Inquiring readers,

I recently moved and, like Jane, left a home I loved. When I purchased my current slice of paradise, I found my perfect place. In addition, my new neighborhood suits my personality. Echoes of Jane Austen in Chawton Cottage!

Rachel Dodge, who writes splendid articles for this blog, wrote a wonderful post last year about moving entitled Jane Austen’s Tips on Moving House. I cannot improve on her article. I can, however, discuss the various 18th C. methods by which the English moved their possessions – large or small.

Thomas Rowlandson: A Posting Inn, 1787, Met Museum, public domain image

This print shows three vehicles beside an inn – two moving, one parked:

- The parked vehicle is a public coach laden with passengers and drawn by four horses. The animals are being switched out for a fresh team, which, depending on the size, weight, and speed of the coach occurs every 6 – 12 hours. Switches slowed the journey’s progress and provided passengers with an opportunity to disembark and look to their personal needs. Some might choose to spend the night or enjoy a meal at the inn, much like Lydia, Kitty, Jane and Elizabeth.

“…in Hertfordshire; and, as they drew near the appointed inn where Mr. Bennet’s carriage was to meet them, they quickly perceived, in token of the coachman’s punctuality, both Kitty and Lydia looking out of a dining-room up stairs. These two girls had been above an hour in the place, happily employed in visiting an opposite milliner, watching the sentinel on guard, and dressing a salad and cucumber.” – Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 13

After welcoming their sisters, the girls triumphantly displayed a table set out with such cold meat as an inn larder usually offers, exclaiming, “Is not this nice? Is not this an agreeable surprise?” Elizabeth and Jane remained calm and collected, and murmured approval in the appropriate way. Silently Lizzie (and we readers) thought Lydia and Kitty the silliest of chits.

The Dashwood women took a public coach out of necessity after vacating Norland Park with just enough funds to live as gentlewomen in a cottage provided generously by Mrs Jenkins, a relative stranger to them.

The above image depicts the Dashwood women leaving the carriage and seeing Barton Cottage for the first time. Notice the luggage strapped on top of the conveyance. Their furniture, cutlery, tableware, linens and the like would most likely be delivered in a humble wagon by a male servant before or after the move. Servants were often sent ahead of time to ready the new dwelling or they might travel at the same time in a different carriage or wagon.

Passengers sitting inside a crowded carriage carried their possessions on their laps or between their feet, especially those unfortunate enough to sit in the middle. Those sitting on top were subject to the elements, come rain or snow.

2. In the center of the print is a post chaise that is often a private carriage. It could seat from two to three passengers and was guided by a postillion astride one of two or four horses. A trunk placed in the front of the carriage and behind the horses was just big enough to carry personal effects. This private carriage was more expensive to hire than a public coach, for the vehicle’s speed was highly prized, especially by couples who eloped to Gretna Green.

3. The vehicle to the left is a humble cart pulled by a pony or donkey. Austen’s donkey carriage, also known as a donkey cart, looks elegant in comparison. (See image in link.) After a cold spell in January of 1817, Jane wrote:

‘our Donkeys are necessarily having so long a run of luxurious idleness that I suppose we shall find that they have forgotten much of their Education when we use them again.’

Austen used the vehicle for local shopping runs to Alton. The vehicle depicted by Rowlandson provided little space for purchased goods. These carts were serviceable for moving a few possessions to a location not far away and for individuals who could make frequent back and forth trips. Austen drove her cart at the breakneck speed of 4 mph in her travels to Alton, a trip that took 20 minutes one way.

Along the road:

Before the railroads were built, beasts of burden were the “engines” used for transport on land and along man-made canals. They included horses, oxen, mules, and donkeys. Small carts were often pulled by goats or large dogs. As mentioned before, all needed food, water, shelter, and rest, an expense that poor owners could barely afford. Animals who did not receive these basic necessities, lived shortened lives. Often a beast of burden’s reward after years of service was either a trip to the knacker after it died or to a farmer to labor until they dropped from exhaustion.

