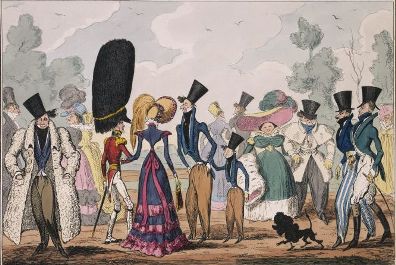

Ah, the novels of Jane Austen! In my teenaged mind they conjured up romantic tales, white muslin dresses, perfectly coiffed and finely dressed gentlemen, ballroom dancing, visits to Bath, and carriage rides through gentle rolling hills.

Early Austen films from the late 1930s to the 1970s BBC television series, concentrated on immaculate clothes and manners. The people in Austen’s plots lived graceful and beautiful lives. Although she added comic and/or mean characters who helped to make her plots memorable.

But, as I reread Austen’s novels throughout my adulthood, I realized she cared deeply about the plight of the poor and mentioned them frequently in her novels. Emma Woodhouse and Anne Elliott carried baskets of food to the less fortunate. Genteel families put together gift baskets for those who struggled during the holidays. Mrs Smith, Anne Elliott’s friend, lived in an undesirable neighborhood in Bath, and was so penurious that she depended on the kindness of others to survive and made trinkets to supplement her meager income.

The environmental conditions of life in London and nearby cities from 1775, the year of Austen’s birth, through 1817, the year of her death was not mentioned in her wonderful books. But she must have known of the pervasive poverty in England, and especially about the pollution that was recorded in detail by people who lived in those times. Their records reveal that not everything during these years was a bed of roses.

In fact, the reality of life in Georgian London at the start of the 18th century was stark for a majority of the people, especially the poor.

The city was…a very dangerous and unhealthy place. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, and disease led to more people dying each year than being born. With contaminated drinking water, the streets acting as open sewers, and the choking atmosphere, diseases such as cholera, smallpox, and tuberculosis were widespread.” Georgian London 1714 – 1837

St. Paul’s Cathedral, from St. Martin’s-le-Grand Thomas Girtin British 1795–96, Public Domain image, Met Museum.

By 1800, the population had risen to the extent that London was probably the first city in the world with over 1,000,000 citizens. However the average life expectancy across London was still only 30 while in rural England it had risen to over 40.” Georgian London 1714 – 1837

In regard to this last statement, Austen, who died at the age of 41, barely attained the rural ‘over 40” life expectancy. Whereas her immediate family lived longer lives: father 75 yrs, mother 87 yrs, sister 72 yrs: and brothers Edward, 75 yrs, James, 54 yrs, and Francis, 91 yrs. Yet so many poor factory workers or individuals who lived in dire poverty in tenements and suffered from poor nutrition did not survive beyond the age of 30. The poorest died in their 20’s.

An old article in an old online site from the Republic of Pemberley, which has since been updated, discusses Some downsides of Regency London. (long), which includes the environmental conditions caused by pollution before and during Austen’s birth.

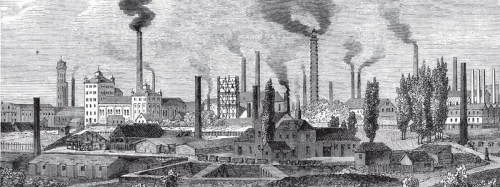

Air pollution: Soot, Fog, and Smog

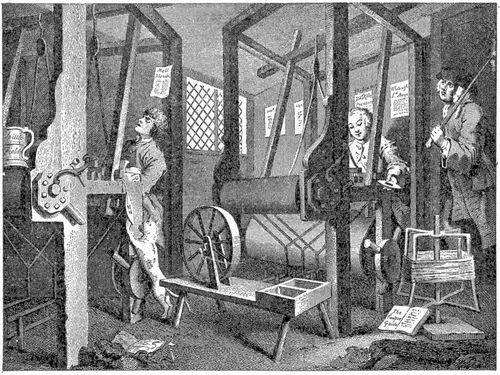

Coal was the primary source for heating and cooking in houses and shops during the 18th & 19th centuries. London and the industrial cities north of London used coal as their primary resource. Major cities produced so much soot that it spread everywhere. Even the spa city of Bath was affected.

Fog and smog were also the main results. In 1817 Sir Richard Phillips described the smoke of London spreading twenty or thirty miles from the metropolis and killing or blighting vegetation. He goes on to say:

“Other phenomena are produced by its union with fogs, rendering them nearly opaque and putting out the light of the sun; it blackens the mud of the streets by its deposits of tar, while the unctuous mixture renders the foot-pavement slippery; and it produces a solemn gloom whenever a sudden change of wind returns over the town the volume that was previously on its passage into the country.” ( “A Morning’s Walk from London to Kew” (page 11) Sir Richard Phillips, 1817. Googlebooks text is online.)

