…you want to hear about the wedding; and I shall be happy to tell you, for we all behaved charmingly.” –Emma

My husband and I were invited to a family wedding in England last June. The venue: Sherbourne Park, a Grade II Georgian house on a large estate dating back to 1730, just a few miles from Warwick and Stratford-upon-Avon. From the moment I first saw photos of Sherbourne Park, I felt a bit like a heroine in one of Jane Austen’s novels. I imagined myself walking the beautiful grounds, toasting the happy couple, and exploring as much of the house as possible.

You can imagine the added thrill I felt when I discovered we were also invited to stay the night at the “great house” after the wedding. My response was similar to that of Catherine Morland’s when she received her invitation to visit Northanger Abbey:

[Sherbourne Park]! These were thrilling words, and wound up [my] feelings to the highest point of ecstasy. [My] grateful and gratified heart could hardly restrain its expressions within the language of tolerable calmness. To receive so flattering an invitation! To have [my] company so warmly solicited! (NA 140)

With Sherbourne Park “on my lips,” I penned a quick “Yes!” on the reply card and began planning our trip.

Dressing the Part

As one of the “California relatives,” I certainly didn’t want to wear the wrong thing and open myself up to comments such as Mrs. Allen’s: “There goes a strange-looking woman! What an odd gown she has got on! How old-fashioned it is! Look at the back” (NA 23). Though I agree that a “woman can never be too fine while she is all in white” (MP 222), I knew I should leave that to the bride. Having “the greatest dislike to the idea of being over-trimmed” like Mrs. Elton, I decided that “a simple style of dress” would be “infinitely preferable to finery” (E 302).

My aim:

“nothing but what is perfectly proper” (MP 222).

The Question of Hats

Like Austen herself, I decided to wait until I arrived in England to “begin my operations on my hat, on which . . . my principal hopes of happiness depend[ed]” (Letters 17). Our English relatives assured us that many women would wear hats or fascinators. In Warwick, I found a small millinery shop filled with a variety of hats and fascinators. With the help of the capable shopkeeper, I found the perfect fascinator to match my gown. And unlike Lydia Bennet, I did not feel the need to “pull it to pieces” to see if I could “make it up any better” (PP 219).

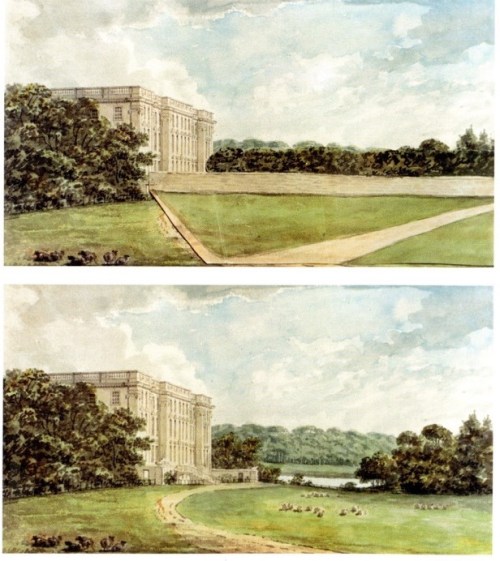

Sherbourne Park

The day of the wedding, we dressed in our finery and drove to Sherbourne Park, a 2,000-acre estate in Warwickshire. Tucked far back from the main road, the entrance was difficult to find, but at last we found the long, tree-line driveway. Much like Elizabeth Bennet, I “watched for the first appearance of [Sherbourne Park] with some perturbation” (PP 245). When “at length” we came out of the trees, my “spirits were in a high flutter.” I found that my mind was not “too full for conversation,” and I “saw and admired every remarkable spot and point of view,” exclaiming at every new sight. When I finally saw the house, I “felt that to be mistress of [Sherbourne Park, once upon a time] might be something!” (245).

The Church

The wedding ceremony was held in Sherbourne-All Saints Church of England, built in 1864, and was complete with Scripture readings and hymns on the organ. I wished to see if the bride had chosen to “put on a few ornaments,” since a “bride, you know, must appear like a bride” (E 302) and “longed to know if [the groom] would be married in his blue coat” (PP 319). The bride was as beautiful as could be and the groom was indeed in navy blue tails.

I found the “church spire . . . remarkably handsome” (MP 82).

