Biblical passages in workhouses reminded the poor how lucky they were.

There’s nothing romantic about PBS Masterpiece Classic’s excellent 2008 adaptation of Charles Dickens’ classic, Oliver Twist. Those of us who hold warm and fuzzy memories of the musical – Oliver! – should put those singing and dancing images out of our minds. This film version depicts the seamy side of Victorian England that Dickens intended – purists will like it for staying true to the author’s gritty vision, and dislike it for the many changes in the plot, as with the character of Rose Maylie.

Oliver lost his mother within hours of his birth and began a twisted start.

Oliver’s twisted start began not unlike the many orphans of unmarried mothers for whom charity was the only way to survive. In 1848, reformer Lord Ashley referred to the more than thirty thousand children living on the streets as, “naked, filthy, roaming, lawless, and deserted children.” They had no recourse but to live in workhouses, large industrial factories that needed a labor force.

Badly treated workhouse boy.

Back in the mid-19th century workhouses were no better than concentration camps. Conditions were made purposefully harsh to discourage the destitute from asking for help. Those unlucky enough to qualify were given just enough calories to stay alive for the harsh labor they were forced to perform breaking stones or picking oakum*. In addition to the brutal conditions, parents were separated from their children, and wives were separated from their husbands to prevent more breeding.

William Miller as Oliver Twist

In 1834 the average age of death for a person in industrial cities like Leeds and Manchester was nineteen. Almost 1/3 of children had lost at least one parent by the age of 15. The odds that a young child would be orphaned was around 8%.** Such was the world that Charles Dickens grew up in. The child of a debtor and forced into labor in a workhouse at the age of 12, he managed to escape a life of relentless poverty to become one of the most popular and successful authors of his time.

The Board of Guardians eat lavishly while showing Oliver no compassion.

Oliver Twist experienced the horrors of the workhouse from birth. Formerly known as almshouses, these places were supervised by a Board of Guardians, local officials whose aim was to keep the poor out of the way of the middle and upper classes. As in the movie, they treated the poor with complete disdain.

Noah (Adam Gillen) taunts Oliver.

Class was relative. Noah Claypole, who made coffins for Mr. Sowerberry, felt superior to Oliver because he had parents while Oliver did not, and Noah taunted him mercilessly.

Oliver's view of the Sowerberrys, Mr. Bumble, Noah, and Charlotte just before his hair raising escape from the undertaker

The workhouse was administered by unpaid bureaucrats, headed by the Beadle, an elected official. These civil servants treated workhouse residents with scorn and cruelty, reminding them with Biblical passages how lucky they were (“Blessed are the poor…”). The workhouse staff received a somewhat better class of lodging and food for their efforts. – Down and Out in Victorian London

After his escape, Oliver walks to London 70 miles away.

During his journey he spots a carriage that carries the mysterious Mr. Monk, who is searching for him.

London streets are filled with noise and the clatter of carriages.

The lanes are narrow and crowded.

Oliver meetshis first friendly Londoner, the Artful Dodger (Adam Arnold)

For an orphan like Oliver or a woman without family or husband like Nancy, Victorian London was as equally harsh an environment as the workhouse. Newly arrived in town, the Artful Dodger is the only friendly face Oliver sees.

Sophie Okonedo as Nancy

Nancy, a thief and prostitute, had worked for Fagin since the age of 12. She’s one of the few conflicted characters in Dickens’ plot, someone who is neither totally evil, like Sikes or Fagin, or totally good, like Oliver or Rose. Talented actress Sophie Okonedo plays Nancy – the prostitute and thief with a heart of gold – without sentimentality. Although Nancy was a white woman in the novel, black servants were common in Britain, and it’s not a far stretch to imagine that illegitimate mulatto offspring would be forced to make their own way in the world.

Fagin (Timothy Spall) might seem like a nicer character than the Beadle, but he represents oppression of a different kind.

Fagin, played with relish by Timothy Spall, trained his boys as pickpockets in “foul’d and frosty dens, where vice is closely packed and lacks the room to turn.” Bill Sikes – evil and completely merciless as written by Dickens and played by Tom Hardy – was probably a product of the London slums or workhouse.

As described by Dickens, Bill Sikes (Tom Hardy) was a violent man and dog beater who terrorized those around him.

The scene in which young Oliver was sentenced to the gallows was entirely believable. Punishments were uneven and unbelievably harsh. Children as young as twelve were sentenced to death or sent to the penal colony in Australia for minor crimes like pickpocketing, stealing a penny’s worth of paint, or being found in the company of gypsies.

Oliver walks 70 miles to London.

The director of the film, Coky Giedroyc, takes advantage of setting and color to depict Oliver’s world. The workhouse is bleak and gray and the cinematic colors remains so when Oliver works for Mr. Sowerberry, the undertaker. The only bucolic scene is shot during Oliver’s long journey on foot to London, and even then it rains more often than not. London looks and feels crowded and claustrophobic as Oliver walks to the East End. When he enters Fagin’s den, surrounded by colorfully clad boys and stolen scarves, his world brightens, though it remains hemmed in.

Food and colorful scarves in Fagin's lair.

Oliver wakes up in Mr. Brownlow’s house after being rescued from the gallows and his world brightens even more. Light floods over him and Rose and Mrs. Bedwin as they tenderly take care of him. This bright interlude in which Oliver gets a glimpse of another world is short lived. Before long he is plucked away from his sanctuary by Sikes and Fagin, who fear the young boy might reveal their names, location, and criminal operations.