A Dead Horse on a Knacker’s Cart. Thomas Rowlandson, Wikipedia

Even with the help of beasts of burden, moving heavy furniture and a large quantity of personal possessions was no small feat. The pace of travel was slow and often laborious. Before roads were macadamized in the early 19th century, they were in poor condition. After heavy rains, deep ruts and mud slowed vehicles down. Winter snow and ice presented additional hazards. Animals as well as passengers and drivers suffered the most in these harsh elements.

Working animals’ lives were even more drastically reduced from their exertions of pulling heavy wagons and over loaded carriages. Mail coaches during Austen’s day were the fastest means of land transportation. A faster speed was achieved by driving the horses at top speed and changing the teams every 12 to 15 miles or about every 2 hours. These horses, urged to attain maximum speed at whatever cost, had drastically shortened working lives and lifespans.

The images below show the challenges of moving heavy wagons in snow and mud. Click on the images to enlarge.

The liverpool mail near St Albans – Robert Havell (click the link to see image, which is copyrighted. Horses are stopped with its leader fallen.)

Types of vehicles and those who used them:

Travel for the upper classes:

Income determined the conveyance in which an individual or family moved and how many household goods could be transported over a certain distance. Aristocrats and rich landowners, like Mr Darcy, experienced few impediments. The rising middle classes could also choose more comfortable and efficient means of travel. One can imagine that Mr Bingley arrived at a fully furnished Netherfield Park, having sent trusted representatives and servants ahead of time to see to the details of moving personal belongings, and hiring competent locals to perform additional labor. Keep in mind that the upper crust travelled in style, while servants, aside from valets and ladies maids, accompanied their masters’ possessions in less desirable transportation.

- For more visual references regarding carriages for the upper classes, Deborah Barnum of Jane Austen in Vermont offers valuable posts on the topic. Click on this link: IV of a series.

Landless gentry and aspiring social climbers make do with less elegant equipages:

Mrs Elton, a ridiculous character in Austen’s splendid novel, Emma, assumes that her social position in Highbury is equal to Emma’s. Austen has fun with the character, who utters one absurd opinion after another. She piggy backs onto her sister’s wealth by bragging about that woman’s elegant carriage, while expressing a desire to Mr Knightley to have a donkey. He wryly suggests that she could borrow Mrs Cole’s animal, implying she could save herself the money. In reality, the Eltons must make do with what they have.

Crofts arrive in a gig, Persuasion 1995. Gigs were not associated with the rich, and the Crofts drove theirs for local excursions only.

“She and her husband are provided with an unexceptionable carriage and horses that suffice for their needs, though of course they cannot be compared with her wealthy sister’s equipage, a barouche-landau….” – Diana Birchall quote in writer Sarah Elmsley‘s splendid blog.

Mr Elton, a mere vicar, served parishioners at a lower social scale than Rev Austen. While Elton received a salary and a rent-free a house, he received no tithes, which limited his income and necessitated his finding a wife with resources. He overstepped his ambition by wooing Emma Woodhouse, but settled for Augusta Elton, whose connections are murky. His marriage to Augusta increased the readers’ enjoyment of the couple’s absurdities.

Austen’s father, Rev George Austen, enjoyed an income from a variety of sources, including a 10% tithe from parishioners from two parishes who could afford to pay the amount. He also oversaw a glebe land, which he farmed. This combined income should have served him well, but his large family necessitated that he and Mrs Austen run a boy’s boarding school for profit inside Steventon Rectory. When George retired, his son James inherited his living and the house the family once occupied, but Rev Austen retained the income from the tithes of the parishes he once served. When he died, this income ceased, plunging the Austen women into financial difficulties, which resulted in their continual quest to find more affordable lodgings — until Edward Austen Knight offered Chawton Cottage to them. This last move resulted in Jane Austen’s glorious creative period in which she published five novels during her lifetime.

