Gentle readers, I am often asked questions by readers, some of which I answer and some of which go unrecognized. Be assured that if you are a student looking for me to do your research when all you have to do is poke into my pages, I shall remain silent. But if your question is intriguing enough, I might be stirred to action. Such is the case with Craig Piercey’s recent question, which goes like this:

Hi Vic

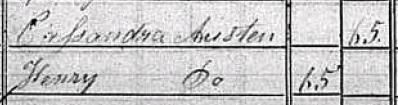

I was rummaging through the Census of 1841 when I came across something interesting. It lists Cassandra Austen of Chawton as 65 however, she died in 1845 aged 72 years. So, something is not right somewhere, either the census is wrong, there were two Cassandra Austen’s in Chawton (unlikely) or her age is wrong on her Grave Stone.

I enclose the census ledger – its on page 8 half way down. It has her listed as being of independent means.

Let me know your thoughts.

Cheers

Craig.

I could not give Craig an intelligent answer, for the first thought that came to me was that vanity had caused her to give the census taker a wrong age, but then I reasoned that perhaps an honest mistake had been made. I next thought of Tony Grant, who writes for both my blogs. Tony, a retired teacher, arranges customized tour packages for small groups of tourists. His resources are varied, and because he lives in England, he has quick access to historical registers and individuals who can help him. I asked Craig if I could share the question with Tony.

Hi Vic

Please feel free.

What confuses me is, somebody would have had to go round the houses in the village as it looks like the ledger was done by hand – no forms here… So, I’m guessing the nominated person must have actually met her and asked her her age. This would make the age on the Census probable but of course, not completely reliable. I seem to recall somewhere that it was originally clergymen who filled in the Census forms making her age being wrong even more unlikely as the clergyman at the time was her Nephew I think…

As for her grave stone… Well, I have never been to the church or the Great House, although I have been to her house and what I can say is that I have seen pictures of Cassandra’s grave and it look like it may have been moved as there was a fire in the late eighteen hundreds which gutted the original church and maybe the grave stones as well… Who knows, the age on the stones could be wrong… But, unlikely as there would have been family alive that would have known her intimately and surely would have noticed.

I would be interested to know the findings from this, maybe I’m just being stupid and have missed something obvious but, I think not.

Hope you are well, always a pleasure.

Craig.

After Tony returned from yet another of his tour excurions, I put the question to him. Still logy from his trip, he responded off the cuff:

Hi Vic

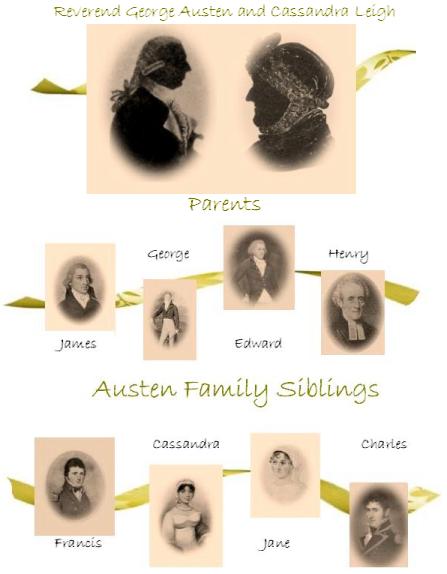

There were two Cassandras. Mrs Austen was also called Cassandra. This is off the top of my head…

Here’s a picture of the Chawton Church yard. Tell me if this answers the question.

No it doesn’t. Just checked Craig’s message. Need to look at this further.

Tony then got in touch with the Hampshire records office in Winchester, and “asked them about the discrepancy between the census of 1841 and the inscription on Cassandra’s grave stone.” The answer came almost immediately.

Hi Vic,

Hampshire archives are on the ball today. They got back to me. Here is what they said:

Dear Mr. Grant,

Thank you for your enquiry.

Indeed Cassandra Austen was 72 at the time of her death, her birth being in 1773. I checked the 1841 census and I must admit Cassandra’s age does appear to be 65 on the census return. Her Brother, Henry, born in 1771, is correctly recorded as being 65 and Cassandra should, depending on the date of the census, be recorded as being 68. Either, the census enumerator recorded her age incorrectly at the time of the cenus or there could be a possibility that the number 65 is badly faded and the five was originally an 8 as the original copy of the census return is quite badly faded. Apart from this it is a mystery why she would record her age as 65.

I hope this is of some assistance to you.

Yours Sincerely

Steve JonesSteve Jones, Archives and Local Studies Assistant

Tony still wasn’t finished.

Hi Vic,

Just had a close look at the copy of the 1841 census you attached. There is no way that 5 was an 8. Somebody made a mistake in recording her age.They probably recorded Henry’s first,correctly as 65 and then got overawed by the domineering presence of Cassandra and either didn’t ask her her age or misheard out of confusion and recorded the same age as her brother.

You can just imagine the scene.

ANOTHER little dramatic episode one of our ,”writers,” could use.

All the best,

Tony

And there you have it, readers. Sometimes even the simplest question involves a great deal of thinking and searching. I am not sure we will ever solve the mystery, but I believe Tony and the Hampshire Records Office got as close to solving the mystery as anyone.

Update: But wait! The plot thickens. Who is the Henry below Cassandra Austen? If Henry Austen was born in 1771, he would have been 70 at the time of the census. Could the census taker have gotten the ages of both siblings wrong, or is this another Henry listed below Cassandra? I find it curious that his last name is not listed as Austen. The case becomes curiouser and curiouser.

Update #2: Laurel Ann pointed me to the site of the 1841 Census, which states,

Age and sex of each person:

Ages up to 15 are listed exactly as reported/recorded but ages over 15 were rounded to the nearest 5 years

(i.e. a person aged 53 would be listed on

the census as age 50 years).

If that is the case, what about Henry, who is already 70? His age would then be listed wrong, not Cassandra’s.

Thank you Craig and Tony for providing the content of this most enlivening and enlightening post! Vic

Update #3: Sarah Parry and Ray Moseley from Chawton House discussed the 1841 Census, as did Laurel Ann from Austenprose, which I featured on this post. Along with the comments below, we have a fairly comprehensive answer to the question. Thank you all for participating.

More about Tony Grant:

- Read his blog, London Calling

- Jane Austen Went to School