By Brenda S. Cox

“Immediately surrounding Mrs. Musgrove were the little Harvilles, whom she was sedulously guarding from the tyranny of the two children from the Cottage, expressly arrived to amuse them. On one side was a table, occupied by some chattering girls, cutting up silk and gold paper; and on the other were tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies, where riotous boys were holding high revel; the whole completed by a roaring Christmas fire, which seemed determined to be heard, in spite of all the noise of the others. . . .

Mrs. Musgrove . . . observ[ed] with a happy glance round the room, that after all she had gone through, nothing was so likely to do her good as a little quiet cheerfulness at home. . . .

” ‘I hope I shall remember, in future,’ said Lady Russell, as soon as they were reseated in the carriage, ‘not to call at Uppercross in the Christmas holidays.’ Every body has their taste in noises as well as in other matters . . .”—Persuasion, Vol. 2, chapter 2

Jane Austen gives us only brief glimpses of Christmas in her world. Here Mrs. Musgrove and Lady Russell think very differently about what makes a pleasant Christmas. The Musgrove family are enjoying crafts, food, a Christmas fire, and children having fun and making noise.

Family and Friends

At Christmas, people gathered with friends and family, as we still do today. In Northanger Abbey, Catherine’s brother James met Isabella Thorpe when he went to spend the Christmas holidays with Isabella’s brother. In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth invites the Gardiners to join her and Darcy at Pemberley for Christmas. In Sense and Sensibility, Charlotte Palmer asks the Dashwood sisters to join her at Cleveland for Christmas.

In Emma, Emma’s sister and her husband come to visit for the holidays with their children. They are busy with friends during the mornings, and Mr. Weston insists that they dine with him one eventful evening.

Mr. Elton, at least, enjoys the occasion, saying:

“This is quite the season indeed for friendly meetings. At Christmas every body invites their friends about them, and people think little of even the worst weather. I was snowed up at a friend’s house once for a week. Nothing could be pleasanter. I went for only one night, and could not get away till that very day se’nnight.”—Emma, chapter 13

Mr. Elton drinks too much and proposes to Emma, who rejects him. She is therefore very glad on Christmas day to see

“a very great deal of snow on the ground. . . .The weather was most favourable for her; though Christmas Day, she could not go to church.”—Emma, chapter 16

The snow could be dangerous. And certainly Mr. Woodhouse would find it so.

Church on Christmas Day

The clear implication, though, is that Emma would naturally have gone to church on Christmas day. Churches generally had a good turn-out on Christmas. Communion was generally offered that day (one of only three or four times a year when country churches would offer Communion, also called the Lord’s Supper). Henry Crawford in Mansfield Park assumes that Edmund Bertram will only need to preach on the major holidays when many people attended church:

“A sermon at Christmas and Easter, I suppose, will be the sum total of sacrifice.”— Mansfield Park, chapter 23

Edmund, of course, plans to live in his parish and lead services and preach there every Sunday, not just on holidays.

For each church holiday, the Book of Common Prayer, handbook of the Church of England, prescribed specific prayers and Bible readings that would be the same every year. The “collect” prayer from the 1790 Book of Common Prayer for “the Nativity of our Lord, or the birth day of CHRIST, commonly called Christmas-day” is:

“Almighty God, who hast given us thy only begotten Son to take our nature upon him, and as at this time to be born of a pure Virgin; grant that we being regenerate, and made thy children by adoption and grace, may daily be renewed by thy Holy Spirit, through the same our Lord Jesus Christ, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the same Spirit, ever one God, world without end. Amen.”

Bible readings for the day were from the first chapter of the book of Hebrews and the first chapter of the book of John, both about the coming of Christ.

In a recent talk by Rachel and Andrew Knowles on “A Regency Christmas,” they pointed out that Christmas day, and the whole Christmas season, was a popular time for weddings in the churches. So perhaps that was Austen’s little joke, having Mr. Elton propose right before Christmas! Babies were also christened on that day, and Christmas was a time for ordaining new clergymen. Edmund Bertram goes to Peterborough for ordination during Christmas week. When he delays his return, Mary Crawford thinks he may be staying for “Christmas gaieties.”

