Inquiring readers: One of the activities I have missed the most during this year of COVID-19 is traveling abroad. In this blog post, Tony Grant takes us on a tour to The Vyne, which is one of England’s grand houses and is closely associated with Jane Austen and her family. Enjoy!

Gentle readers: Please note: this post is updated with corrections about the Stained Glass Windows and Flemish Tiles, as indicated in the comments by Stuart Hall, Tour Guide, The Vyne.

The Vyne, Sherborne St John Hampshire, Image from Wikipedia

The Vyne, Sherborne St John Hampshire, Image from Wikipedia

The Vyne, is an 18th century mansion near the village of Sherbourne St John. It is just north of the town of Basingstoke; eight miles from Steventon, which is located south west of Basingstoke; eighteen miles from Chawton; twenty miles north of Winchester; and just over fifty miles from the centre of London. It is a typical grand house that, although its present appearance is 18th century, has been developed and adapted over the centuries to fit different periods. In the late 18th century its proximity to Basingstoke and Steventon put it and the Chute family, who owned it, within Jane Austen’s family local connections. George and Cassandra Austen, after their marriage in Bath, moved to Steventon in 1764 when George and Cassandra Austen first took up the living of Steventon Parish and were set to start their family with their first child, James, born on February 13th, 1765. Jane, the Austen’s eighth child, was born 16th December, 1775. As the vicar of Steventon, George Austen associated with the country gentry and landowners in the area and these included the Chutes at The Vyne in Sherborne St John.

The Vyne Estate, The National Trust Map, image by Tony Grant

The Vyne was first built as a large Tudor mansion by William, 1st Lord Sandys, Henry VIII’s Lord Chamberlain who died in 1540. The King himself, was entertained three times at The Vyne by Lord Sandys. The wealth of the Sandys family declined slowly through the centuries, but the Civil Wars 1642 – 1651 finished the family as an authority in the country and their wealth declined drastically. In 1653 the estate was sold to Chaloner Chute, who was the Speaker in the House, a role which had great power in Parliament shaping how Parliament debated issues and passed legislation during the last Commonwealth. The Commonwealth was set up after the execution of Charles 1st and continued to a little after Oliver Cromwell’s death and the reinstatement of the monarchy. Chaloner Chute was a very important man in the country. He reduced the size of the original Tudor mansion and modernised it, employing John Webb, a talented pupil of Inigo Jones to redesign it.

The floor plan of The Vyne, The National Trust

The floor plan of The Vyne, The National Trust

Chute died in 1659 and not much more was done to the house for the next hundred years. His great grandson, John Chute (1701-76) inherited the house in 1754. John Chute was a talented architect and along with his friend Horace Walpole helped Walpole design the Gothic interiors of Strawberry Hill, Walpole’s house at Twickenham. Along with Walpole he also redesigned the Gothic interior of the chapel at The Vyne. In his early thirties, he brought back mementoes from his grand tour of Europe which remain in the house today.

John Chute died without heirs in 1776 and the house passed to his cousin Thomas Lobb (1721-90), the son of a Thomas Lobb of Norfolk who had married Elizabeth Chute (d 1725) in 1720, hence the family connection. This second Thomas Lobb assumed the name of Chute when John Chute died and passed the Vyne to him, thus keeping the family name extant. Thomas (Lobb) Chute married Anne Rachael Wiggett (1733-90) in 1753.

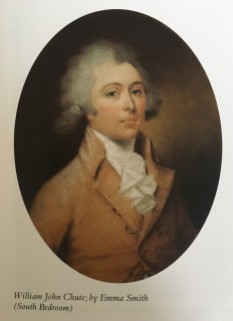

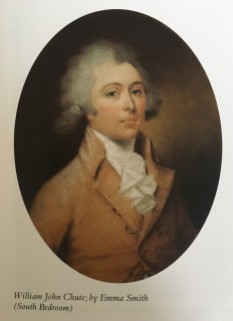

They had two sons, William John Chute (1757-1824) and Thomas Chute (1772-1827). William, who inherited the house in 1790, married Elizabeth Smith in 1794.

