Inquiring Readers: This is the third of four posts in honor for Pride and Prejudice Without Zombies, Austenprose’s in-depth reading of Pride and Prejudice. My first post discussed Dressing for the Netherfield Ball and my second post talked about the dances. This post discusses the suppers served during Jane Austen’s era, and concentrates on what kinds of food and drink might have been served at the Netherfield Ball.

“As for the ball, it is quite a settled thing; and as soon as Nicholls has made white soup enough I shall send round my cards.” – Charles Bingley, Pride and Prejudice

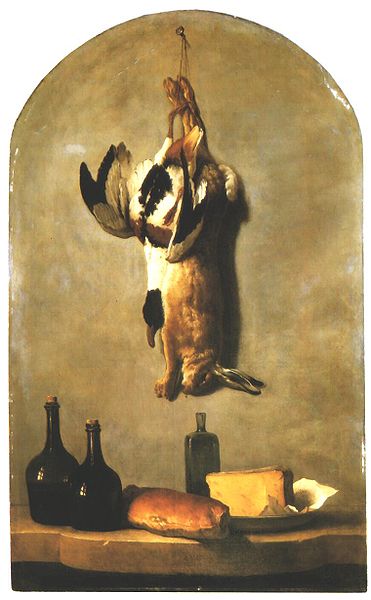

Mr & Mrs Bennet sit down to supper. Notice the lavish bowl of fruit.

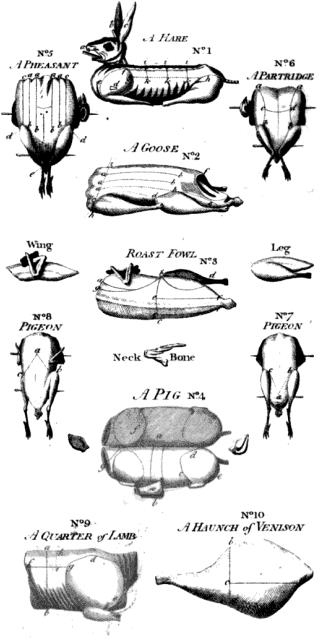

The sit-down supper served at the Netherfield Ball in Pride and Prejudice probably occurred around midnight. By that time, people would be famished after their physical exertions or from playing cards nonstop in the card room. They had most likely eaten their dinner between 3-5 p.m. (earlier in the country, and later in Town). Dinners consisted of between 5-16 dishes and could last several hours. The best families would serve up two courses, for a meal’s lavishness depended on the number of courses and dishes that were served. Dishes representing a range of foods, from soups to vegetables and meats, would be spread over the table in a pleasing arrangement and would be set down at the beginning of the meal.

Large Derby porcelain supper dish from Ruby Lane

It is conjectured that by the time the covered dishes arrived from the kitchen and the family and guests were seated, the food had turned cold. Diners would be confined to eating from the dishes placed closest to them. In the Bill of Fare from the Universal Cook, 1792 (Francis Collingwood and John Woollams) one can see the foods that were available in November.

Bill of Fare, November 1792

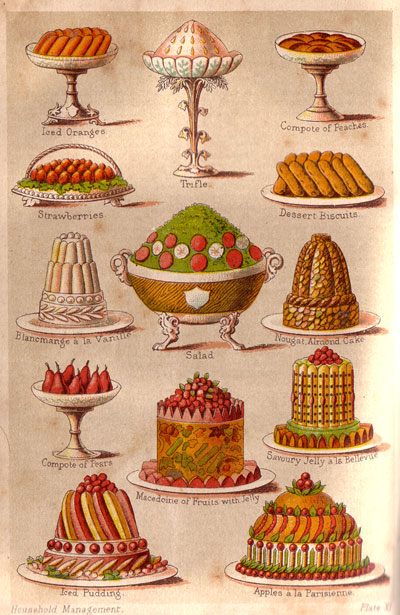

The evening meal, which also included a dessert course, lasted as long as two hours, leaving the diners sated. Suppers were therefore served quite late and were simple and small in comparison. Often called a “tea board”, this small repast was frequently served on a tray between 10-11 p.m. If more than one person was hungry, a cloth would be laid on a small table, not the dining table, and a limited assortment of cakes, tarts, biscuits, pastries, jellies, cheeses, cold meats, sandwiches, savories, salad, dessert, or local fruits – whatever was at hand – would be made available. (One can imagine how tired the servants must have been, rising early as they did.)

Mr. Darcy observes the Bennet family during supper and is accosted by Mr. Collins

Suppers served at private balls were an entirely different matter for they reflected on the splendor of the event. Balls generally began at 8-9 p.m. and the dancers sat down to a lavish spread at 11 p.m. or midnight. A gentleman accompanied his dance partner into the supper room, which makes one think that it would have been wise for a suitor who wished to further his acquaintance with a young lady to reserve a dance just before the meal.

Jane and Elizabeth at supper

Mr. Bingley most likely served a sumptuous supper on a magnificent table set with his finest china and silver. The food would consist of white soup, which during this time was made with veal stock, cream, and almonds; cold meats, such as chicken or sliced ham; poached salmon; glazed carrots and other seasonal vegetables; salads; fresh fruits;biscuits;dry cake (which meant unfrosted cake, like the pound cake recipe from the Delightful Repast at the bottom of this post); cheeses; short-bread cookies; pies; ice-cream; and trifles. One must not forget that during this period cockscombs and testicles were considered delicacies, and that bone marrow was routinely added to pies for richness. (Fancy Tripe or Trotters for Supper?)

Kitty and Lydia tippling, Netherfield Ball, P&P 2005

Drinks of tea, coffee, lemonade, white wine claret, and red wine (sweet madeira wine was especially popular) were served. Regency cups were filled with punch, negus (wine mixed with hot water, lemon and nougat); orgeat (made with a sweet syrup of orange and almonds); or ratafia (a sweet cordial flavored with fruit or almonds). Port was reserved for gentlemen, though I am not sure that they were allowed to imbibe this liquor in front of the ladies.

A footman holds a tray of drinks, Netherfield Ball, P&P 2005

A private midnight supper at Netherfield was a more splendid affair than the suppers served up at the weekly Wednesday night balls at Almack’s. These subcription dances coincided with the three months of the London social season. Alcohol was not served to discourage drunkenness among gentlemen, who were known to imbibe several bottles of wine per day, and only an assortment of thinly sliced stale bread (which was a day old), dry cakes, lemonade and tea were provided. Simpler balls given by hosts who were not as rich as Mr. Bingley might offer a little bit of hot supper consisting of six dishes, including salad, dessert, and fruit, and coffee, tea, lemonade and wine.

Trifle, The Delightful Repast

The links to the two recipes in this post were created expressly for us by Jean at The Delightful Repast. The pound cake (dry cake) recipe is one that even I am able to attempt with some success, and Jean’s solution of serving trifle in individual dessert dishes is sheer genius.

The last to leave the Netherfield Ball. Kitty and Lydia sleeping off their drinking. P&P 2005

The Food Timeline shows when meals were served during the Georgian and Regency periods, and how the hours changed.

- 1780: Breakfast 10AM; Dinner 3-5PM, Tea 7PM, Supper 10-11PM

- 1815: Breakfast 10AM (leisurely), 9AM (less leisurely), 8AM (working people); Luncheon Midday; Dinner 3-5PM; Supper 10-11PM

- 1835: Breakfast, before 9AM; Luncheon (ladies only) Midday; Dinner 6-8PM; Supper depending upon the timing and substantiality of dinner

Read Full Post »