However, unlike Maria Bertram, I was quite happy to find the church situated “so close the Great House,” only a short walk through the garden. I did not find the bells “annoying” at all! In fact, at the end of the service, as the newlyweds led the way out of the church, the church bells added much joy to the occasion. They continued for at least ten minutes and made a glorious clamor.

The Garden

The garden 1

The garden 2

The garden 3

Images of the gardens at Sherbourne Park by Rachel Dodge

A “taste for flowers is always desirable . . . as a means of getting [us] out of doors, and tempting [us] to more frequent exercise than [we] would otherwise take.” (NA 174)

Following the ceremony, we moved into the garden and gathered by the pool house for cocktails, appetizers, and ice cream. The garden at Sherbourne Park boasts beautiful flower beds, flowering trees and bushes, and many pretty paths to explore. “It was hot; and after walking some time over the gardens in a scattered, dispersed way, scarcely any three together” (E 360), we made our way toward the house and found “[s]eats tolerably in the shade” (359).

During the course of the afternoon, we heard that a member of the wedding party had actually fainted due to the warm weather. I thought perhaps someone should call for the local “Mr. Perry,” but another guest assured us that he “popped right back up” and we need not worry.

The Wedding Breakfast

[Y]ou shall all have a bowl of punch to make merry at her wedding.” (PP 307)

If Mr. Woodhouse couldn’t believe the “strange rumour in Highbury of all the little Perrys being seen with a slice of Mrs. Weston’s wedding-cake in their hands” (E 19), he could never have approved of the sublime variety (or amount) of food we enjoyed during the formal wedding breakfast. As we worked our way through multiple courses of delicious food and drink, a gentleman at our table leaned over and said, “It’s best to pace yourselves.” I took his advice and was quite happy with the results.

Though many of the mealtime formalities Jane Austen knew are no longer in use, I found one matter of wedding meal etiquette intriguing: During the wedding breakfast, all of the women kept their hats on. Later, after the speeches, the Mother of the Bride took off her hat, and the rest of the ladies in attendance followed suit.

The Great House

Interior of Sherborne Park. Image by Rachel Dodge

After an evening of dining and dancing, we entered the grand entrance hall of the great house with our luggage, found our rooms, and said goodnight. I thought of the description of Catherine Morland’s chamber in Northanger Abbey as I entered our room: “The walls were papered, the floor was carpeted; the windows were neither less perfect nor more dim than those of the drawing-room below; the furniture, though not of the latest fashion, was handsome and comfortable, and the air of the room altogether far from uncheerful” (NA 163).

Though I felt quite at ease sleeping there, I later found out that my sister-in-law felt a bit more like Catherine as she tried to fall asleep in the dark, creaking old house.

In the morning, we came downstairs to tea and toast in the large, formal dining room. Again, I was reminded of the descriptions in Northanger Abbey: Sherbourne Park’s

“dining-parlour was a noble room [. . .] fitted up in a style of luxury and expense” (NA 165-6).

While we were eating, the current owner of Sherbourne Park, Robin Smith-Ryland, came down from his residence upstairs and told us about the history of the estate. The Ryland family has held it for over 200 years, and they now run the house and grounds as a venue for corporate events, weddings, and hunting/fishing outings. Smith-Ryland gave us a tour of the house, which can accommodate up to 15 guests. The drawing room, morning room, open fireplaces, and multiple bedrooms were laid out most invitingly.

After brunch in the garden, we moved into the drawing-room to visit with our relatives and enjoy the aftermath of the wedding day. Alas, later in the morning, we packed our things and began to say our goodbyes. We waved as “the bride and bridegroom set off . . . and everybody had as much to say, or to hear, on the subject as usual” (PP 146).

All in all, it was a beautiful wedding weekend. The best part truly was spending the long weekend with my family. I can only hope that we’ll be invited back for the bride’s younger brother’s wedding one day because as we all know, “the expectation of one wedding” always makes “everybody eager for another” (PP 360).

You can follow Rachel Dodge at www.racheldodge.com or on Twitter, Instagram (@kindredspiritbooks), or Facebook.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane, and R. W. Chapman. The Oxford Illustrated Jane Austen. Oxford UP, 1988.

Austen, Jane. Jane Austen’s Letters. Edited by Deirdre Le Faye, 4th ed., Oxford UP, 2011.

Read Full Post »