Upon his death in 1824 the Vyne passed to his younger brother Thomas, a clergyman. As neither William nor Thomas had issue, the house was left in 1827 to William John Chute’s godson and part of the Wiggett family, William Lyde Wiggett (1800-79). THIS William assumed the name of Chute in 1827 and succeeded to the Vyne in 1842 when Elizabeth Smith Chute passed away.

Image of William John Chute, by Emma Smith. The National Trust

James Austen, Wikipedia Public Domain

.

James Austen, Jane Austen’s eldest brother (above image on the right), became a close and lifelong friend of Tom Chute, William John Chute’s brother. They both loved fox hunting and often rode with the hounds together. On his clergyman’s income, James Austen was able to keep his own pack of hounds. As rector of Steventon, George Austen, Jane’s father, was also a visitor to the Chute family home.

In Pride and Prejudice, Mrs Bennet and the Bennet girls were all a flutter at wealthy landowners, such as Fitzwilliam Darcy, came to live in their neighbourhood. The game was on to get her daughters married into a wealthy strata of society and rise in the world. You had to be ambitious if nothing else and take a chance.

The local clergy were regularly invited to the local landowner’s home for dinner; they became almost a part of the family in many ways. Mr Collins waxed lyrical about his great honour of being invited to Rosings by Lady Catherine de Bourgh.

“She had asked him twice to dine at Rosings and had sent for him only the Saturday before to make up her pool of quadrille in the evening… she made not the smallest objection to his joining in the society of the neighbourhood.”

We can gather that James Austen became closely associated with the Chute family, first because of his father’s connections and subsequently as the vicar of Sherborne St John, the parish in which The Vyne was located. Later he took over the incumbency of Steventon Parish from his father, a mere eight miles from The Vyne, which kept him close to the Chutes and the great house.

James accumulated parishes throughout his clerical career. Deirdre le Faye enumerates the following.

“curate of Stoke Charity , Hants, 1788, (the year he completed his studies with an MA from Oxford), the curate at Overton Hants in 1790, the vicar at Sherborne St John in 1791, the curate of Deane in 1791, the vicar of Cubbington in 1792, the perpetual curate of Hunningham in 1805 curate of Steventon (under his father) in 1801 and finally the vicar of Steventon between 1805 and 1819 (died 1819).”

James is buried alongside his wife in Steventon Churchyard. Image courtesy of Tony Grant.

Jane and Cassandra fully took part in local society, including friendships formed through family associations and connections provided by their father and brothers. Jane often wrote about her acquaintances and the local activities she took part in, including information she knew Cassandra would be interested in, often referring to the Chutes of The Vyne.

Thursday 14th – Friday 15th January 1796

“Friday- At length the Day is come on which I am to flirt my last with Tom Lefroy, and when you receive this it will be over- My tears flow as I write, at the melancholy idea. William Chute called here yesterday. I wonder what he means by being so civil. There is a report that Tom ( Chute) is going to be married to a Litchfield Lass.”

On Saturday 1st November 1800, Jane went to a ball , presumably at Basingstoke.

“It was a pleasant ball, and still more good than pleasant, for there were nearly 60 people and sometimes we had 17 couples-The Portsmouths, Dorchesters, Boltons, Portals and Clerks were there and all the meaner and more unusual etc etc’s- There was a scarcity of men in general and a still greater scarcity of any that were much good for much .- I danced nine dances out of ten, five with Steven Terry, T. Chute and James Digwood and four with Catherine-“

Saturday 9th November 1800

“Mary fully intended writing to you by Mr Chutes frank and only happened intirely (JA’s spelling) to forget it- but will write soon-“

On Saturday3rd January 1801 Jane saw Tom Chute when she visited Ash Park. On Friday 9th January a few days later she saw him again at Deane. These are all houses belonging to the local gentry in Hampshire.

On Monday 22nd April 1805 she hears of Tom Chute’s fall from a horse.

