By Brenda S. Cox

“Your letter to Adlestrop may perhaps bring you information from the spot . . .”–Jane Austen writing to her sister Cassandra about a relative in Adlestrop they loved, Elizabeth Leigh, who was very ill. Jan. 10, 1809

I’ve just finished a fascinating little book, Jane Austen & Adlestrop: Her Other Family, by Victoria Huxley. Huxley tells the stories of Austen’s Leigh relatives alongside frequent quotes from Austen’s works as well as other contemporary sources. I highly recommend this book, but I’ll share some highlights.

We know Jane Austen didn’t take her characters or situations directly from life. And yet, for every author, the experiences we have and hear about, and the people we know and know of, are all grist for the mill. They come together in new shapes and forms as we write. Jane Austen was close to her Leigh relatives, so it’s not surprising their lives fed into her novels in various ways.

The Leigh Family

Jane’s mother Cassandra Leigh Austen was from an old family descended from a Lord Mayor of London, Sir Thomas Leigh (1498-1571). During Sir Thomas’s lifetime, King Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries, making much land available for purchase. Sir Thomas invested widely. When he died, he owned extensive lands in four counties plus London.

His eldest son, Rowland, inherited Adlestrop and the lands around it in Gloucestershire (north of Oxford). His second son, Thomas, inherited Stoneleigh, Hamstall Ridware, and other estates in Staffordshire (north of Gloucestershire). The Adlestrop line remained country squires, while the Stoneleigh line gained a peerage by supporting Charles I in the English Civil War. They became far wealthier than the Adlestrop Leighs. By Jane Austen’s time, the Stoneleigh estate was worth around £17,000 a year, more than the income of wealthy Mr. Rushworth (£13,000) or Mr. Darcy (£10,000)!

I won’t inflict the whole family tree on you, as they repeated the same names over and over. Some of their favorite names were Thomas, Theophilus, James, Cassandra, and Mary. Cassandra Leigh Austen’s father was Rev. Thomas Leigh (1696-1764), and her mother’s maiden name was Jane Walker. Cassandra Leigh also had a sister named Jane, a sister-in-law named Jane, and, our favorite, a daughter named Jane (plus a daughter named Cassandra, and two first cousins named Cassandra). Jane Walker brought the Perrot family’s wealth into the family. [In the following, whenever I say “Cassandra Leigh” or “Cassandra Leigh Austen,” I mean our Jane Austen’s mother, not her sister.]

Adlestrop, Jane Austen, and the Clergy

Adlestrop is now best known for a poem written in 1914 by Edward Thomas, who died three years later in World War I. His train stopped there briefly, and the poem describes the natural beauties of the area, the “willows, willow-herb, and grass” and a blackbird singing. Adlestrop is still a small, rural town, as it was in Austen’s time.

The squire of the manor, Adlestrop Park, during Jane’s lifetime was James Henry Leigh, who inherited in 1774, when he was only nine years old. His uncle, Rev. Thomas Leigh, was his guardian and the rector of Adlestrop at that time. He was Cassandra Leigh’s first cousin. Rev. Thomas lived with his wife Mary and his unmarried sister Elizabeth, who was the godmother of Jane’s sister Cassandra.

Apparently Cassandra Leigh was closer to Rev. Thomas than to James Henry. On their visits, the Austens always stayed in the rectory, not in the great house. They would certainly have attended the Adlestrop church, where Rev. Thomas preached. Jane Austen first visited Adlestrop in 1794, when she was 19. She visited again five years later, in 1799, and then in 1806, when she was 31. Throughout the years, the Austen and Leigh families kept in touch through letters.

Many of Cassandra Leigh’s relatives were clergymen*, including her father, an uncle, two cousins, a brother-in-law, and a nephew. Leigh family members were patrons of various church livings connected with their extensive properties, and bestowed those livings on relatives, as was customary. In Austen’s novels, for example, both Henry Tilney and Edmund Bertram receive livings from their fathers. Livings might also be given by more distant relations. The Honorable Mary Leigh, for example, gave Edward Cooper (Jane Austen’s cousin) his living at Hamstall Ridware in Staffordshire.

Stoneleigh Abbey and Inheritance

In 1806, the last member of the Stoneleigh branch of the Leigh family, the Honorable Mary Leigh, died, and Rev. Thomas Leigh, inherited. Mrs. Austen [Cassandra Leigh, who was Rev. Thomas’s first cousin], with her daughters Jane and Cassandra, were visiting Rev. Thomas at the time, and they traveled with him to take possession of Stoneleigh. The Abbey made a strong impression on Jane and her family. Mrs. Austen wrote letters describing its wonders.

