caskets to the sun.”

The introduction of humans, in Clare’s poetry, always brings foreboding, fear and the possibility of danger and destruction. In the Skylark “schoolboys eager run, to see who shall be first to pluck the prize.” The boys are not there to admire and be sensitive to nature they want to, “pluck,” it, tear it from it’s place and use it for their own fun and amusement. Are they, the boys, the, “anything,” that, “may come at to destroy?”

Clare shows his closeness and affinity with nature and the world of the countryside with words and phrases such as,

…harrows lie at rest,”

“Where squats the hare, to

terrors wide awake,”“…the skylark flies,

And oe’r her half formed nest, with happy wings

Winnows the air, till in the cloud she sings.”

We are so used to using the word, sings, to describe the sounds a bird makes. Clare has used, in this poem, words to describe country objects and nature; rest, terror, winnows and happy. This is personification. It shows his relationship, his emotional attachment to nature and wild animals. He is part of it and it is part of him.

There is a very powerful section in the poem which describes a certain fear and dislocation in the life of the skylark which the schoolboys create.

Clare describes the skylark suddenly and abruptly flying high to distract them from it’s weak, fragile and vulnerable nest on the ground.

The line starts abruptly:

Up from their hurry, see, the

Skylark flies,

And oe’r her half formed nest, with happy wings

Winnows the air, till in the cloud she sings

Then hangs a dust spot in the sunny skies

And drops, and drops, till in her nest she lies,”

The boys have passed by unaware, and the skylark feels safe to return to her nest and probably her eggs or new laid chicks. She has flown high and put on a happy and joyous show, an act, a false hood, all the time terrified about her nest being discovered. Just as suddenly she drops back down to the nest when the coast is clear. It’s a sudden dramatic,reversal and change of positions.

The description of the skylark being, “a dust spot,” adds to this sense of dislocation. I thought it a strange description of the skylark high in the sky. In a literal sense the skylark might look like a dark spot against the bright blue spring sky. However, a dust spot is dirt that needs to be removed, swept away. It’s out of place. The beauty of the skylark reduced to something dirty. This description has a strange resonance. Why should Clare think of the skylark as a piece of dirt?

To relieve us from all this dire, stark reality, Clare, describes at the end of the poem his idea of perfection. His thoughts are about the schoolboys but this is Clare’s hope. It is sad to think that freedom for Clare can only be in death and the hope of heaven. Only there can the skylark, it’s, “low nest, moist with the dew of morn,” be safe.

Like such a bird themselves

Would be too proudAnd build on nothing but a passing cloud!

As free from danger as the heavens are free

From pain and toil, there would they build and be.”

It is very easy to compare the events in this poem with Clare’s own life and perhaps his feelings about himself. Is he the skylark torn between heaven and earth, the heights of the literary world where many regarded him as a curio, a country yokel, a,”dust spot?” Is the skylark’s vulnerable nest his own vulnerable family and fragile existence back home in his Northamptonshire village?