Rev Austen and his family moved to Bath in 1801, with only the possessions that would fit into their new home. He no longer had his extensive library or the use of a horse and carriage. The family’s many servants were reduced to a cook, manservant, and one or two maids, depending on the family’s needs. Like other families in their economic situation, they used hired carriages, such as hackney coaches, or public coaches to reach destinations beyond walking distance. During the family’s move to Bath, the goods and possessions they could not physically take with them were most likely transported by a manservant in a wagon.

Hackney Coach 1800

The 60-mile journey from Steventon to Bath took one day. A rest for the horses at an inn or hotel like the Petty France was a necessity. The following quote from Dean Cantrell describes Catherine Morland’s journey from Bath to Northanger Abbey. The Austen family must have also shared the same feelings:

“Both carriages stop at Petty France, exactly half the thirty-mile distance from Bath to the General’s Abbey. Catherine laments “the tediousness of a two hours’ bait” that permits “nothing to be done but to eat without being hungry, and loiter about without any thing to see” (NA, 156). She clearly understands that it is the chaise with its “heavy and troublesome business” that requires a two-hour halt for the horses to be fed and refreshed…Fifteen miles from Bath, Petty France would have been a likely coach stop in 1801 and 1806 for Jane Austen.” – Yes, There is a Petty France, Dean Cantrell, Persuasions, 1987

Petty France Hotel

A sixty mile journey must have been exhausting in a public conveyance. View more images of public transportation in this Jane Austen in Vermont, post number III.

People from humbler walks of life and their forms of transport:

Three Rowlandson images of a flying wagon speak volumes on how people with modest means traveled and transported their goods in wagons that look remarkably like the Conestoga wagons colonists drove across America.

Rowlandson, Flying Wagon, MET Museum, public domain, 1816

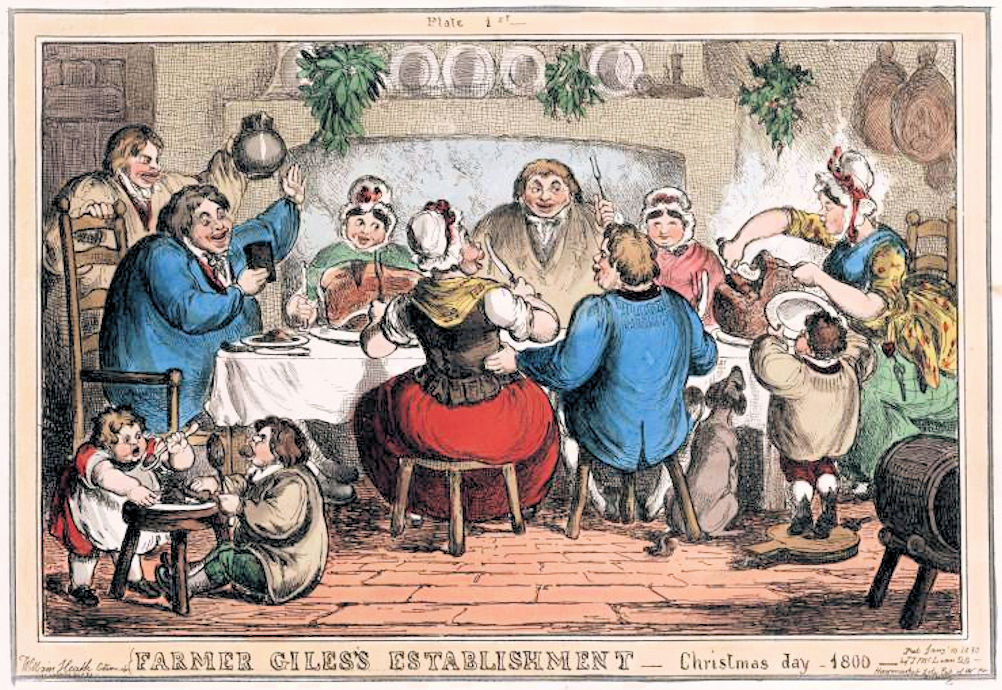

This Kendal Flying Machine, a wagon, is parked outside of an inn. A woman climbs up a ladder into the wagon. Three men stand at right. In Mr. Rowlandson’s England, Robert Southey described the laboriously slow progress of a flying wagon:

The English mode of travelling is excellently adapted for every thing, except for seeing the country…We met a stage-waggon, the vehicle in which baggage is transported, I could not imagine what this could be; a huge carriage upon four wheels of prodigious breadth, very wide and very long, and arched over with a cloth like a bower, at a considerable height: this monstrous machine was drawn by six large horses, whose neck-bells were heard far off as they approached; the carrier walked beside them, with a long whip upon his shoulder…these waggons are day and night upon their way, and are oddly enough called flying waggons, though of all machines they travel the slowest, slower than even a travelling funeral.” – P 23

From Southey’s description and depiction of the flying wagon in the first Rowlandson image, one can see the differences in size and the numbers of people and the size of the loads each of these wagons could carry. Rowlandson’s first image of a flying waggon depicted a much smaller vehicle than the one shown in the rendering on P 23, which was drawn by six horses.

The detail below of an 1806 Dutch etching from The Rijksmuseum shows a cart laden with furniture moving through a small village. A man walking in front seems to be carrying baskets with items inside.

As in the illustration above, affordable modes of transportation of two- or four-wheel uncovered wagons, were used by humbler people who could afford them. Examples are included in the slide show below. Notice that some images are current, since the mode of moving goods among the poor has changed little over the centuries.

Detail of pack horses.

Very poor or itinerants who moved from place to place often walked, carried their personal goods in sacks, pushed them in wheelbarrows or hand carts, rode pack horses, or caught a ride by a kind stranger.

Rivers and inland waterways:

Overland transportation was not the only route people took to move to a new location. England’s streams and rivers had long been a fast, efficient means of travel.

Steam locomotives arrived 3 years before Jane Austen’s death. Before this time, transport via inland waterways and rivers provided a more comfortable and, in many instances, a faster way to move items. Ferries took people and wagons across river crossings.

A surge in canals building occurred in England in the second half of the 18th century, and by the mid-19th century these canals helped the expansion of the English Industrial Revolution. In Jane Austen’s day, most developers still struggled to make a profit building canals. Once they were introduced to connect city to city and routes within cities, these canals became an important source of transporting goods within England and were more profitable.

Horse drawing from a towpath on the Kennet and Avon Canal, England, Wikipedia

“A horse, towing a boat with a rope from the towpath, could pull fifty times as much cargo as it could pull in a cart or wagon on roads. In the early days of the Canal Age, from about 1740, all boats and barges were towed by horse, mule, hinny, pony or sometimes a pair of donkeys.” Wikipedia, Horse-drawn boat

Importantly, ferries, canal boats, and barges carried heavier loads: they also provided accessibility and affordability to a variety of people from different classes.

Seaside ports:

Another popular means of transportation in England, an island nation, was via ships that sailed along and around its coastlines to various coastal ports and into major cities.

A View of London Bridge and Custom House, Robert Havell, Sr., Yale Center for British Art

Additional information on the topic:

- History of Canals in Great Britain https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryMagazine/DestinationsUK/The-Canals-of-Britain/

- Why the Way One Traveled Was Important in Austen’s Time

- British Waterways and Canals: History and Narrowboats

- An Insider’s Guide to the History of Barges by European Waterways

- The Evolution of the Narrow Boat – Inland Waterways

- 18th Century Goods Transport | Learning with London Canal Museum

- The Difficulties of Travel and Transportation in Early 19th C. Britain | Jane Austen’s World