“I am waiting to know how it happened before I begin pitying him.”

On the 8th January 1807, Jane adds another news item to her letter to Cassandra

“…. and another that Tom Chute is going to settle in Norfolk.” This was of course where another Chute family property was located, through the Wiggett connection.”

In January 1813, she again refers to the use of Mr Chute’s franks.

And probably most intriguing of all on Wednesday, February 26th 1817 Jane writes,

“I am sorry to hear of Caroline Wiggetts being so ill. Mrs Chute would feel almost like a mother in losing her.”

The reference to using the Chutes’ “frank” refers to the means by which the Chutes addressed an envelope. The MP wrote the address, dated it properly, and wrote the word “FREE” in the middle of his signature. This meant that the recipient of the letter didn’t pay for its delivery (which was the custom), but that the Chutes would pay. At the time of this last message Jane was still in the process of writing Sanditon and she had a mere few months left to live. Jane died in Winchester on the 18th July 1817. The Chutes remained in her sphere of interest to the last.

Claire Tomalin makes links between Jane Austen’s real life associations, the Chutes, etc., and some of her novels’ characters. She surmises that William John Chute and Elizabeth Chute nee Smith could have inspired some of her ideas about Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy. Jane and Elizabeth Chute did not become great friends but Elizabeth Chute was well read and was an intelligent person from all accounts. There is also the matter of Caroline Wiggett, who was mentioned in the letter above. Caroline was a second cousin of William’s mother, who came to live with Elizabeth and William and thought of them as her Aunt and Uncle. She was brought up at The Vyne from 1803. From Caroline’s reminiscences we learn that she had a rather lonely childhood at The Vyne. Could she have been an inspiration for Fanny Price in Mansfield Park? Tomlin rightly warns us about making too many assumptions. Writers use many experiences from their lives but use them creatively within their works. A writer will not use personal experiences in a factual way, but aspects of their experiences can inevitably be adapted, drawn upon, and used fictionally.

However, what attracts me most about Jane’s letters, which is clearly obvious in the quotations above, is her humorous tone, often teasing, and making fun of those people and situations she writes about. Of course these letters are private letters to her dear sister Cassandra. She and Cassandra would have had their private jokes and opinions, not for publication. Haven’t we all?

Eventually in 1956, upon the death of Sir Charles Chute, the final Chute owner, The Vyne was bequeathed to The National Trust, who take care of the house today. It is open to the public.

National Trust Membership card.

National Trust Membership card.

A few years ago, Emily, one of our daughters, bought us a National Trust membership as a Christmas present. The trust looks after hundreds of old houses, estates, gardens, coastal paths and wild areas of the British Isles. With membership we get free entry into these estates, gardens and historic houses, which is an amazing thing.

In March 2017, Marilyn and I went to visit The Vyne. I had heard of the Austen connection, of course, and also the connection with Horace Walpole (1717-1797) and the Gothic Revival movement. After university, Emily had worked as an intern at Strawberry Hill House, Walpole’s mansion at Twickenham, and we visited Strawberry Hill with Emily as our guide. We were expecting to see something of the Gothic Revival style of interior design at The Vyne, just as we had seen at Strawberry Hill.

Sherborne St John. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

Sherborne St John. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

I have focused a lot of this article on the period when the Austens lived at Steventon and on the connections between the Austen family and the Chutes. In an earlier period, Horace Walpole was best friends with John Chute (1701-1776) before William John Chute and Thomas Chute, the Austens’ acquaintances.

The Vyne is rich in objects and paintings brought to The Vyne after John Chute returned from his grand tour of Europe. At 39, John was older than his fellow travellers. His cousin Francis Whitehead, who he went on tour with, was 23, and the friends he made on the tour, including Horace Walpole, were virtually a generation younger.

Porcelain brought back by John Chute from his Grand Tour. Image courtesy of Tony Grant.

Porcelain brought back by John Chute from his Grand Tour. Image courtesy of Tony Grant.

