When Jane Austen wrote letters to her sister or brothers, she had the choice of sending them two ways: One was to assume her siblings would pay to receive her letters. The other was that Jane would pay to send the letter. As we know, Jane lived on a budget of a mere £50 per year, as did Cassandra, and so their letters were crossed to save money on weight and pages.

Letter to Godmersham

In the following passage from Mansfield Park, Jane writes about 10 year old Fanny Price’s dilemma: She wants to write to her brother William, the sibling she loves the most, but she has no paper on which to write him, and even if she had the paper, she has no funds to send the letter. Her cousin Edmund offers a solution.

“My dear little cousin,” said he, with all the gentleness of an excellent nature, “what can be the matter?” And sitting down by her, he was at great pains to overcome her shame in being so surprised, and persuade her to speak openly. Was she ill? or was anybody angry with her? or had she quarrelled with Maria and Julia? or was she puzzled about anything in her lesson that he could explain? Did she, in short, want anything he could possibly get her, or do for her? For a long while no answer could be obtained beyond a “no, no—not at all—no, thank you”; but he still persevered; and no sooner had he begun to revert to her own home, than her increased sobs explained to him where the grievance lay. He tried to console her.

“You are sorry to leave Mama, my dear little Fanny,” said he, “which shows you to be a very good girl; but you must remember that you are with relations and friends, who all love you, and wish to make you happy. Let us walk out in the park, and you shall tell me all about your brothers and sisters.”

On pursuing the subject, he found that, dear as all these brothers and sisters generally were, there was one among them who ran more in her thoughts than the rest. It was William whom she talked of most, and wanted most to see. William, the eldest, a year older than herself, her constant companion and friend; her advocate with her mother (of whom he was the darling) in every distress. “William did not like she should come away; he had told her he should miss her very much indeed.” “But William will write to you, I dare say.” “Yes, he had promised he would, but he had told her to write first.” “And when shall you do it?” She hung her head and answered hesitatingly, “she did not know; she had not any paper.”

“If that be all your difficulty, I will furnish you with paper and every other material, and you may write your letter whenever you choose. Would it make you happy to write to William?”

“Yes, very.”

“Then let it be done now. Come with me into the breakfast-room, we shall find everything there, and be sure of having the room to ourselves.”

“But, cousin, will it go to the post?”

“Yes, depend upon me it shall: it shall go with the other letters; and, as your uncle will frank it, it will cost William nothing.”

“My uncle!” repeated Fanny, with a frightened look.

“Yes, when you have written the letter, I will take it to my father to frank.”

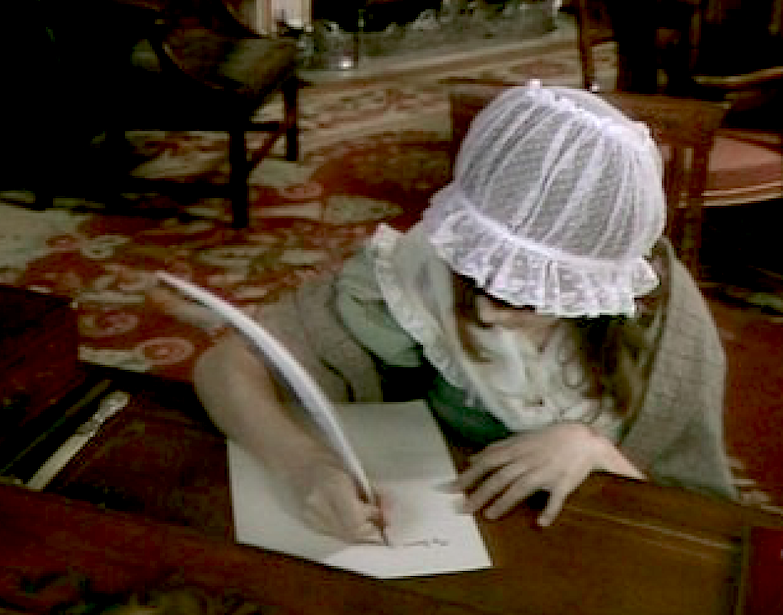

Fanny writes William a letter. (Mansfield Park, 1983)

Fanny thought it a bold measure, but offered no further resistance; and they went together into the breakfast-room, where Edmund prepared her paper, and ruled her lines with all the goodwill that her brother could himself have felt, and probably with somewhat more exactness. He continued with her the whole time of her writing, to assist her with his penknife or his orthography, as either were wanted; and added to these attentions, which she felt very much, a kindness to her brother which delighted her beyond all the rest. He wrote with his own hand his love to his cousin William, and sent him half a guinea under the seal. Fanny’s feelings on the occasion were such as she believed herself incapable of expressing; but her countenance and a few artless words fully conveyed all their gratitude and delight, and her cousin began to find her an interesting object. He talked to her more, and, from all that she said, was convinced of her having an affectionate heart, and a strong desire of doing right; and he could perceive her to be farther entitled to attention by great sensibility of her situation, and great timidity. He had never knowingly given her pain, but he now felt that she required more positive kindness; and with that view endeavoured, in the first place, to lessen her fears of them all, and gave her especially a great deal of good advice as to playing with Maria and Julia, and being as merry as possible.

From this day Fanny grew more comfortable. She felt that she had a friend, and the kindness of her cousin Edmund gave her better spirits with everybody else. The place became less strange, and the people less formidable; and if there were some amongst them whom she could not cease to fear, she began at least to know their ways, and to catch the best manner of conforming to them.”

Edmund’s solution was a third option not available to Jane or her family. Franking privileges were available to all peers and sirs, like his father, Sir Thomas Bertram, a baronet. He who would write his name diagonally across the sealed letter. This act automatically paid for the postage. — Regency Trivia: Franking Privileges, Ella Quinn

This scene sets the stage for the special relationship between the lonely, bewildered Fanny and her kind cousin, who has made her feel welcome and at home at a time when she felt adrift. Their connection would stand the test of time.

More on the Topic:

The Regency Post — A Pity We’ve Lost Letters, Shannon Donnely’s Fresh Ink