Oliver mistakenly thinks he's died when he wakes up and sees Rose's (Morven Christie) gentle but concerned face.

Written as a serialized novel, Oliver Twist is filled with colorful characters, unsuspected plot twists, and suspense, which translate well into film. The result is a remarkably modern plot that has the feel of a detective story.

The Artful Dodger is always on the make.

Everyone was discussing Oliver Twist, from the newly crowned teenage Queen Victoria (who said she disapproved of the novel for younger readers, but read on herself anyway) to Prime Minister Lord Melbourne (“…all about workhouses and coffin makers and pickpockets… I don’t like that low and debasing view of mankind”) to those who could never afford to buy the novel whole, but who could readily identify with the reality it described. All England found itself caught up in the tale of the lonely and mysterious orphan at the mercy of the parish welfare system. – The Rise of the Killer Serial

Mr. Brownlow (Edward Fox).

Mr. Brownlow, whose pocket was picked by the Artful Dodger, turns out to be Oliver’s grandfather. He gives Oliver shelter in his home after testifying on the boy’s behalf and saving him from the gallows. Only the reader/viewer knows early on about this coincidence. Rose Maylie is now Mr. Brownlow’s ward and lives with him – a plot change Dickensian purists will dislike. Edward, his grandson and Oliver’s half brother, walks a fine line between pretending concern over finding out what happened to Agnes, Oliver’s mother, and ordering his brother’s murder. Julian Rhind-Tutt plays Edward (Mr. Monk) with just the right amount of sleaziness, especially when courting Rose.

"We will find Agnes," the double talking Edward (Julian Rhind-Tutt) assures his grandfather.

The first week’s episode ends with two shots fired in the dark and Oliver’s outcry. In Dickens’s tale, Rose Maylie lived in the mansion that Sikes was about to rob. Had this adaptation been more faithful to the book’s plot, she would have found Oliver and nursed him back to health, but Bill Sikes carries the wounded boy back to London instead, where Nancy nurses him. The tale ends with Oliver reunited with Mr. Brownlow and Rose; Nancy, Bill Sikes, and Fagin dead; Mr. Brumble marrying Mrs. Corney; and Edmund disgraced and disinherited.

Young William Miller, like all the Olivers before him, looks angelic. I found it strange, however, that despite being raised in the workhouse with the likes of Mr. Brumble and Mrs. Corney, his accent is so refined. And where did he learn his exquisite manners? Would nature truly be so triumphant over nurture in such a hard scrabble world? I think not, but this is not this production’s only failing.

Mrs. Corny tries to blackmail Monks.

While Mr. Brumble and Mrs. Corney do marry, as in the film, their tale does not end at the altar. They squander their ill gotten gains and wind up in the workhouse without hope of leaving and experiencing the same lack of compassion that they had meeted out.

Fagin guilty on all counts

In the book Edward teams up with Fagin – a sinister character as Dickens describes him and without a hint of the lovable traits depicted by Timothy Spall – to hunt after Oliver. In Dickens’ plot, Edward (Mr. Monks) is not cast out without a penny. After receiving half his inheritance from Mr. Brownlow, who hopes he will redeem himself, Edward travels to America, where he squanders his fortune and dies destitute in prison. Seeing him grovel in the film just did not seem quite in character and I found the scene distasteful and discordant.

Oliver Returns

While the second half of this tale was much darker than the first installment, which was grim enough, the film’s pacing had me sitting on the edge of my seat towards the end. Fagin’s death was swift and merciless, and the deft visual touch of the Artful Dodger walking away with Bill Sikes’ dog showed how quickly life moves on. Before Fagin lay cold in his grave, his position had been replaced by one of the boys and his passing went largely unnoticed, except for the crowd. Such hanging scenes were common back then, and vendors sold food and drink as if the crowd was attending an entertainment, which in a strange way they were. As for Sikes, in the book he dies in a gristly accident running from an angry mob. Death by his own hand seemed just a bit too merciful an ending for a merciless and inhumane man.

If you missed the second installment of this adaptation, click here to view it online. The video will be available on PBS’s site from Feb 23 – March 1.

More Links:

Read Full Post »

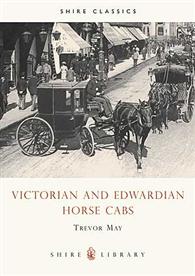

Another book review so soon on this blog? Well, yes. This book from Shire Publications, Victorian and Edwardian Horse Cabs by Trevor May, is short, just 32 pages long, but it is filled with many facts and rare images of interest to lovers of history. In Jane Austen’s day most people walked to work, town, church, and market square, or to their neighbors. Six miles was not considered an undue distance to travel by foot one way. The gentry were another breed. They either owned their own carriages or hired a public horse cab. These equipages were available as early as the 1620’s.

Another book review so soon on this blog? Well, yes. This book from Shire Publications, Victorian and Edwardian Horse Cabs by Trevor May, is short, just 32 pages long, but it is filled with many facts and rare images of interest to lovers of history. In Jane Austen’s day most people walked to work, town, church, and market square, or to their neighbors. Six miles was not considered an undue distance to travel by foot one way. The gentry were another breed. They either owned their own carriages or hired a public horse cab. These equipages were available as early as the 1620’s.