Christmas Gaieties

Miss Bingley uses the same term when she writes to Jane Bennet:

“I sincerely hope your Christmas in Hertfordshire may abound in the gaieties which that season generally brings, and that your beaux will be so numerous as to prevent your feeling the loss of the three of whom we shall deprive you.”—Pride and Prejudice, chapter 21

What did those gaieties involve?

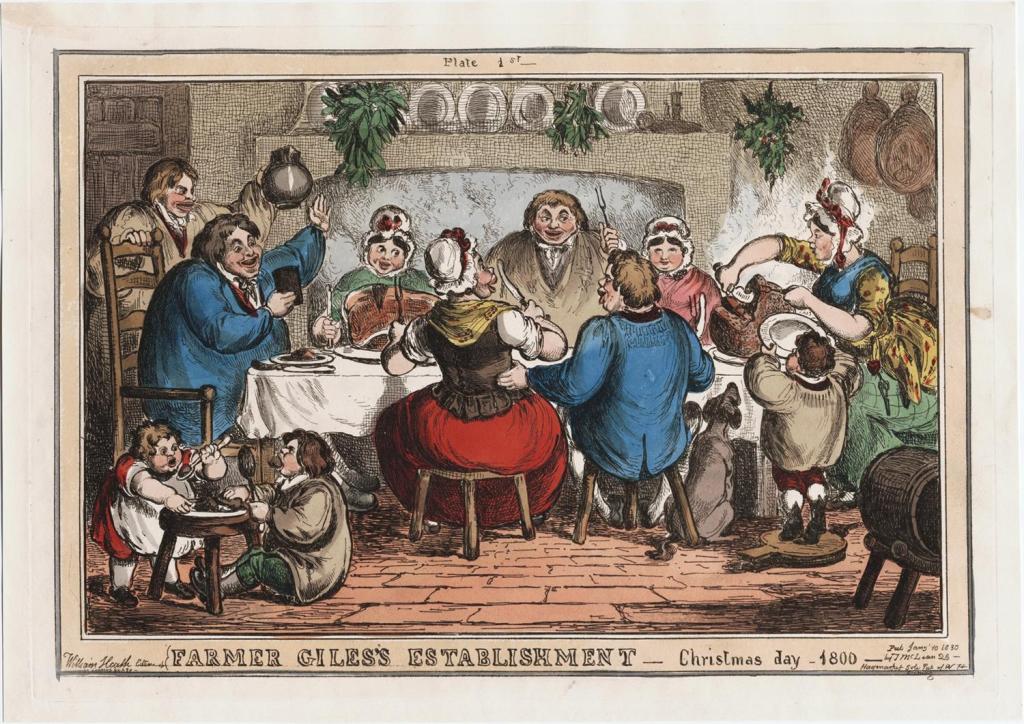

Customs that were consistent across the country were gathering with family and friends, eating a special meal, and giving gifts and money to the poor. Austen mentions a few additional traditions.

Farmer Giles’s Establishment, Christmas day, 1800, by William Heath, 1830. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Gifts

Christmas was a time for charity, for giving gifts to the poor and to those in service occupations, like the local butcher. These gifts of money were called “Christmas boxes.” According to the Knowles’s research, newspapers even published lists of what certain wealthy people were giving to the poor at Christmas.

In families, it appears that gifts were given mainly to children. I found only one mention in Austen:

“On the following Monday, Mrs. Bennet had the pleasure of receiving her brother and his wife, who came as usual to spend the Christmas at Longbourn. . . . The first part of Mrs. Gardiner’s business on her arrival was to distribute her presents and describe the newest fashions. . . . The Gardiners stayed a week at Longbourn; and what with the Phillipses, the Lucases, and the officers, there was not a day without its engagement. Mrs. Bennet had so carefully provided for the entertainment of her brother and sister, that they did not once sit down to a family dinner.”—Pride and Prejudice, chapter 25

It’s not clear if Mrs. Gardiner brought gifts for everyone because it was Christmas, or if she was just bringing gifts because she was coming from London to the country on a visit.