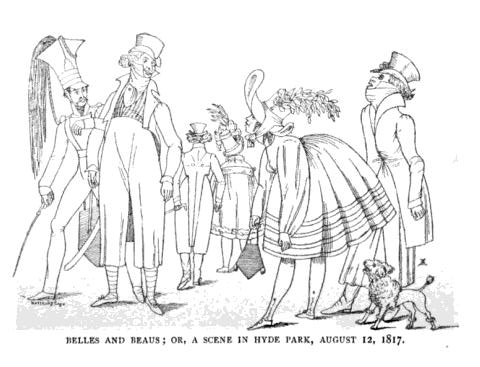

Keeping clothes clean for long was nearly impossible in a city filled with chimneys. Considering the pervasive smoke and soot, one wonders how long delicate white muslin gowns or white shirts would stay clean. One would walk around the city for a few hours, only to find that those garments looked grubby. Wealthy individuals could afford to change their clothes frequently to look respectable, but the working and lower classes did not have such a luxury. Unlike the rich, they could not pay laundresses to wash their clothes frequently.

The consummate Georgian dandy was Beau Brummel, whose first biographer, Captain William Jesse, quoted Brummel as saying about the maintenance of his clothes: “No perfumes, but very fine linen, plenty of it, and country washing.” In other words, those with the means sent their laundry to country villages for a thorough washing.

A more serious effect of all those coal fires in towns and cities, like London and Bath, was smog.

“…unpleasant, choking smog spoilt food, smutted linen and buildings and suffocated vegetation. It also suffocated the citizens. As early as 1610 a surveyor complained that the chimneys proliferating in the country ‘raise so many duskie clouds in the ayre [which] … hinder the heat and light from the Sunne from earthly creatures” (Hubbub: Filth, Noise, and Stench in England, 1600-1770, Emily Cockayne, p. 209, Yale University Press, 2007) Hubbub is also available for free on the Internet Archive

An EPA Journal article written by by David Urbinato in 1994 mentions the following:

“Smog in London predates Shakespeare by four centuries. Until the 12th century, most Londoners burned wood for fuel. But as the city grew and the forests shrank, wood became scarce and increasingly expensive. Large deposits of “sea-coal” off the northeast coast provided a cheap alternative. Soon, Londoners were burning the soft, bituminous coal to heat their homes and fuel their factories. Sea-coal was plentiful, but it didn’t burn efficiently. A lot of its energy was spent making smoke, not heat. Coal smoke drifting through thousands of London chimneys combined with clean natural fog to make smog. If the weather conditions were right, it would last for days.”

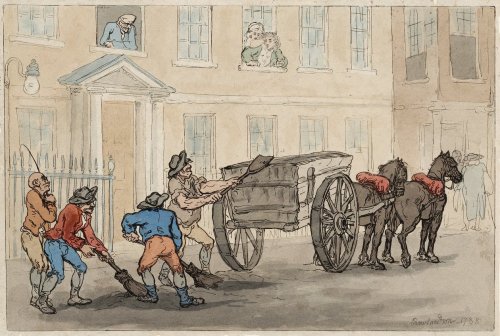

Animal pollution:

In the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century, London was filled with horse manure and urine from the thousands of horses that pulled Hansom cabs and other vehicles. The manure and urine, along with the carcasses of dead horses, polluted the city with the stench and poisoned water, which threatened the health of its residents.

Manure produced:

In London, 50,000 horses produced 570,000 kilograms of manure and 57,000 liters of urine each day. Horses, it was calculated, produced 15–35 pounds of manure per day each.

“Each horse also produced around 2 pints of urine per day and to make things worse, the average life expectancy for a working horse was only around 3 years. Horse carcasses therefore also had to be removed from the streets. The bodies were often left to putrefy so the corpses could be more easily sawn into pieces for removal.” The streets of London were beginning to poison its people.” – The Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894: Historic UK

One should also take into account the number of oxen, mules and donkeys used for hauling. Big dogs pulling carts did their business in the streets as well. Add the drovers who came from all parts of the Kingdom driving livestock to market: the problem of cleaning the streets of effluvium and stench became an almost impossible fight.

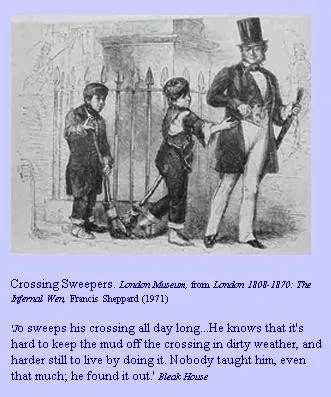

“During Jane Austen’s time and into the earliest days of the twentieth century, crossing sweepers made a living sweeping pedestrian crossings, stoops, and sidewalks of horse manure and litter” – Jane Austen’s World, 2007.