Marilyn and I entered through the entrance on the south side overlooking the extensive surrounding parkland and the lake. Each room is attended by a guide. Once you ask a question you are inundated with the most interesting and detailed, in-depth information about the Chutes, the house, and the very room you might be standing in at the given moment.

The library. Image from The National Trust

The library. Image from The National Trust

We walked through the rooms packed with objects and paintings. The library has two large globes of the world, a fantastic ornate baroque fireplace, full length portraits of the Chutes, and walls with shelf upon shelf of books. I must admit to a quirky disposition when I walk through libraries in old houses. You must not touch the books. They are rare, ancient, bound in leather and cost a fortune. I have an enormous urge, which I have to fight against, to spend time with the said books, take them off the shelves and read them. It is always a difficult time having to merely walk past them. I spent a moment reading the titles on the spines though.

We walked along the oak gallery, the walls lined with portraits and landscapes. The floor is of oak timbers. The walls are faced with oak wainscoting with an intricate “folded linen” effect carved and finely chiselled into the surface of each panel. They are similar to the panelling I have seen in the Tudor Palace at Hampton Court and other Tudor mansions around the country. This is a fantastic example of the Gothic Revival on the walls, created in the 18th century and not the 16th century.

Linen fold oak panelling. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

Linen fold oak panelling. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

The chapel attached to the eastern wing of the house is a sight to behold. It is the epitome of Gothic Revival. We think Jane Austen did visit The Vyne, so there is a good chance she too gasped at what you see today. Horace Walpole advised on the decoration. John Chute employed an Italian craftsman called Spiridore Roma, who worked on the chapel between 1769-1771. He used a technique called trompe l’oeil, to create a three dimensional effect of buttresses, Gothic arched windows, and fan ceilings.

Trompe l’oeil in the chapel. National Trust image.

Trompe l’oeil in the chapel. National Trust image.

I have seen the real thing in Bath Abbey and other medieval churches and cathedrals and it is obvious that this is not the real thing, but this paint effect is very impressive indeed. There are medieval-styled tiles on the floor and stained glass windows–all of 16th century medieval originals. The effect is glorious.

Image of Tudor Revival Gothic floor tiles, courtesy of Tony Grant

Next to the chapel is the Tomb Chamber. It is set out like a Gothic cathedral chapter house. It has valuabele 16th century stained glass windows and a stone slab floor, but the centre piece is a table tomb with a reclining white marble statue of Speaker Chute (Chaloner Chute 1595- 1659) lying full length with his head propped up on an elbow. Horace Walpole wanted to create the emotions derived from Gothic architecture and in this chapel and tomb chamber he aided John Chute, his friend in recreating that Gothic moment.

Chaloner Chutes tomb. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

Chaloner Chutes tomb. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

After our tour inside the great house Marilyn and I walked in the grounds. We had a wonderful view of the long lake, smooth green lawns, and the massive cedar trees. We went inside the brick summer house and looked up at its web-like beamed ceiling.

The Summer House. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

The Summer House. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

We walked through the walled garden where the National Trust is recreating a great houses kitchen garden with a variety of shrubs, fruit trees, herbs and vegetables.

The walled kitchen garden. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

The walled kitchen garden. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

We walked along the Lime Walk and listened to the wind in the branches and birds singing in the canopy.

The lawns and lake at the front of The Vyne. Image courtesy of Tony Grant

Visiting a National Trust property such as The Vyne lifts the spirits, and provides beauty, natural and man-made, that soothes the soul. Afterwards, we drove into the village of Sherborne St Peter nearby and walked to the church where James Austen was vicar.

References:

“The Vyne Hampshire,” published by The National Trust 1998 (revised 2015)

Jane Austen A Life, by Claire Tomalin published by Penguin Books 1997.

Jane Austen’s Letters Collected and edited by Deirdre Le Faye (Third Edition) Published by Oxford University Press 1997.

Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen Published by Penguin Classics 1996

Mansfield Park, by Jane Austen Published by The Penguin English Library 1966

Tony Grant Posts:

Read Full Post »