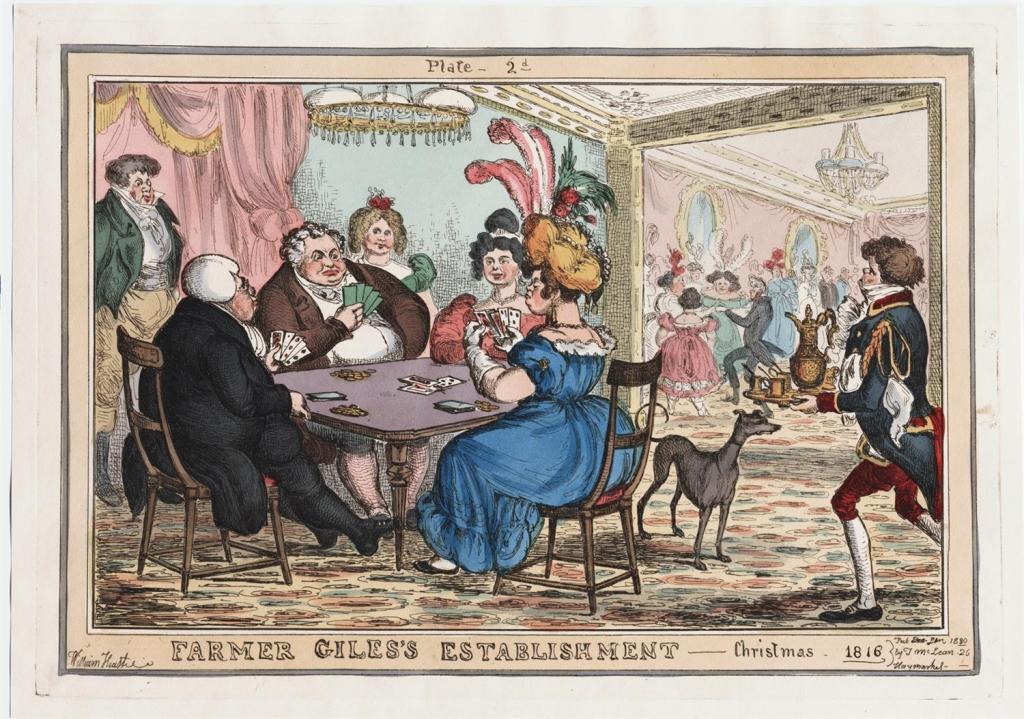

Games

Many played games at Christmastime. Jane Austen wrote in a letter to Cassandra from Portsmouth, on Jan. 17, 1809 about a change in the fashions for Christmas games:

“I have just received some verses in an unknown hand, and am desired to forward them to my nephew Edward at Godmersham:

Alas! poor Brag, thou boastful game! What now avails thine empty name?

Where now thy more distinguished fame? My day is o’er, and thine the same,

For thou, like me, art thrown aside At Godmersham, this Christmas tide;

And now across the table wide Each game save brag or spec. is tried.

Such is the mild ejaculation Of tender-hearted speculation.”

Farmer Giles’s Establishment Christmas 1816 by William Heath, 1830. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Dancing

Austen’s characters dance at Christmastime. Sir Thomas Bertram holds a ball for Fanny Price during the Christmas holidays. Sir John Middleton hosts a Christmas dance, followed by a hunt the next morning:

“‘He [Willoughby] is as good a sort of fellow, I believe, as ever lived,’ repeated Sir John. ‘I remember last Christmas at a little hop at the park, he danced from eight o’clock till four, without once sitting down.’

“‘Did he indeed?’ cried Marianne with sparkling eyes, ‘and with elegance, with spirit?’

“‘Yes; and he was up again at eight to ride to covert.’”—Sense and Sensibility, chapter 9

Other Christmas Traditions

According to the Knowles, Christmas customs were different between city and country, and between various areas of the country. In some areas old customs like the Yule log and decorating with greenery were dying out, in other areas they were still going strong.

Whatever traditions your family keeps during this holiday season, may you experience much joy and deep peace.

If you want to find out more about specific Christmas customs in Austen’s England, check out any of these posts:

Regency Christmas Celebrations answers many questions about Christmas in Austen’s time, and links to posts on Father Christmas and on Christmas trees.

Christmas Carols and Christmas Carols of Yore

Regency Christmas Tree (with links to other Christmas articles)