With all that manure, crossing sweepers were essential for moving dirt and droppings out of the way. This link to the article explains how vital poor males were for keeping the crossings clear for pedestrians.

Smithfield Market:

“Between 1740 and 1750 the average yearly sales at Smithfield were reported to be around 74,000 cattle and 570,000 sheep.[43] By the middle of the 19th century, in the course of a single year 220,000 head of cattle and 1,500,000 sheep would be “violently forced into an area of five acres, in the very heart of London, through its narrowest and most crowded thoroughfares”.[44] The volume of cattle driven daily to Smithfield started to raise major concerns. – Wikipedia

It is hard to imagine the noise from bellowing cattle and bleating sheep, the immeasurable amount of excrement and urine deposited as they walked along narrow lanes, the smells from the droppings and their effect on the populace in terms of the unhygienic streets.

“Of all the horrid abominations with which London has been cursed, there is not one that can come up to that disgusting place, West Smithfield Market, for cruelty, filth, effluvia, pestilence, impiety, horrid language, danger, disgusting and shuddering sights, and every obnoxious item that can be imagined…” – Maslen, Thomas (1843). Suggestions for the Improvement of Our Towns and Houses. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 16.

Sewage & Dirty, Fetid Water:

“Most buildings were not connected to the various rudimentary urban subterranean sewerage schemes developing in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Waste water combined with surface rainwater in street gutters known as kennels [street gutters].” (p 195, Hubbub)

Wide roads had gutters on either side, narrow roads had a gutter running down the center. The water in these gutters ran into ditches then into streams, which fed into faster waters, like the Thames, which carried most of the dirty watery waste that came from a combination of households, plus manufacturing wastes that included soap, which bubbled. The gutters needed to be kept free from blockages, if they were not, then the streets flooded or street puddles stagnated. Citizens, often tasked to keep the gutters clean outside their doors, cast rotting fruit and vegetables, dung, and human waste that also blocked the flow of water. (Hubbub, p 195-197)

When the waste was unblocked, it entered the gutters and then was dispensed into streams and rivers that turned into polluted the water.

“Matt Bramble gives his impression of the quality of liquid to be obtained from the Thames: ‘If I would drink water, I must quaff maukish content of an open aqueduct, exposed to all manner of defilement; or swallow that which comes from the river Thames, impregnated with all the filth of London and Westminster – Human excrement is the least offensive part of the concrete, which is composed of all the drugs, minerals, and poisons, used in mechanics and manufacture, enriched with the putrefying carcases of beasts and men; and mixed with the scouring of all the wash-tubs, kennels, and common sewers, within the bills of mortality.” (p 111, SATIRE IN THE EXPEDITION OF HUMPHRY CLINKER BY TOBIAS SMOLLETT, 1771)

Night Soilmen:

“In cities, neighboring privies were placed side by side in yards and drained into a common cesspool located under an alley that ran between the row of cottages or townhouses. In rich to middle class households, nightsoilmen would be paid to cart the waste away when the household was sleeping. This service was quite expensive, and quite often neglected in poorer districts where the lower classes could not (and landlords would not) hire these men until the cesspools were filled to overflowing.” (Privies and Waterclosets, written by David J. Eveleigh, A Jane Austen’s World Review, 2010)

Austen visited her brother, Henry in London three times — to his addresses on Sloan St in 1811 & 1813, and Henrietta St in 1814. While she situated many of her characters living in or visiting London, in her novels she did not mention the horrors of the slaughters that occurred in Smithfield Market, the sounds of fearful animals, their horrific deaths, and their blood running in the streets as their carcasses were dismembered, not to mention the stench.

These events did not play a part in her plots, which had an undercurrent of dark moments as well. We must assume that Austen knew more about London’s pollution, its filthy air, and rutted roads covered with excrement. She simply chose to use only the moments she needed to drive her stories forward. Her two last novels had serious undertones. One wonders that, had she lived longer, if the darker edges of Georgian life would have crept deeper into her plots.

Additional Links:

- This post was influenced by Emily Cockayne’s book, which I purchased in 2007 and have used for research since. (Hubbub: Filth, Noise, and Stench in England, 1600-1770, Emily Cockayne, Yale University Press, 2007) Hubbub is also available for free on the Internet Archive

- Over two hundred Years of Deadly Air: Smogs, Fogs, and Pea Soupers, The Guardian

- *3 Nelson’s Column When we clean up old buildings, do we erase history? [Part One] | Azerbaijan Days

- Yorkshire, r/CasualUK When one neighbour washes their wall you can really see the effects of air pollution (Yorkshire) : r/CasualUK

- Incredible photos show before and after London’s most famous landmarks were cleaned of grime and soot – MyLondon

- Privies and Water Closets, David J. Eveleigh: A review