When Rev. Leigh inherited Stoneleigh Abbey, he gave a settlement to another claimant*, Jane’s uncle, James Leigh-Perrot (Cassandra Leigh’s brother). The understanding was that rich Mr. Leigh-Perrot would share this settlement with the needy Austens and Coopers. However, he did not. Jane attributed this lack of generosity to Mrs. Leigh-Perrot; perhaps she was caricatured as selfish Fanny Dashwood of Sense and Sensibility. You can find more details in “Jane Austen’s Leigh Family: Stories behind the Stories.”

When James Leigh-Perrot died, he left almost everything to his wife. Eventually, when Mrs. Leigh-Perrot died in 1836, some of her estate went to Jane’s nephew, James’s son James Edward. He had to take the name Leigh, becoming James Edward Austen-Leigh.

Next month I’ll post more pictures of Stoneleigh Abbey and talk about its possible parallels with Sotherton and Northanger Abbey in Austen’s novels.

Improvements—Mansfield Park

“Improvements” of land and property often meant providing more “picturesque,” more “natural” views, according to the ideas promoted by Gilpin at the time. In Mansfield Park, Mr. Rushworth wants to get the well-known expert, Humphry Repton, to improve his estate. Henry Crawford has already improved his own estate, and he advises Edmund Bertram on improving his parsonage. In Sense and Sensibility, Mrs. Dashwood talks often of making improvements to Barton Cottage, but she never has the funds for it. John and Fanny Dashwood do spend their money making improvements to Norland, which Elinor and Marianne don’t think much of. Mr. Collins makes improvements to his parsonage. Elizabeth is impressed that the Darcys have shown good taste in improving Pemberley, inside and out.

Austen more strongly commends personal “improvement,” though, improvement in mind, in manners, in education.

Austen would have known first-hand about Repton and his improvements from her cousins in Adlestrop and Stoneleigh. Rev. Thomas Leigh and his nephew employed Repton to make improvements to the manor, rectory, and surrounding lands of Adlestrop. Records show payments to Repton between 1798 and 1812.

Rev. Leigh “improved” his parsonage at Adlestrop by moving his front door to another side of the house, so the principal rooms would face the pretty valley. He also destroyed “a dirty farmyard and house which came within a few yards of the Windows.” Similarly, in Mansfield Park, Henry Crawford tells Edmund Bertram that he must improve his parsonage: “The farmyard must be cleared away entirely, and planted up to shut out the blacksmith’s shop. The house must be turned to front the east instead of the north—the entrance and principal rooms, I mean, must be on that side, where the view is really very pretty.” He also recommends combining gardens, changing a stream, and moving a road.

Rev. Thomas Leigh enclosed neighbouring land (with permission), adding it to his church living, and created a small lake from some flooded ground. As Huxley says, “Now he had a ‘Pleasure Ground’ to rival his brother’s” (at the Adlestrop estate). He moved roads and paths, as Mr. Knightley is planning to do in Emma. Jane Austen would have seen these improvements first hand during her visits. Sometimes she might have felt, like Mary Crawford, that all was “dirt and confusion, without a gravel walk to step on, or a bench fit for use” because of all the changes in process. However, as Mr. Collins did for his visitors, no doubt Rev. Leigh proudly took the Austen family on a thorough tour of his parsonage and its gardens, pointing out with pride all the improvements he was making.

In 1799, some land was exchanged between the church and the manor. In return, James Henry paid to build and fence a better church road and enclose the churchyard with a stone wall. In 1800, Repton was hired to unite the gardens of the rectory and Adlestrop Park, to improve the views. Dr. Grant in Mansfield Park also extends a wall and makes a plantation “to shut out the churchyard,” improving the view from the parsonage.

Austen would have heard about Repton’s later “improvements” in Stoneleigh Abbey’s grounds, which Thomas Leigh set about once he moved in. Repton’s “Red Book,” showing the suggested improvements, is still in existence. You can see a video of it here. Not all of Repton’s recommendations were followed, but some were.

The Leighs and Persuasion

Two other stories from the Leigh family are echoed in Persuasion. At one point, the Adlestrop family was deep in debt and needed to “retrench” in order not to lose the estate. They rented out the manor and moved to Holland for some years, until their finances were in order. Sir Walter and his family, of course, only moved to Bath; we wonder if they will ever make it back to Kellynch!

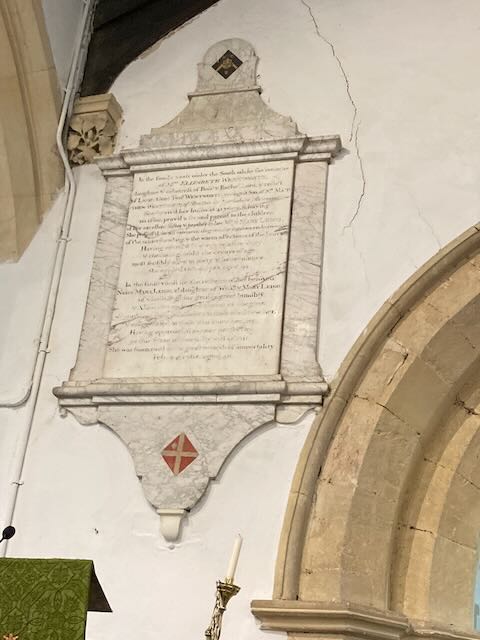

The Leighs also had an aunt who fell in love with an army officer. The family disapproved because of his lack of money. She married him secretly before he went off to war. When he returned as–guess who? Captain Wentworth!– she finally got her family’s approval. Elizabeth Wentworth and her Captain became wealthy and were benefactors to their Leigh relatives. The largest marble tablet in the Adlestrop church, just behind the pulpit, memorializes Elizabeth Wentworth.

For more of these stories, see my post on the Stories Behind the Stories.

Adlestrop Today

The church, St. Mary Magdalene, at Adlestrop is well worth a visit. The church dates from the thirteenth century, though much of it was rebuilt in the 1750s. In the Victorian period, the window traceries were replaced, and stained glass windows and a clock added. The church is one of seven in the Evenlode Vale Benefice. Services are usually held at St. Mary Magdalene twice a month. Like other country churches, a handful of the faithful attend regular services, while larger crowds come to special services at Harvest and Christmas. We don’t know about attendance numbers in Austen’s time. Supposedly, by 1851, “‘all parishioners without exception‘ attended church at least once a week” (Huxley, 201).

The rectory where Jane and her family stayed is now called Adlestrop House, and, along with Adlestrop Park, still belongs to the Leigh family. Both are very close to the church, but are not open to the public. The lands were originally monastic lands owned by Evesham Abbey.

The Old Schoolhouse opposite the church was built after Austen’s time. However, Austen probably saw the earlier charity school, supported by donations from the Leigh family and other local gentry. In 1803, sixteen children learned reading, knitting, and other marketable skills at that “school of industry.” By 1818 there was a day school for boys and another for girls. A Sunday school attended by 52 children was supported by a bequest from Rev. Thomas Leigh (Huxley, 203). (Sunday schools taught reading and other basic skills to working-class children, who were only free on Sundays.)

The last chapter of Jane Austen & Adlestrop takes readers on a tour of Adlestrop today, still a sleepy country village, but with history around every corner.

Notes

* Claimants for the Stoneleigh Abbey estate (this is complicated, sorry! You can find a chart of these relationships in Jane Austen & Adlestrop, by Victoria Huxley, or in Jane Austen and the Clergy, by Irene Collins):

Theophilus Leigh (died 1724), of the Adlestrop Leighs (great-great grandson of the Lord Mayor), had 14 children.

Theophilus’s oldest son, William, had a son named James (who died in 1774). James had one son (Theophilus’s grandson), James Henry (1765-1823). William’s second son was Rev. Thomas Leigh (1734-1813), rector of Adlestrop, who had no children.

Theophilus’s next surviving son, Dr. Theophilus Leigh (died 1785), was a clergyman and Master of Balliol at Oxford. He had no sons who survived childhood. One of his daughters married Rev. Thomas Leigh of Adlestrop, and another married Rev. Samuel Cooke, Jane Austen’s godfather.

Theophilus’s next son, also Rev. Thomas Leigh (died 1764), was Cassandra Leigh Austen’s father. He had a son, James Leigh-Perrot (1735-1817), just a year younger than Rev. Thomas Leigh of Adlestrop. James had added “Perrot” to his last name to get an inheritance from his wife’s family.

So in 1806, the closest living male heirs were Rev. Thomas Leigh of Adlestrop, who inherited the estate, then he passed it to his nephew James Henry Leigh. They gave money to James Leigh-Perrot, the third claimant, to pay off his claim.

For more stories of the Leigh family and their connections with Jane Austen’s novels, see “Jane Austen’s Leigh Family: Stories behind the Stories.”

Brenda S. Cox is the author of Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. She also blogs at Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.

Further Reading

“Jane Austen’s Leigh Family: Stories Behind the Stories”

“Jane Austen’s Clergymen and Her Leigh Family”

“Edward Cooper: Jane Austen’s Evangelical Cousin”

“Jane Austen’s Family Churches: St. Michael and All Angels, Hamstall Ridware”

Sources

Jane Austen & Adlestrop: Her Other Family, by Victoria Huxley. Highly recommended. US Amazon link

The Story of Elizabeth Wentworth or “Aunt Betty”—Jane Austen’s Anne Elliot? By Sheila Woolf (obtained from Stoneleigh Abbey)

Stoneleigh Abbey by Paula Cornwell (obtained from Stoneleigh Abbey)

Jane Austen: A Family Record, 2nd ed., by Deirdre Le Faye